![]()

1

Smoke that Means the Entire World

How to start? That is an agonizing question that often occupies the mind of a struggling writer. There are different kinds of starts. One of them is the first sentence in a printed book. An Auster book can start with a misleading phone call, as in City of Glass: “It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night …” The first sight might be more dramatic: a man blowing himself to pieces (Leviathan), a man walking on the water (Mr. Vertigo). That opening sentence can affirm life (“One day there is life,” The Invention of Solitude), suspect death (“Everyone thought he was dead,” The Book of Illusions), or acknowledge the presence of both (“I had been sick for a long time,” Oracle Night). The book can start with the end: “These are the last things, she wrote. One by one they disappear and never come back” (In the Country of Last Things).1

But where does an author’s oeuvre start? There are no such first sentences. The first sentence of a published book? Paul Auster published his first book, Squeeze Play, back in 1982 under a pseudonym (Paul Benjamin). Does it necessarily have to start with a book? What about a published article, an essay, a poem or a translation? “How can we enter into Kafka’s work?”, Deleuze and Guattari ask rhetorically as they embark on their study of Franz Kafka, a writer to whom Auster has often been compared. “The castle has multiple entrances whose rules of usage and whose locations aren’t very well known,” they write, referring to Kafka’s novel The Castle.2 After all, in such textual rhizomes, every entrance point has the same value: “none matters more than another,” and “no entrance is more privileged.”3 Eco, too, has said that “[t]he main feature of a net is that every point can be connected with every other point, and, where connections are not yet designed, they are, however, conceivable and designable. A net is an unlimited territory … The abstract model of a net has neither a center nor an outside.”4 Or else (and this is Auster speaking): “the center is everywhere. Every sentence of the book is the center of the book.”5

There can be many starts—we know that—and no finite end points. But some of the starts are false, illusory. Some entrances are too narrow, and their gates quickly lead to a dead-end. An Auster intratext cannot be entered through an image of withering flowers on a balcony in a Tuscany villa, or the song of cranes gathering in wetlands before their autumn migration. These elements (flowers, cranes) are like foreign molecules that, when colliding with Auster’s body of work, instead of interacting with it merely bounce off. This collision does not result in a chemical reaction. Some doors simply do not lead anywhere.

Others, however, open up worlds of possible trajectories. That is suggested by the piles of research material that I have gathered on my desk as evidence: entire collections of textual particles that, within this particular author’s body of work, seem to always interact with one another, transform, connect, multiply, flourish. Nouns dominate there—things, and spaces and ideas—and there are only very few adjectives, such as “lost” or “empty.” If all these elements were written down, we would get an infinite book, a never-ending scroll. But this list would be more than a glossary of Paul Auster. It would conjure up an entire diegetic universe that is open and overlapping with other universes, and yet also so uniquely Austeresque that you would unmistakably recognize it as inhabited by this writer. Together, these particles work to form Auster texts, from small mises en scène to entire plots.

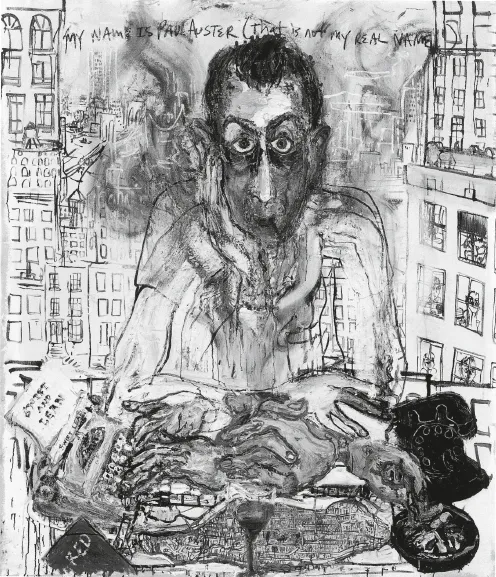

What things are most Auster-like? Things that are both concrete and abstruse—like the meta-mind of Auster’s writer-character that always wants to ponder the relationship between the external (the physical body, the world) and the internal (the mind, the imaginary) in an eternal loop of the Möbius Strip. Or, like a cigarette, this tiny harmful object whose pungent fumes nevertheless contain creative forces so powerful that I can confidently say: Paul Auster’s texts are written by cigarettes—first written, and then obscured by the accompanying clouds of smoke. And, as I am sitting here in my study, smoking, and contemplating the numerous portraits of Auster’s smoking characters that I have pinned up to the wall in front of me, it seems to me that cigarettes and smoke make a good starting point for entering his work. It is not only because they are ever-present tools of writing that are intrinsically linked with the process of artistic creation. It is also because of the inherent contradiction they exhibit. It seems to “rhyme” with the paradoxical nature of Auster’s life-work itself.

