![]()

PART ONE

Prehistories

CHAPTER ONE

From ‘Mach Schau’ to Mock Show: The Beatles, Shea Stadium and Rock Spectacle

Jeffrey Roessner

As The Beatles nervously helicoptered over Shea stadium before their concert on 15 August 1965, the opening date of their second US tour, they were stunned by the enormous crowd awaiting them and equally dazzled by the thousands of flashing camera bulbs. They were originally scheduled to arrive dramatically at the show itself by copter – something they had done for at least one previous outdoor performance – but safety concerns meant that they instead landed at the nearby World’s Fair building and then were shuttled via Wells Fargo armoured car to the stadium. The literal approach to the show fairly well captures the extreme contrasts of their lives at this point. Touring was not tourism, as the band suffered a fairly merciless captivity on the road, trapped in the claustrophobic spaces of hotel rooms, cars and airplanes, and everywhere besieged by hysterical, clawing fans. But those suffocating spaces only represent half of the extremes they endured. Starting with large venues on the 1964 world tour, they would be propelled suddenly from their cramped quarters into the middle of a howling vortex, a vast expanse of space and volume that was the rock stadium show.

As in so many areas of rock music, The Beatles pioneered the massive stadium show, establishing a pattern hewed to by virtually every major band that came after. At this point in popular music history, the details all had to be sorted out, from handling the volume of ticket sales to establishing a sound system (inadequate though it was for the Shea concert) and attending to serious crowd control. In terms of numbers, Shea was a pop music concert of firsts and bests: largest audience (55,600), largest overall take ($304,000), largest fee for a band ($160,000) (Lewisohn 1992, 199). The concert was even filmed – a prescient move that resulted in the first concert film by a rock band. But amid all of these record-setting details and the sense of culmination the concert represents, it also has a sense of finality. Despite the exuberance generated by the mass of screaming fans, this stadium show embodied the contradictions exposed by The Beatles’ success. Even as they heralded a new age of monumental live rock performance, they were nearly finished with it.

In retrospect, The Beatles’ touring career seems remarkably compressed, and thus stunningly intense. Their first proper international tour began with dates in Sweden in October 1963, and they arrived in America to begin the famed invasion on 9 February 1964 – a visit that included their legendary first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show and concerts at Washington Coliseum and Carnegie Hall. Their final performance occurred at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on 29 August 1966, marking the end of a career as international performing artists that lasted just under three years. No other band before or since has created such a formidable legacy in such a short span on the touring stage. In this chronology, the first Shea stadium show stands at the exact mid-point of their three official US tours, which began in August of 1964 and ended in August of 1966. This timeline appears too neatly balanced, however, and it obscures the show’s significance. The concert didn’t so much mark a new, sustainable level of success for the group as it was a dazzling climax followed by a fairly abrupt denouement.

The audacious plan to stage the Shea concert was conceived by New York impresario Sid Bernstein. Months before The Beatles’ first visit to the United States, Bernstein had angled to book the band into Carnegie Hall, a bravura move that paid off handsomely as their success crested with the ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ single. In 1965, Bernstein had an even bigger coup in mind: a stadium show several times larger in magnitude than any that had been seen before by fans of pop music. It would be a triumphant moment for The Beatles and for New York – if he could sell the tickets. The idea for the show must have struck Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein as at least a bit of a gamble, given that Bernstein sealed the deal by agreeing to buy any unsold tickets (see Schwensen 2014, 41). Fiercely protective of ‘the boys’ and ever-mindful of their image, Epstein had been reluctant to have The Beatles play in less than sold-out venues. By the 1965 tour, their momentum had mitigated the risks, though Epstein would not book them consistently into such enormous spaces for another year.

At the show itself, despite the enormous efforts to plan and stage an event of such magnitude, The Beatles apparently never considered deviating from the norm for their performances at the time. After multiple warm-up acts, they played a short set comprised of just twelve numbers.

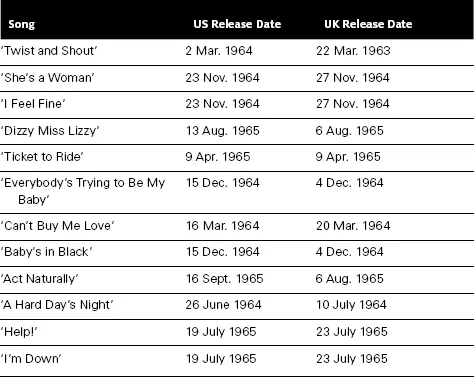

TABLE 1.1 Songs performed at Shea

The song choice here represents chestnuts of their repertoire (‘Twist and Shout’ and ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzy’), recent singles (‘Ticket to Ride’ and ‘Help!’) and, as always, vocal spotlights for George (‘Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby’) and Ringo (‘Act Naturally’). The entire affair lasted all of thirty-seven minutes – which seems ridiculously short by contemporary standards, but which was routine for them (Schwensen 2014, 181).

