![]()

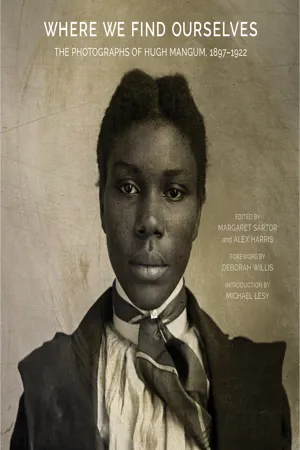

WHERE WE FIND OURSELVES

MARGARET SARTOR

TO TELL THE STORY of photographer Hugh Leonard Mangum’s brief life I have had to rely on a handful of recorded facts, his own scribbled notes, passed-down recollections, numerous publications from his era, and an old traveling trunk. Interesting stuff, but not much from which to construct a biography. In comparison to that relatively small accumulation of what we know about the photographer, the speculation and stories generated by the portraits he left behind are very nearly inexhaustible. And the lives behind these portraits, like the scattered facts we know about Hugh Mangum, are, in many ways, the more compelling for their incompleteness. The gaps in our understanding lead us to consider more carefully what we know or, more importantly, what we think we know. The people in these portraits stare back at us across a hundred years of time’s passing, through the indelible marks of damage and disregard. We may think the difference of a century considerable, and in so many ways that is true. But these portraits suggest that the distance between then and now, them and us, is a lot closer than we might expect.

It would be impossible to identify and uncover the life stories of everyone who visited Mangum’s studio, but by immersing myself in the historical record, I hoped to better understand the texture of those lives and to get as close as possible to seeing as Hugh Mangum saw—or at least to cultivate a more nuanced appreciation of his way of seeing. This proved to be an endlessly compelling education, both factually and visually. And it became more than that. Over time, I began to feel that I, like Mangum, was itinerant. Moving from archive to archive, and face to face, it was as though I were traveling to places familiar yet unfathomable, to a time that was distant but also in need of my immediate, if not urgent, attention.

—

A DARK-HAIRED BOY WITH HAZEL EYES, Hugh Mangum was born in 1877, the last year of Reconstruction, in the tobacco-fueled boomtown of Durham, North Carolina. The eldest of five children in a hard-working, well-respected family with a web of kinship that spread out across the county, Hugh was cut from a somewhat different cloth. Unlike his brother, Leo, and sisters, Patti, Lula, and Sallie, who, like their parents, aspired to a farming life, Mangum thought of himself as an artist from a young age.

It would have been easy for Hugh Mangum to pursue farming, factory, or mill work. His father, uncles, and cousins had their hands in a number of local business endeavors. But there were few options in Durham for a boy who was inclined toward drawing and painting. He had to find opportunities to learn where he could. As a boy of twelve, he took art classes at a local women’s college. Mangum is mentioned in an 1889 edition of the Durham Sun as a pupil in the Methodist Female Seminary’s art department, the only male in a long list of teachers and students whose work was being displayed in a “meritorious exhibit” in a downtown art gallery. He and his siblings were all musical; beyond his engagement in the visual arts, Mangum played the mandolin, accordion, and piano.

In recollections made years later, Leo Mangum claimed that his brother was invited at the age of sixteen to attend Trinity College (later Duke University) but instead chose to study fine arts in Winston-Salem at Salem College. Salem was, and is, the oldest educational institution for girls and women in the United States and was established by the Moravian Church in the belief that girls and women were entitled to the same education as boys and men. Since its founding, it has accepted students from diverse backgrounds, including African Americans and Native Americans, as members of the school community. It has also continually accommodated people who desire “special arrangements” in order to take advantage of their courses and facilities. In order to pursue an education in the fine arts, Mangum had to push across the boundaries of what was generally considered appropriate for a man’s education, experiences that would have affected his ideas about society. Studying alongside women, who were beginning to claim new freedoms of their own, may have fostered some rebellion against mainstream expectations. At the very least, it helps to explain his remarkable ability to put female sitters at ease in front of his camera.

