- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

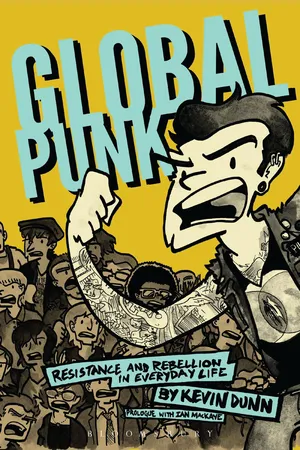

Global Punk examines the global phenomenon of DIY (do-it-yourself) punk, arguing that it provides a powerful tool for political resistance and personal self-empowerment. Drawing examples from across the evolution of punk – from the streets of 1976 London to the alleys of contemporary Jakarta – Global Punk is both historically rich and global in scope. Looking beyond the music to explore DIY punk as a lived experience, Global Punk examines the ways in which punk contributes to the process of disalienation and political engagement. The book critically examines the impact that DIY punk has had on both individuals and communities, and offers chapter-length investigations of two important aspects of DIY punk culture: independent record labels and self-published zines. Grounded in scholarly theories, but written in a highly accessible style, Global Punk shows why DIY punk remains a vital cultural form for hundreds of thousands of people across the globe today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Punk by Kevin Dunn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Punk Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Punk Matters:

DIY Punk and the Politics of Resistance

This is a book about punk rock, why it matters to so many people around the world, and why it should matter to you. While the scope of the book is broad—examining punks and punk scenes from across the globe and over the past four decades—the argument is quite straightforward: DIY punk provides individuals and local communities with resources for self-empowerment and political resistance. Over the last several decades, despite repeated claims that “punk is dead,” punk has become a global force that constructs oppositional identities, empowers local communities, and challenges corporate-led processes of globalization. Punk has changed the world and continues to do so, at the individual, local, and global levels.

What is punk?

For anyone involved and interested in punk, just defining “punk” is to enter into a hotly contested debate. Where does one draw the lines? Is Green Day punk? What about Rancid or Blink-182? Get a dozen punks together in a room, ask them to define punk and you’ll get eighteen different answers. One of my favorite observations about defining punk was made by Michael Muhammed Knight in his novel Taqwacores, a fictional account of Muslim American punks that helped spawn the real-life Taqwacore scene. Early in the novel, Knight’s narrator muses: “Inevitably I reached the understanding that this word ‘punk’ does not mean anything tangible like ‘tree’ or ‘car.’ Rather, punk is like a flag; an open symbol, it only means what people believe it means” (Knight 2004: 7; italics in original).1 Punk, like a flag or any other open symbol, is something many people feel passionate about, but have a hard time agreeing on its shared meaning.

The laziest scholarship on punk treats it as a unified, cohesive community. But those on the inside know how false such a claim can be. More nuanced scholars writing on punk begin with the observation that it is impossible to define punk, but then they inevitably start talking about punk as if they have a clear understanding of what it is. Even though scholars might agree that it is an open-ended concept, they attach their own meanings to it. I am no different. But I will try to make my distinctions and definitions clear throughout this book.

When most people think about punk, they immediately think about music, and maybe clothes and hairstyles. After all, it was the music and the fashion that grabbed people’s attention back in 1976 and 1977, when punk first emerged as a cultural thing. While the average citizen of London might not have heard a punk song, it was hard to miss punks in public, as they tended to generate a great deal of attention while riding the Tube or walking down the street. While there was no common “uniform,” their shared rejection of accepted fashion norms meant that punks stood out in ways that might be hard to imagine today. At a time when clothes were mundane, punks were wearing layers of dayglo fabrics, jackets with slogans spray painted on the back, clothes ripped and safety-pinned back together, t-shirts with provocative images, patches with swastikas and/or the Union Jack, or any variety of styles mashed together. Hairstyles included Mohawks, shaved heads, dreadlocks, spikes, and dyed or disheveled hair. The overall result was a rejection of the status quo, and that often generated a violent response, such as when Ari Up, the lead singer of the all-female band the Slits, was stabbed in the buttocks by an angry passer-by. As the Slits’ bassist Tessa Pollitt recalls, “When we started dressing the way we did—just trying to be the rebelliousness generation, not even consciously—it was quite violent. Especially, even more so as women, because we were just like aliens to the rest of society” (interview with Tessa May 28, 2015). Likewise, the music was a dissonant assault on the established norms of rock’n’roll. In New York City, the Ramones’ two-minute pop songs were delivered at blistering speeds and volumes, while in London the Sex Pistols’ live shows were a display of intensity and aural chaos.