Despite its brevity, the set-list was neither dated nor musically constraining. Nine of the songs had been released within the previous year, with five of them alone from 1965. The only surprises here for the fans would have been ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzy’, which had just come out on the US Help! album, and ‘Act Naturally’, which had not been released in the United States until a month later.1 So as of the late summer of ’65, although they had shown remarkable ingenuity as songwriters and were beginning to emerge as studio craftsmen, The Beatles hadn’t yet fully exceeded their capacity to play their material live. The first stop upon arrival in the United States was the Ed Sullivan show, where they taped performances of six songs, all part of the Shea set-list, with one notable exception: McCartney did a solo presentation of ‘Yesterday’, backed with pre-recorded strings. The song was a considerable step forward musically, with its string quartet setting and its sophisticated harmonic approach, and they wouldn’t include it in their concert set-list until the following year. Otherwise, on tour in ’65, The Beatles essentially still played what they recorded.

In terms of The Beatles’ lives as performers, then, the first Shea concert was perfectly timed – the audience still thrilled by the striking originality of the band, the songs still fresh and The Beatles themselves not yet so completely jaded, disillusioned with the sound and their performance, that they couldn’t be awed by the experience. Reflecting on the show some thirty years later for The Beatles Anthology, assistant Neil Aspinall notes, the amazement still apparent in his voice, ‘That was a good experience. That was the first really big open air – “Wow, look at this”.’ Even the normally cynical Lennon would later remark, ‘at Shea stadium, I saw the top of the mountain’ (quoted in Anon 2008). The film of the concert wonderfully captures the awe-inspiring sight of the mostly young, mostly female crowd: the camera pans across the pre-concert bowl of empty seats, then in a series of cuts shows them steadily filling with fans who wind up to fever pitch, loosing an unflagging torrent of screams.

Given the responses to the show from The Beatles and the fans, it’s not surprising that the concert has attained mythical status, and for many good reasons. Not that many people in America had been able to see them because they undertook only three full-length tours of the country. Moreover, the crowd of 55,600 at Shea set a record that, remarkably, stood for almost eight years, until Led Zeppelin broke it in Tampa, Florida, on 5 May 1973 (see Lewis 2006, 208). But particularly in the contemporary Internet age, aggrandizement and simple misinformation about the concert abound. A host of websites, for example, repeat the claim that Shea was the first rock concert held in a US sports stadium.2 In fact, it wasn’t The Beatles’ first show in an American sports stadium, let alone the first rock concert held in one. Both as part of a bill and as headliner, Elvis Presley had routinely played outdoor venues, including stadiums, in the 1950s. He had played open-air baseball fields as early as 1955, and he later performed at, among others, the Cotton Bowl (11 October 1956); Memorial Stadium in Spokane, Washington (30 August 1957); Empire Stadium in Vancouver, Canada (31 August 1957); Sick’s Stadium in Seattle, Washington (1 September 1957); Multnomah Stadium in Portland, Oregon (2 September 1957); and Honolulu Stadium in Hawaii (10 December 1957) (Guralnick and Jorgensen 1999, 86, 109, 110). The Cotton Bowl is generally credited as being the largest of these shows, with an attendance of 26,500 – marking a record that stood until 1965, when The Beatles played Shea for the first time (Schwensen 2014, 41).3 As for open-air sports stadium shows by The Beatles, they played four on the 1964 North American tour.4

Nonetheless, the mythology continues to outstrip the facts – in part no doubt because of the slippery definition of a ‘large’ stadium. For example, despite listing these shows at the end of his book Ticket to Ride, Larry Kane – a reporter who travelled with the band on their 1964 and 1965 US tours – suggests that Brian Epstein had ‘determined in 1964 that The Beatles would not play large outdoor stadiums’ for fear that they wouldn’t sell them out (Kane 2003, 178). But some of these earlier stadium shows were quite big: at capacity, the Gator Bowl could seat 32,000 fans, while the Municipal Stadium in Kansas City would hold 40,957.5

TABLE 1.2 Open-air sports stadium dates on the 1964 tour

Still, The Beatles’ first Shea concert certainly outdid all their other shows in terms of attendance. On their previous North American tour, three stops had breached the 20,000 mark (Empire Stadium, the Gator Bowl and Municipal Stadium in Kansas City), but more typically, on tour in North America The Beatles played before crowds that averaged roughly between 12,000 and 18,000 fans – not so different from the numbers than Elvis racked up in the 1950s (see Guralnick and Jorgensen, 1999). So at Shea The Beatles played to an audience over three times larger than usual.