Another indication of Mangum’s unconventionality is that on his own, as an adult, he studied hypnotism; he even received certificates in the practice. In the nineteenth century, hypnotism (or mesmerism, as it was sometimes called) was considered more than a parlor trick, and its practice greatly influenced the burgeoning but controversial field of psychology. As for Mangum’s intentions, we can only speculate. But the curiosity that motivated his interest dovetails, in engaging and evocative ways, with his ambition as a portrait photographer.

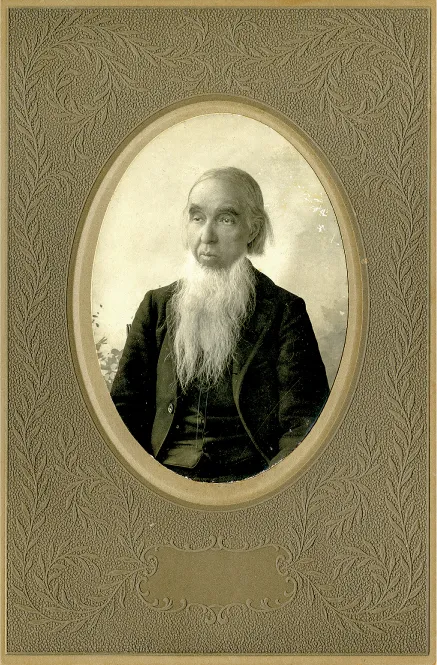

Presley Jackson Mangum, original print by Hugh Mangum, ca. 1897–1905. Courtesy of the Mangum and Latta Family Collection, Durham County Library, Durham, North Carolina.

Hugh Mangum’s father, Presley Jackson Mangum, was a skilled carpenter and farmer, briefly operated a restaurant, and for a time served as Durham’s postmaster. Mangum’s mother, Sally Farthing Mangum, was sixteen years younger than her husband, raised poultry, and was known for her impressive vegetable garden. While Mangum and his younger siblings were growing up in their home on Main Street, their father operated a small factory near downtown on Pettigrew Street that made sashes, blinds, and the occasional coffin. Pettigrew Street ran parallel to Main, separated by a city block and the railroad tracks that bisected the town. As Durham’s population grew in the late nineteenth century, the land spreading north from Main Street, away from the railroad tracks, became a predominantly white residential area. The land on the other side of the tracks, spreading south from Pettigrew, became home to a largely self-sufficient African American neighborhood known as the Hayti District. Pettigrew was not only Hayti’s busiest business street but also served as the unofficial boundary separating black and white people as they went about their daily activities. For the young Hugh Mangum, a walk from his family home to his father’s factory would have taken him directly into Hayti.

Presley Mangum was in his mid-forties when Hugh was born, and when his youngest child, Sallie, came along in 1890, he was nearing sixty. Not long after Sallie’s birth, Presley looked for a summer refuge for his family, away from the bustling downtown, and purchased a farm in a nearby community known as West Point on the Eno. The property had a substantial house surrounded by well-kept fields, gardens, barns, and a stand of fruit trees. Next door there was a mill that had been in continuous use since the 1780s. At the farm, in the second story of a packhouse barn once used to store tobacco as it cured, Mangum built his first darkroom, using tar to seal the gaps between boards and drawing water from a nearby tributary of the Eno River. On a pine board, just inside the narrow doorway, he wrote, in a heavily and elaborately penciled script suggestive of a proud teenager staking his territory: “Hugh Mangum’s Dark Room.” Other penciled, dated notations by Mangum on the pine walls indicate that he continued to use this darkroom for many years. In another part of the packhouse, reachable only by ladder, he found a place to store his glass plate negatives. By 1893, the Mangum family had left their downtown home and moved to the farm permanently. Leo Mangum, who outlived his older brother by more than four decades, lived on the farm at West Point on the Eno until his death in 1968.