The cultural grounding was almost always the music, but how can one characterize punk music? What similarities did early London punk bands like the Sex Pistols, Damned, Slits, Clash, X-Ray Spex, or Raincoats have in common? Aurally speaking, these bands were each quite distinct. For instance, the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK” sounds like a traditional rock’n’roll song, while the Clash’s “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais” has a strong ska vibe, and the Slits’ “Instant Hit” has more in common with reggae and jazz than rock. And as punk evolved, the music became even more diverse as punks took a Western rock core and (re)infused it with reggae, folk, blues, Brazilian salsa, techno, industrial, and just about every other musical style and genre you can think of. To define punk in musical terms is an impossible feat. Which isn’t to say that people don’t try. Or, more significantly, that major corporations haven’t constructed a “punk sound” that they can market. The mainstream media may sell the idea that playing brashy, loud three-chord pop songs with vocals sung in a fake British accent is “punk” and that leather jackets, pants with 950 zippers and safety pins, and a black t-shirt with a pink skull and crossbones on it is “punk.” But those are cartoon caricatures invented to sell a manufactured product.

Unsurprisingly, the corporate music industry responded to the organic emergence of punk by trying to appropriate it and turn it into a musical “niche,” or more often, a marketing strategy. Bands sound “punk” if their songs are short, high-energy, and have few chord changes. So musical acts like Avril Lavigne and Blink-182 get marketed as “punk.” Bands can release their “punk” album if it fits into this category—supposedly U2’s “Achtung Baby” and Kanye West’s “Yeezus” are punk albums if their publicists are to be believed. But those publicists shouldn’t be. Early punk bands in the London and New York scenes were extremely diverse musically. There was no single “punk” sound then. Nor is there one today. Current bands like the Evens, Dott, or the God Damn Doo Wop Band don’t fit the corporate music industry’s definition of “punk music” because that definition is meaningless.

I understand punk to be a social practice, or sets of social practices. What made those bands that I listed earlier—the Sex Pistols, Damned, Slits, Clash, X-Ray Spex, and Raincoats—punk was not so much how they sounded, but how they acted. Punks worked to imagine new ways of being. As they loudly proclaimed at the time, they were sick and tired of the crap that mainstream culture was shoving down their throats, whether it was music, art, literature, or fashion, and they decided to make their own cultural products. Punks did so by making their own music, being their own journalists and writers, making their own movies, designing their own clothes. It was a two-part process: a rejection of the status quo and an embrace of a do-it-yourself ethos.

So when I talk about punk as a set of social activities, as opposed to a specific, fixed musical style or fashion of clothes, I am particularly focused on this notion of do-it-yourself. This book is on DIY punk, a term used by many to draw attention to the difference between the organic cultural products that emerge from a DIY punk community and those “commercial punk” products sold by major record labels and trendy mall stores such as Hot Topic. Of course, sometimes things cross that border. After all, a band like Green Day emerged from one of the quintessential DIY communities, the Gilman Street punk scene of the Bay Area in the early 1990s (Boulware and Tudor 2009). But as I will discuss later in the book, they crossed over from DIY punk to commercial punk. Thus, there is a huge difference between Green Day and, say, Crass or Fugazi, and those differences have more to do with social practices than with musical styles. DIY punk is politically significant in ways that commercial punk is not. In fact, the commodification and appropriation of punk has frequently undermined the effectiveness of DIY punk’s political and social relevance. That struggle is one of the primary themes underpinning this entire book. Ultimately, being a DIY punk has little to do with what you are wearing or listening to and everything with how you choose to interact with the world around you.