“Smoke is something that is never fixed, that is constantly changing shape.”6 Paul Auster used these words to comment on the title of his film Smoke and to describe the kind of relationships between the characters, who “keep changing as their lives intersect.”7 Yet these words are more than an allegorical comment on the intangible and dynamic quality of human relationships. The metaphor of tobacco smoke is one of the central elements in Auster’s meta-story, and its changing symbolism reveals the multilayered and inconsistent texture of both his characters and texts. And, as I recall the pleasure that Quinn from City of Glass takes in smoking as he blows the smoke into the room and watches it “leave his mouth in gusts, disperse, and take on new definition as the light caught it,”8 I sense that the ritual of smoking is not unlike Auster’s text-creating ritual, where the same ideas, the same substances, leave the author’s mind to take on a new form and definition.

In some contexts, the significance of tobacco expands beyond its purely metaphorical dimensions, becoming an active agent in the process of constituting Auster’s universe. Rather than a passive and inanimate object, tobacco appears as a living element, which, like the manual typewriter, is always present in his work, although with changing moods and meanings. Like the typewriter (which I suspect to be haunted), cigarettes, too, are capable of talking to the writer and channeling inspiration. The cigarette is that thing that opens up the space where the interior of the book (or the writer’s mind) merges with and leaks out into the exterior of the world. It is the door that opens up the realm of the imaginary. Its function as such is not unlike that of the writer’s bare room in which he produces his often solipsistic texts.

In the Heideggerian sense, tobacco in Auster’s texts is the thing that “things.” In order to understand how exactly tobacco and smoking “acts” in Auster’s polyphonic texts, one has to “follow the actors themselves,” as Latour would say, to see what kind of associations they establish, and how they work to make these textual networks fit together.9 We have to look into the “metaphorical potencies”10 of tobacco, and the work they do in assembling certain concepts, ideas and relationships. If there is an interpretive plurality characterizing Auster’s films Smoke and Blue in the Face (two texts literally wrapped in clouds of tobacco smoke), that is also because of the different possible ways in which we can read “smoking.” Because the cigarette has what Eco calls a “plurifilmic personality,” the texts which it helps to assemble and within which it acts also acquire a “plurifilmic” quality.11 This potential for parallel, multilayered readings of the metaphor of smoke and of Auster’s texts reminds us that, rather than having one fixed meaning, “the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, ‘and … and … and …’.”

How can I introduce this small cylindrical object, this thing—the cigarette—which in Richard Klein’s words turns out to be “bigger than life”?12 For Klein, cigarettes are especially ambiguous signs which are difficult to read, and the difficulty is related to “the multiplicity of meanings and intentions that cigarettes bespeak and betray” as they “speak in volumes.”13 The cigarette is itself “a volume, a book or scroll” that “unfolds its multiple, heterogeneous, disparate associations around the central governing line of a generally murderous intrigue.”14 This thing is a multilayered text that wants to be read and decoded. One wants to disperse that smoke that surrounds it and that appears to be hiding a hermeneutical secret.

The following passages from Cigarettes are Sublime, Klein’s book that itself has a dual function as both an elegy and an ode to smoking, sums up the impossibility of capturing the contradictory essence and trickster-like nature of the cigarette. Its laconic form, visual simplicity and “whiteness” deceptively hide complexities of meaning:

One has difficulty asking the question, the Aristotelian philosophical question, ‘Ti estin [What is] a cigarette?’ The cigarette seems, by nature, to be so ancillary, so insignificant and inessential, so trifling and disparaged, that it hardly has any proper identity or nature, any function or role of its own—it is at most a vanishing being, one least likely to acquire the status of a cultural artifact, of a poised, positioned thing in the world, deserving of being interrogated, philosophically, as to its being. The cigarette not only has little being of its own, it is hardly ever singular, rather always myriad, multiple, proliferating. Every single cigarette numerically implies all the other cigarettes, exactly alike, that the smoker consumes in series; each cigarette immediately calls forth its inevitable successor and rejoins the preceding one in a chain of smoking more fervently forged than that of any other form of tobacco.