Before 1860, Durham was little more than a cluster of wood frame buildings surrounding a small depot. But its rapid growth after the Civil War prompted people from many occupations, including photography, to set up business and offer their trades and services. In that era, the practice of photography was commonly learned by apprenticing to an already established professional. Securing such a position would have been an easy undertaking for the outgoing and artistic Hugh, who grew up only blocks from several successful studios.

The first recorded photographer to set up shop in Durham, Edward Featherstone Small, opened a studio the year before Mangum was born, in 1876. Small practiced his profession until 1882, when W. Duke, Sons & Company hired him as a traveling salesman. (It was Edward F. Small who invited a popular French actress to pose for a life-size lithograph that showed her holding a package of Duke cigarettes, initiating an advertising strategy that proved wildly successful for the emerging tobacco giant.) Of the longer-lasting photography studios in Durham in the nineteenth century, Charles Rochelle’s business lasted from the 1880s until the late 1890s; William Shelburn, the most popular photographer in Durham from the 1880s until 1906, was Rochelle’s biggest rival. Durham’s first woman photographer, Katie Johnson, was in business by 1900, specializing in children’s photographs, and the first African American photographer, David F. West, opened shop several blocks southeast of downtown in 1902. The J. W. Thomas Gallery produced photographic portraits in a studio on Main Street under the imprint Thomas & Hobgood from approximately 1896 until 1898, when the gallery was purchased by Oliver Cole and Waller Holladay, business partners who operated studios in both North Carolina and Virginia.

Patti, Lula, and Sallie Mangum, original print by Hugh Mangum, ca. 1895–97. Courtesy of the Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The most likely candidate for an association with Hugh Mangum is the J. W. Thomas Gallery, which was in operation during the years that Mangum first began to make photographic portraits. Antique prints embossed with the Thomas & Hobgood emblem include a unique hand-painted backdrop that also appears in many of Hugh Mangum’s glass plate negatives, some dating to 1897. It seems plausible that Hugh Mangum may have worked in the J. W. Thomas Gallery after studying at Salem College and before striking out on his own as a photographer in 1899. It’s also possible that he purchased equipment and materials from the defunct Thomas & Hobgood business to help launch his career.

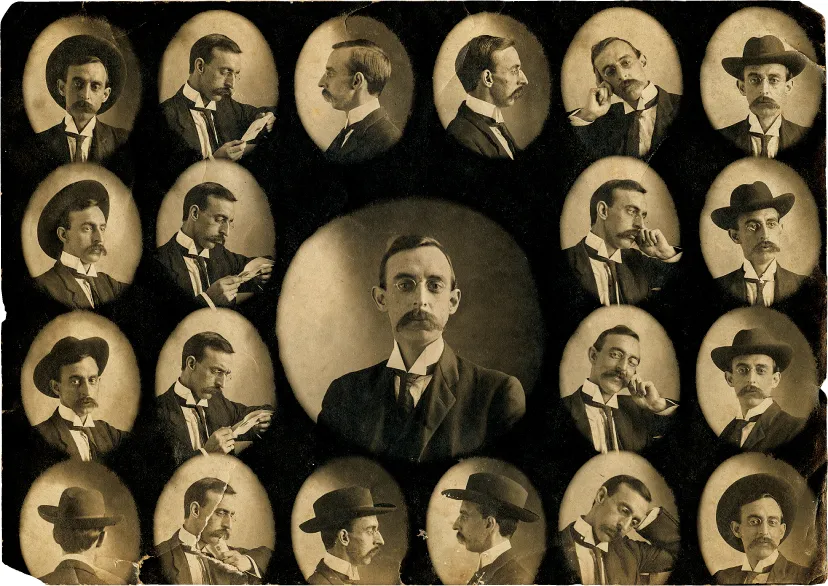

Self-portrait, original print by Hugh Mangum, ca. 1905–10. Courtesy of the Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

