- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

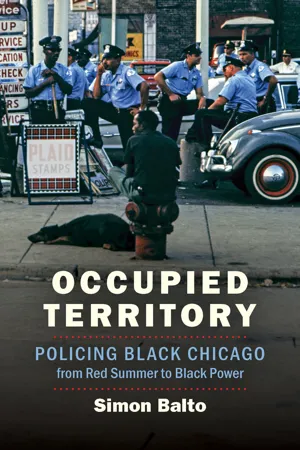

About this book

In July 1919, an explosive race riot forever changed Chicago. For years, black southerners had been leaving the South as part of the Great Migration. Their arrival in Chicago drew the ire and scorn of many local whites, including members of the city's political leadership and police department, who generally sympathized with white Chicagoans and viewed black migrants as a problem population. During Chicago's Red Summer riot, patterns of extraordinary brutality, negligence, and discriminatory policing emerged to shocking effect. Those patterns shifted in subsequent decades, but the overall realities of a racially discriminatory police system persisted.

In this history of Chicago from 1919 to the rise and fall of Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s, Simon Balto narrates the evolution of racially repressive policing in black neighborhoods as well as how black citizen-activists challenged that repression. Balto demonstrates that punitive practices by and inadequate protection from the police were central to black Chicagoans' lives long before the late-century "wars" on crime and drugs. By exploring the deeper origins of this toxic system, Balto reveals how modern mass incarceration, built upon racialized police practices, emerged as a fully formed machine of profoundly antiblack subjugation.

In this history of Chicago from 1919 to the rise and fall of Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s, Simon Balto narrates the evolution of racially repressive policing in black neighborhoods as well as how black citizen-activists challenged that repression. Balto demonstrates that punitive practices by and inadequate protection from the police were central to black Chicagoans' lives long before the late-century "wars" on crime and drugs. By exploring the deeper origins of this toxic system, Balto reveals how modern mass incarceration, built upon racialized police practices, emerged as a fully formed machine of profoundly antiblack subjugation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Occupied Territory by Simon Balto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Negro Distrust of the Police Increased

MIGRATION, PROHIBITION, AND REGIME-BUILDING IN THE 1920S

Horace Jennings lay in the street as Chicago convulsed. Acrid smoke hung in the air, mingling with the smells of an urban midsummer heat wave: the damp dirt and mud of unpaved streets; the sulfurous odors of manufacturing plants; the animal smells of the packinghouses. Furies raged. Around the city and particularly on the South Side, feet pounded the pavement, echoing hearts beating in chests. The day before, July 27, 1919, the threat of a Red Summer had become Chicago’s reality, unleashing one of the worst race riots the United States had yet known. White Chicagoans marauded through black neighborhoods. Black Chicagoans armed themselves. The city seethed.

Blood leaked from Jennings’s body, and pooled under his skin, where it would soon turn to bruises. Pain settled into his muscles and bones. He was alive, although with his nerves doubtlessly as racked as his body. A tide wave of racist violence had just cascaded over him, leveled by the hands and feet of a mob of white men.

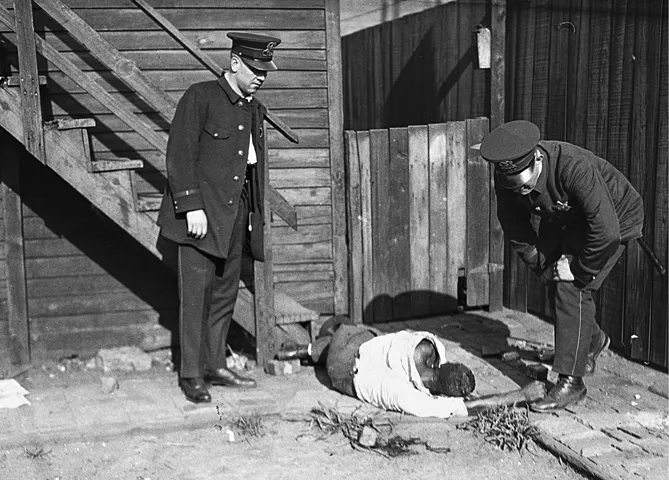

An officer with the CPD loomed over him. “Where’s your gun, you black son a bitch?,” the officer growled. “You niggers are raising hell.” Before Jennings could respond, his thoughts exploded under a crushing blow that hurled him into unconsciousness. When he woke again at Burnside Hospital, he discovered that the officer had stolen the money from his pockets.1