The DIY aspect of punk was one of its core elements at the outset of its creation. Partly as a response to the bloated, alien popular cultural forms prevalent in the 1970s, punk emerged in the US and UK around an ethos of do-it-yourself. Before punk’s emergence, the dangerous aspects of rock’n’roll had been effectively appropriated and sanitized by the corporate music industry. Bands like Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and the Who had become “major rock acts,” signifying their transformation into corporate business entities, playing in huge arenas with expensive ticket prices. Music and musicians were increasingly disconnected from their audience. Rock musicians were elite millionaires living extravagant lifestyles with little in common, and little to say that was relevant, to fans who were now regarded primarily as consumers. This relationship was not just in music, but repeated across the spectrum of popular culture in film, television, books, and so forth. By the 1970s, corporate capitalism had reframed culture as products to be packaged, marketed, and sold to passive consumers.

In large part, the emergence and success of punk was a response to this capitalist relationship to culture. At its core, punk was a dual rejection. On one level, punks were rejecting the banal cultural products that were being sold to them, from music to fashion. This is pretty well-worn territory, and most books and documentaries about the emergence of punk will juxtapose the stagnant behemoth “rock stars” of the early 1970s promoted by the corporate music industry (Genesis, Yes, Pink Floyd, and so forth) with the three-chord misfits that became the punk vanguard, whether they be the Dictators, the Dickies, the Ramones, or the Undertones. Many of these bands explicitly stated their opposition to such bloated cultural icons, as the Clash proclaimed in their song “1977” that “Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones” would no longer be relevant that year. Other punk cultural producers similarly rejected the dominant corporate culture, because it said little about their lives. One can see this in the writings produced by punk zinesters (discussed in Chapter Six), in punk-influenced films and art (see Thompson 2004; Turcotte and Miller 1999; Bestley and Ogg 2012), and in fashion produced by the likes of Vivienne Westwood, who stated “I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way” (Westwood 2002). Again, most histories of punk will note that punk was born as a reactionary or revolutionary response to the stagnancy of Anglo-American 1970s culture, so I don’t want to belabor the point too much, though it is a highly important one because one must understand that punk, from its outset, was rebellious and fundamentally anti-status quo.

On a more important level, punk involves a rejection of the passive role of consumer. By tearing down the artificial boundaries between performer and audience, punk proclaims that anyone can be a cultural producer. But more significantly, it states that everyone should be a cultural producer. The cultural forms generated by corporate capitalism are built upon the illusion of the professional: “Don’t try this at home, these are experts in their field, whether that field be making music, writing a book, making a movie, acting in a play, or what have you.” As explicitly as it can be, punk is a loud rejection of that mentality, proclaiming: “Fuck that, you should try this at home.” You might not be able to write or play as technically proficient as F. Scott Fitzgerald or Eric Clapton, but that doesn’t mean your voice and views aren’t as equally important. By championing the DIY ethos, punk is the intentional transformation of individuals from consumers of the mass media to agents of cultural production. It is a rejection of passivity and a championing of personal empowerment.

Of course, punk was not the first cultural form to champion a DIY ethic. An active zine culture had been promoting self-publishing for several decades. Earlier in the twentieth century, the musical form of skiffle had become popular, championed by such artists as Lonnie Donegan. Blending folk music with jazz and blues influences, skiffle was regarded as a democratic form of music, employing home-made or improvised instruments. Washboards played with a thimble became a popular form of percussion, accompanied by a kazoo, jug,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue. Punk Won: A Conversation with Ian MacKaye

- 1 Punk Matters: DIY Punk and the Politics of Resistance

- 2 You’re Not Punk and I’m Telling Everyone: Oppositional Identities and Disalienation

- 3 Fuck Your Scene, Kid: The Power of Local Scenes

- 4 Punk Goes the World: Global Networks, Counter-Hegemony, and the Contradictions of Globalization

- 5 If It Ain’t Cheap, It Ain’t Punk: Punk Record Labels and DIY as a (Anti-)Business Model

- 6 Satan Wears a Bra While Sniffin’ Glue and Eating Razorcake: Punk Zines and the Politics of DIY Self-publishing

- 7 Total Resistance to the Fucking System: Anarcho-punk and Resistance in Everyday Life

- Postscript. Punk Rock Won’t Change the World, It Already Has

- Notes

- References

- Index

- Copyright