If Shea was the apex, the fulfilment of all the grand ambitions of Epstein and The Beatles, it was also, however, the start of their demise as a touring band. From his very early days managing the band, Epstein confidently averred that the band would be bigger than Elvis (Lewisohn 2014, 499). All along, The Beatles were also keenly aware of the lack of success of British artists in America: the biggest home-grown heroes, such as Cliff Richard and The Shadows, hadn’t made a dent in the pop music charts across the Atlantic. After the triumph of the Shea concert, though, The Beatles had unequivocal proof that, numerically at least, they were bigger than the King of rock ’n’ roll, and they had indeed conquered America. The contradictions embedded in that very success, however, pulled them apart as a touring unit.

One way to understand the splintering of The Beatles as a live ensemble involves the story of distance. In Liverpool and particularly at the Cavern, The Beatles recognized few boundaries between themselves and the audience. They openly ate, drank and smoked on stage, and the female Cavern dwellers in particular regarded them as their own: the fans passed song requests to the band on stage, visited them in the tiny space that passed for a dressing room and, for that matter, could easily ride the bus with them to their early gigs. The band drew much-needed energy from these crowds, even the unruly, sometimes violent clientele of the Reeperbahn clubs in Hamburg. But as much as they cultivated such intimacy, The Beatles also developed a sense of style, of showmanship, that distanced them from the audience. In Hamburg, they were famously instructed to ‘Mach Shau’, or make a show, in order to incite the audience and pull customers into the club to buy alcohol (quoted in Lewisohn 2014, 359). Fulfilling the duty of bar bands everywhere, they invented an energetic, at times provocative stage act that succeeded wildly, with band members stomping on the stage, yelling at the crowd, even jumping into the dancing beer-hall fray (see Stark 2005, 94). Lennon in particular became known for his outrageous antics, which included shouting ‘Heil Hitler’ to the German audiences, doing his spastic and ‘cripple’ routines and mocking other members during performance. But the frontline of the band as a whole – John, Paul and George – all developed a comic sensibility and repartee that captivated the fans.

The Beatles’ attractiveness rested on a tension between these two conflicting drives: intimacy and distance. The fevered pitch of Beatlemania in fact grew out of a particular kind of distance: the exotic. When The Beatles arrived in Hamburg on their first trip, they fascinated the Germans because of their foreignness. Not only did they import rock ’n’ roll music, but their stage manner and look immediately transfixed the audience. Describing her first reaction to the band, Astrid Kirchherr confirms the appeal: ‘I was shivering all over the place . . . There was so much joy in their faces, the energy in their eyes’ (quoted in Stark 2005, 95). The Beatles themselves had the opposite response: for their part, they were struck by the appearance and attitude of the Germans. The band absorbed the dark, European look of their new friends, culminating, of course, in their adopting the famous hairstyle, with bangs brushed forward. The relationships here had a peculiar symmetry. For the Germans, the British band – in all its naïve parochialism – represented an unfamiliar otherness, just as for The Beatles, the Germans held an exotic charm, which they mimicked in their own way. Indeed, when The Beatles returned to Liverpool from their first trip to Hamburg, some fans thought they were going to see a German group because they were billed as ‘Direct from Hamburg’ (Bramwell 2005, 2). That distinction of foreignness and the distance from the everyday heightened their appeal and created an aura that would be vigorously promoted in America.

As the band grew ever-more staggeringly successful and lost its basis in local culture, more boundaries were erected – at first in the name of professionalism, but ultimately for the sake of safety, both for themselves and for the audiences. As Epstein began his tenure as manager, officially in January 1962, he instituted a number of changes in the band’s appearance and the venues they played, all to bolster their appeal as proper entertainment. He banned smoking, drinking and eating on stage as a first measure. But he also radically transformed their stage act itself: ‘Out too went th...