Across town, an unidentified man hurried toward police officers to plead for protection. The officers grabbed the man, searched him, and clubbed him with their blackjacks. Pulling free, the man ran. He didn’t get far. An officer leveled his gun and fired, and the man crumpled into a heap under the railroad tracks of an elevated train at Thirty-First and State. Above him, an eerie stillness descended where the trains should usually have clattered — the rage and fear enveloping Chicago had brought rail traffic to a stop.2 Below the quieted tracks, the officers retrieved the man’s body. Finding him still breathing, they took him to a holding cell for processing.3

Near the same El stop, William Thornton went looking for his mother, concerned about her well-being as Chicago descended into violence. He couldn’t find her. Abandoning his search, he asked a nearby police officer to help him get home and protect him from the white mobs. Instead, the officer escorted him to a police station, where he was tossed in a holding cell.

Another white police officer watched a mob beat and rob John Slovall and his brother. Wellington Dunmore suffered the same indifference — two policemen looked on as white men battered him. On his way to his job at the Union Stock Yards, William Henderson was besieged and badly beaten by a mob as he walked through Canaryville. When police arrived, they arrested Henderson but none of the members of the mob.4 Joseph Scott, meanwhile, was pummeled on a Chicago streetcar by twenty-five white men. After beating him within an inch of his life, the mob left. As Scott lay on the streetcar floor, a CPD officer peered in and ordered him to get out. The officer told Scott that he wanted to shoot him. He didn’t, but he did beat, push, and finally arrest him. Police neither questioned nor arrested any of the white assailants.5

Kin Lumpkin, trying to navigate the violence on his way to work at the stockyards, found himself cornered on the El platform at Forty-Seventh Street by still another white mob. The mob beat him ruthlessly, and a nearby police officer followed injury with insult, placing Lumpkin under arrest and charging him with rioting. Lumpkin spent four nights in lockup without contact with the outside world. The historical record doesn’t indicate where he was housed, but the options were unpleasant. Many lockups lacked sewage systems other than a floor-length trough through which rivers of piss, shit, and vomit ran. Most lacked toilet paper, and had bad lighting, worse plumbing, and neither beds nor bedding. More than a few were basement firetraps with rickety wooden stairs the only way out.6 And above all else, Lumpkin and black arrestees like him ran the risk of spending the hot days and humid nights of Chicago’s 1919 race war locked in close quarters with white men who loathed them.

It’s unlikely that these men knew each other, but history binds them together. The experiences they shared — in holding cells, on city streets, on and under the lines of the El — represent some of the most chilling abuses and the infuriating neglect that black people would experience at the hands of the CPD during those hellish days and nights in the summer of 1919. In an extreme crisis, men and women hoped for some level of kindness (or at least adherence to sworn duty) from the police officers they turned to for protection. All too often, what they received instead was ambivalence, vitriol, or violence.

Chicago police officers stand over a black victim of the 1919 riot. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-065480; Jun Fujita, photographer.

The 1919 riot is a cornerstone in Chicago’s history. It seared the city, leaving psychic scars that lingered in black Chicago’s collective consciousness for generations. It mangled beloved things, twisting the familiar into bitter symbols of racial ferocity. For the parents of Dempsey Travis, a community leader, water became freighted with terror. Travis remembered that his mother, stricken by the memory of the riot and its beachfront origins, “never put even a toe into Lake Michigan’s water” after that year. His father never wore a swimsuit again.7 Beyond the individual, it cohered the community. Chicagoan Chester Wilkins looked back on the riot as a moment when the black community realized it was on its own when facing danger. Decades later, he recalled that the riot had brought black Chicago “closer together than they had ever been before,” and demonstrated to them their need to arm and protect themselves.8