Cigarettes, in fact, may never be what they appear to be, may always have their identity and their function elsewhere than where they appear—always requiring interpretation. In that respect they are like all signs, whose intelligible meanings are elsewhere than their sensible, material embodiment: the path through the forest is signaled by the cross on the tree.15

Yet nothing perhaps sums up its nature better than the statement that the cigarette and smoking always imply a certain paradox that Klein sees epitomized by Zeno Cosino’s life-long attempt to quit smoking in Italo Svevo’s 1923 masterpiece La coscienza di Zeno, or Zeno’s Conscience.16 The determination to give up cigarettes and the never-ending succession of repetitions of the same resolution to stop smoking become not only a lifestyle for Zeno but also what defines him as a smoker. Not wanting cigarettes becomes a major pretext for continuously smoking the “last” cigarette, a paradox encapsulated by Klein in the sentences below and illustrated by Jim Jarmusch’s smoking character in an episode in Auster’s film Blue in the Face. (There, Jarmusch’s “Bob” is sharing the moment of smoking his “last” cigarette with Harvey Keitel’s character Auggie.) Klein on the paradox:

To stop, one first has to smoke the last cigarette, but the last one is yet another one. Stopping therefore means continuing to smoke. The whole paradox is here: Cigarettes are bad for me, therefore I will stop. Promising to stop creates enormous unease. I smoke the last cigarette as if I were fulfilling a vow. The vow is therefore fulfilled and the uneasiness it causes vanishes; hence the last cigarette allows me to smoke many others after that.17 (his emphasis)

This unsolvable contradiction is inherent in the double nature of the cigarettes, which makes them appear so desirable because they are so deathly. You would agree with me that the pleasure itself that the cigarettes offer, strictly speaking, is not really pleasure. Cigarettes stink, they burn your throat, and you surely would not smoke them for the taste. Of all the “pleasure goods” that were introduced to the European society at the dawn of the modern age—coffee, or chocolate, or sweet spices—tobacco, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch writes, is “undoubtedly the most bizarre.”18 Cigarettes are simultaneously bad and good, beautiful and ugly, tasty and repulsive, adored and hated, associated with the sacred and the demonic. The dual nature of the cigarette expresses itself also in terms of the physiological and psychological effects of smoking that vary according to the different conditions in which cigarettes are consumed: to calm and to excite, to numb the senses and to intensify them, to remember and to forget, to celebrate and to mourn, to pull yourself together and to let go of yourself.

Nick Tosches’ description of the city of Las Vegas as “a religion, a disease, a nightmare, a paradise for the misbegotten” could be equally attributed to smoking.19 Klein concludes that “[n]othing … is simple where cigarettes are concerned” because “they are in multiple respects contradictorily double.”20 Cigarettes are like doppelgängers, which also proliferate in the work of Auster, for whom, I think, both become “a way to express [his] contradictions” via “paradoxical shuttling” between two opposite ends.21 This tolerance of inner contradiction that characterizes the cigarette is one of the reasons why Paul Auster’s life-work, which has the same inherently “inconsistent” quality, is full of characters who are essentially smokers. To light a cigarette means to embrace a paradox.

It is difficult for me to visualize the Brooklyn writer Paul Auster without his low, smoky voice and the always-there Dutch mini-cigars, which he passionately smokes 10 to 12 of a day and which have become a special trademark of his personal style. Auster’s enthusiasm for the particular Schimmelpenninck brand’s “Media” cigarillos (dry-cured and machine-made in Holland, and sold in 20s in metal tins) is so remarkably strong that it is passed over to his fictional characters Peter Aaron (Leviathan), Paul Benjamin (Smoke) and James Freeman (from the recent novel Invisible). “What are you smoking these days?” someone asks Leviathan’s protagonist Peter at one point, and he replies: “Schimmelpennincks. The same thing I’ve always smoked.”22

It does not even matter whether at this point one is thinking of the empirical Paul Auster, or the figure of the writer “Paul Auster” that one has constructed through a collage of bits and fragments gathered from his interviews and book reviews, or the implied author of his books, or even his...