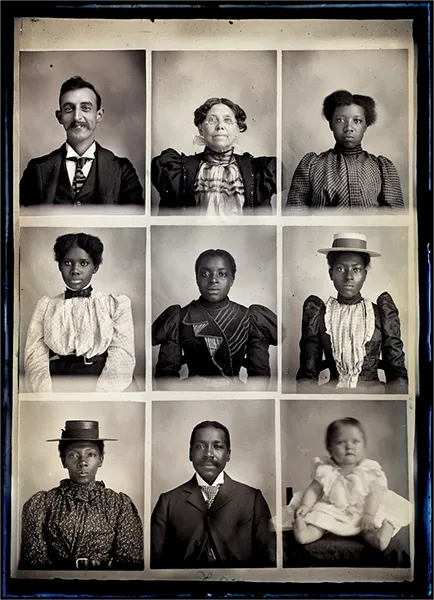

By the time Hugh Mangum turned eighteen in 1895, he was taking photographs of family members and printing them in his packhouse darkroom. His earliest dated professional portraits—of non–family members in a studio setting—were recovered as glass plate negatives from a box marked, in Mangum’s own handwriting, September 19, 1897, the year he turned twenty. These early multiple-image glass plate negatives, which may have been made while in the employ of J. W. Thomas or another studio photographer, include pictures of identifiable residents from both the white and black communities of Durham.

In early 1899, according to the Durham Sun, Hugh Mangum purchased the Cottage Gallery in Durham. And he was listed, for the first and only time, in the Durham City Directory, 1899–1900, as a photographer with a business at 209 West Main Street—possibly the large, sky-lit space that was occupied a few years later by the Cole & Holladay Studio. By June 1899, the Durham newspaper was wishing the local boy well on his move to Winston.

Fortunately for us, at the outset of his career Hugh Mangum began keeping a handwritten log of his movements. At first the travel log is irregular and incomplete, written on what appears to be the decorated cardboard divider of a suitcase. It corroborates that Mangum traveled to Winston-Salem in mid-June 1899 and left there on August 1. According to the log, he then settled in Greensboro for four months; in December, he returned to Durham. During 1900 he listed eight different towns in North Carolina and Virginia in the order in which he visited them, with three separate trips to Charlottesville, but did not include the specific dates of his travel. In the U.S. Census of 1900, Hugh Mangum lists his residence as Durham and his profession, tellingly, not as photographer but as “artist.”

By 1901, Mangum’s travel log had a format. He had begun to include not only the names of the towns he visited, but also the dates he arrived and left. In the margins he occasionally added a cryptic personal note about a specific day, such as “Old Cherry Tree 5/17/06.” In May 1903, when Mangum acquired a large roller-tray trunk—“the most convenient trunk ever devised”—he duly noted his purchase on the inside of the trunk itself. And on the outside, in large bold letters, he painted “H L Mangum Photographer.” Thereafter Mangum continued his relatively thorough, if haphazardly written, list of towns and dates on the large trunk’s inside lid. He seems to have kept the log entirely for himself. The writing is untidy and occasionally illegible; he often wrote in a private shorthand. Still, the combined logs, spanning the years from 1899 to 1919, provide some of the best clues we have about how Hugh Mangum worked.

For example, from the log we know that Mangum consistently returned to Durham every few months, and that for many years he returned and remained at the Mangum family farm from mid-December through the new year. When in Durham, Mangum set up his Cottage Studio in a tent or temporary space near downtown and announced his location, along with his opening and closing dates, on printed broadsides. Some of these broadsides survived, stacked among his glass plate negatives. They promote “All Kinds of Pictures” and “Specials to School Children.” “Come at once,” he urged in underlined letters, “and avoid the rush.”