In particular, the riot is critical to the historical relationship between black Chicago and the police department. It was the most pitched interracial conflict that the city has ever known. Many of the black people who experienced it had come to Chicago on the promise of something better than what the Southland they’d left was willing to offer. And within the riot’s terrible violence, the police department revealed itself as an institution that would not work well for black people. Members of the CPD repeatedly proved themselves to be defenders of whiteness and the color line, rather than protectors of all life and livelihood. And black Chicagoans would not soon forget. A year after the riot’s violence had settled into détente, the Defender asked rhetorically: “Who among us does not remember how defenseless men and women of our group, innocent of any thought of wrongdoing, were dragged from their homes and incarcerated in dark and dingy cells?”9

The answer, of course, was that everyone remembered. And such memories of a police force unresponsive to black needs and often explicitly hostile to black people would be buttressed and bolstered in the years that followed. This chapter begins with the 1919 riot, but it moves outward through the 1920s, too, tracing several phenomena: police repression within black Chicago, made most acutely manifest in disproportionate arrest rates and grotesque violence; the unsafety black people felt in the face of white violence, with CPD officers frequently operating as racial partisans rather than public servants in moments of interracial conflict; and law enforcement and political operatives actively participating in the undermining of social stability in black neighborhoods by colluding with organized criminal elements.

It also explores the derogation of black people’s rights to influence this system, hampered as they were by the mechanisms of patronage politics and suggestive of the limited harvests that black electoral power actually yielded. It is not that the police department could not or would not change. Indeed, by the end of the 1920s, the CPD was proving itself entirely open (at least in theory) to change. But the changes wrought flowed from the activism of white elites trying to guide it toward a more assertive tough-on-crime approach. Black people — those with the most vested interests in seeing the department remolded — were left out in the cold when these conversations took place.

The policing apparatus was not yet a fully formed instrument of antiblack repression. But the baseline represented by 1919 is important. In this moment, black people were not yet a sizable enough population to preoccupy the crafters of police policy, and there was little intentionality that guided public policy toward them. But neither was the police force an instrument that allowed black people fairness or justice. Some black Chicagoans would fume about the police’s failure to ensure black safety from racial violence and to eradicate elements from their neighborhoods that they saw as undesirable. Others, beaten by nightsticks or shaken down on the street, would claim discriminatory harassment. Meanwhile, some articulated this as a better age — a hanging moment in time before police-community relationships fell from a precipice. Yet even those in the last camp — who recalled this as a period of general quiescence, as the educator and community historian Timuel Black did — still characterized the relationship as “racial, not brutal.”10 Which is not precisely a ringing endorsement.

Furies and Heat: Chicago’s Riot Era

Lake Michigan forms Chicago’s gorgeous eastern edge. From the shore, it appears as a seemingly endless, unbroken mass of water. When the sun comes up, it appears to rise from the depths of the water itself. As first light creeps across the lake, on particularly hot days, this combination of moisture and sun creates a haze. Humidity dampens the air and skin becomes sticky; the city shimmers with heat. July 27, 1919, was that kind of day. And under the haze of an ordinary, hot Chicago summer day, the city erupted. The explosion, many people would later lament, was ignited by a policeman who wouldn’t do his job.

Police officer Daniel Callahan stood at the Twenty-Ninth Street Beach on Chicago’s South Side. By midday, it was unbearably hot, and bodies packed the city’s beaches. On such days, the CPD posted officers to the lakefront to ensure that the thousands of swimmers and sunbathers remained orderly. Not all of them were well equipped for the job. Daniel Callahan was a temperamental man, and it’s doubtful that standing on the beach in full uniform in hundred-degree heat improved his general mood. He stared out across a mass of people, all white, since Chicago’s beaches were segregated — informally, but rigidly.

When it came to beaches, black peoples’ “place” was two hundred yards north, just east of where Twenty-Fifth Street dead-ended. That day, seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams and three friends pushed a raft out from the shallows of the “Hot and Cold,” a little island just off the shore. Paddling out, the boys hoped to tie up at a post farther out in the lake, where they could dive and swim. But Lake Michigan’s currents are unpredictable. The boys’ raft got carried south, past the manmade breakwater that marked the northern edge of the white beach. And the sight of a raft of black boys floating into white waters enraged people on Twenty-Ninth Street. A man named George Stauber began hurling rocks — stone after stone raining down on and around the raft and the boys clinging to it. Amid the hailstorm, Eugene Williams went under. By the time divers reached him, he was dead.11

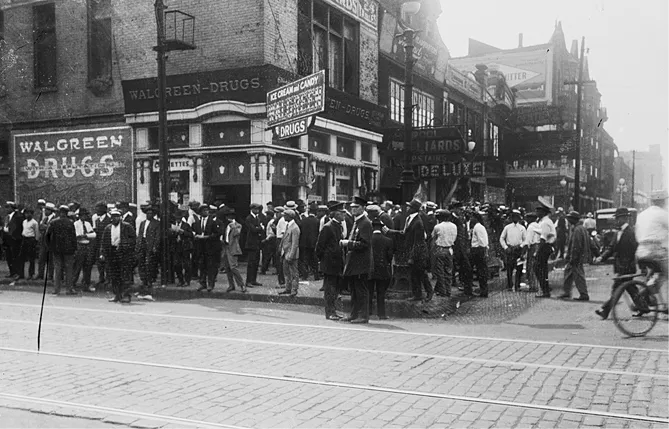

A crowd of black men gathers on the South Side during the 1919 riot. DN-0071297, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum.

Williams’s friends scrambled to shore, pointing Stauber out to a black policeman, who approached to question him. Officer Callahan intervened, telling his black colleague not to make the arrest, typical of the racial rank-pulling that black officers frequently had to reckon with.12 Williams’s friends pleaded. Crowds gathered. But Callahan refused to see Stauber arrested, and a short while later, he turned around and arrested one of the men shouting for Stauber’s arrest. Furious, black citizens swarmed Callahan. A riot, the CCRR noted later, “was under way.”13

Beyond the sheer horror of Eugene Williams’s death, Officer Callahan’s actions and inactions in the midst of Williams’s killing were the riot’s clearest accelerant, so blame churned his way. The Broad Ax, one of Chicago’s black newspapers, would later write hyperbolically that the situation “would have been ten million times better for all the citizens of Chicago” if Callahan had “discharged his sworn duty and promptly arrested the white person who struck Eugene Williams.”14 The CCRR, in its assessment two years after the riot, wrote that “the drowning and the refusal to arrest, or widely circulated reports of such refusal, must be considered together as marking the inception of the riot. … There was every possibility that the clash, without the further stimulus of reports of the policeman’s conduct, would have quieted down.”15 That impression was corroborated by Callahan’s own police chief, John Garrity, who temporarily suspended Callahan, saying: “If these charges [of refusal to arrest] are true, I believe Callahan is responsible for this outrageous rioting.”16

For his part, Callahan was perfectly willing to play the villain. Interviewed shortly after being reinstated by the CPD, Callahan was without remorse: “So far as I can learn the black people have since history began despised the white people and have always fought them. … It wouldn’t take much to start another riot, and most of the white people of this district are resolved to make a clean-up this time. … If a Negro should say one word back to me or should say a word to a white woman in the park, there is a crowd of young men of the district, mostly ex-service men, who would procure arms and fight shoulder to shoulder with me if trouble should come from the incident.”17

Thirty-eight Chicagoans died in the riot, and more than five hundred others suffered injury. Over a thousand more were rendered homeless. Responsibility extended far beyond one man, but the bloodletting began with Callahan.

Outward from the lakefront, the violence exploded across the South Side. Two hours after Eugene Williams’s corpse was pulled from Lake Michigan’s waters, a policeman’s bullet struck down James Crawford, a black man, after Crawford allegedly fired a gun into a mass of police officers. In the black districts near the be...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Overpoliced and Underprotected in America

- Prologue: The Promised Land and the Devil’s Sanctum: The Risings of the Chicago Police Department and Black Chicago

- 1. Negro Distrust of the Police Increased: Migration, Prohibition, and Regime-Building in the 1920s

- 2. You Can’t Shoot All of Us: Radical Politics, Machine Politics, and Law and Order in the Great Depression

- 3. Whose Police?: Race, Privilege, and Policing in Postwar Chicago

- 4. The Law Has a Bad Opinion of Me: Chicago’s Punitive Turn

- 5. Occupied Territory: Reform and Racialization

- 6. Shoot to Kill: Rebellion and Retrenchment in Post–Civil Rights Chicago

- 7. Do You Consider Revolution to Be a Crime?: Fighting for Police Reform

- Epilogue: Attending to the Living

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index