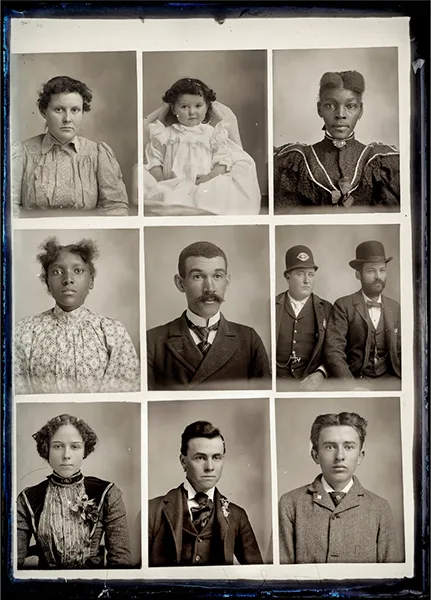

Hugh Mangum (top row, left), ca. 1897–1902.

Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore (center row, center), Durham’s first African American physician, and Senator Marion Butler (center row, far right), a Populist leader and advocate of “fusion politics.” Durham, North Carolina, ca. 1897–1902.

Newspaper accounts indicate that in the early 1900s Mangum sometimes managed a “gallery over Daye’s Shoe Store” in Winston-Salem, but also that he had begun his itinerant work. In 1902, newspapers mention that he had partnered with a photographer named Cobb to open affiliated studios in Greensboro, Marion, and Raleigh, North Carolina. Around that time, Mangum created an advertisement for “The Mangum & Cobb Photo Company, of New York, with Southern Headquarters now at Raleigh” that included the declaration, “We LEAD—Others TRY to Follow.” Mangum’s travel log doesn’t show that he went to New York, and it also doesn’t show that he visited Washington, D.C.—yet he left behind mounted photographic prints of the Capitol and the newly completed Library of Congress building that appear to be his photographs. There are other vintage prints and advertisements from the 1900s showing that he made photographs for the Dixie Photo Co. and in partnership with other photographers under the imprint of the Novelty Photo Co. We know from vintage prints mounted inside cardboard frames engraved with his studio’s name that from 1906 to 1919 he operated the Mangum Studio, seasonally, in East Radford and Pulaski, Virginia. And for two years prior to his death in 1922, he operated the Mangum Studio in Roanoke, Virginia.

Hugh Mangum’s nephew, Jack Vaughan, was born in 1911. He knew his uncle well. Decades later, in the 1970s, Vaughan played a crucial role in helping to salvage and save Mangum’s glass plate negatives. In an interview from the early 1980s, Vaughan recalled that his uncle liked to “roam” and, as a rule, would “ride the rails until his money give out then come back [home].” At its peak in the early 1900s, the Durham depot served twenty-nine passenger trains a day; with five different railroad lines spreading out like the arms of a starfish, the possibilities for Hugh Mangum to roam were nearly boundless.

Hugh Mangum’s open-door policy of welcoming a racially diverse clientele may have been unconventional, disdained by some and embraced by others, but in some counties, in some years, it may also have been illegal. In 1896, in Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the concept of “separate but equal” was constitutional; its ruling supported the racial segregation of public facilities, such as passenger trains and depot waiting rooms. Though different cities and counties segregated at different times between 1876 and 1902, restrictive laws known as Black Codes that severely limited black people’s movement, education, voting rights, and property ownership had passed in North Carolina’s General Assembly much earlier, in 1866. Reconstruction nullified, but did not eliminate, the practice of Black Codes. In 1875, with the assistance of Virginia-born attorney and educator John Mercer Langston (who had his portrait taken by Hugh Mangum not long before he died in 1897), Congress wrote and passed a Civil Rights Act. Aimed at protecting African Americans’ rights of citizenship, the law was never effectively enforced and did not cover public schools. After Plessy v. Ferguson, southern white politicians were able to revive the principles of the Black Codes, and in North Carolina, as elsewhere in the South, they soon passed laws, statutes, and ordinances that made i...