- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conquered by Larry J. Daniel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Flawed Foundations

The Provisional Army of Tennessee

The beginning of the Army of Tennessee was the Tennessee state army, the so-called Provisional Army of Tennessee, under the titular leadership of Governor Isham G. Harris. It was the state army that became the genesis of the Confederate army. From its inception, there were cracks in the foundation.

Political clout, slave power, and personal friendship to the governor became the typical gateways to a military commission. Desiring to reach beyond his Democratic base and cultivate the proslavery Whigs, Harris gave the two major general appointments to Democrats, but four of the five brigadier commissions went to Whigs. The appointments of the major generals—Gideon Pillow of Memphis and Samuel R. Anderson of Nashville—did not come as a surprise. Pillow, a two-time vice-presidential aspirant, Mexican War veteran, large slaveholder, and ardent secessionist, had an eight-year association with Harris. He unquestionably had a dark side, being jealous, egotistical, and vengeful. Anderson was the fifty-seven-year-old president of the Bank of Tennessee. He had combat experience, having served as lieutenant colonel of the 1st Tennessee during the Mexican War.1

The five brigadiers included Benjamin F. Cheatham, the foul-mouthed, hard-drinking proprietor of the Nashville Race Track; sixty-five-year-old Robert C. Foster, a Franklin attorney, longtime member of the Tennessee General Assembly, and veteran of the Mexican War; forty-one-year-old state attorney general John L. Sneed; an old friend of Pillow’s, William R. Caswell of East Tennessee, who, like Sneed, was a captain in the 1st Tennessee cavalry during the Mexican War; and Felix Zollicoffer, a former U.S. senator and Nashville newspaper editor. The Confederate government subsequently granted brigadier commissions to Pillow and Anderson but only reluctantly granted commissions to Cheatham and Zollicoffer.2

In his efforts at political inclusiveness, Harris had snubbed West Pointers, granting them only support positions. Daniel Donelson became adjutant general; Bushrod Johnson, chief engineer; John P. McCown, A. P. Stewart, and Melton A. Hayes headed the fledgling artillery corps; and Richard G. Fain, who had quit the army upon graduation to become a Nashville merchant, became commissary general. Twenty-five-year-old Capt. Moses H. Wright, who had previously served at the Watervliet and St. Louis Arsenals, would lead the Ordnance Bureau. Only McCown and Johnson had any combat experience. McCown had no connection to Harris (he would grow to detest him) and had gone through an embarrassing court-martial incident. Marshall Polk, another West Pointer, commanded a Memphis battery. Five other Tennessee West Pointers—John Adams, Henry Davidson, William H. Jackson, James A. Smith, and Lawrence Peck—had not resigned their U.S. commissions at the time of the state army formation. Andrew Jackson III, grandson of Andrew Jackson, joined the Confederate army before the firing on Fort Sumter. Donelson, the most senior of the West Pointers, had served in the Regular Army only six months before resigning his commission.3

Several of Harris’s appointments went to civilians with little or no military background. Forty-nine-year-old Vernon K. Stevenson, founder of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, became quartermaster general. The job dealt with contracts and finances, so the appointment seemed reasonable. There may have been another reason: Stevenson was widely rumored to be a possible Democratic candidate for governor in the fall, and Harris may have wished to clear the field for his second run. Also in the Quartermaster Department was George W. Cunningham, a forty-year-old Warren County merchant. Dr. Benjamin W. Avent, a highly respected forty-eight-year-old Murfreesboro physician, was tapped as the army’s medical director. William H. Carroll, the Nashville postmaster general and son of a former governor, became inspector general. Those who knew him dismissed him as a stupid drunkard who could be easily controlled.4

Politics and position influenced the top appointments, but Tennessee simply lacked the military tradition of Virginia. Of the West Pointers in the state army, only two would distinguish themselves in the Army of Tennessee—Johnson and Stewart. Perhaps even more serious was the fact that there was an even greater dearth of professionally trained officers at the level of colonel. Of the 135 men who would rise to the rank of colonel in Tennessee, excluding Andrew Jackson III, none had attended West Point and only four had graduated from private military academies. In comparison, sixteen West Pointers served as Virginia colonels, fifty-seven from the Virginia Military Institute, two from the U.S. Naval Academy, and seven from private military academies. Even the Virginia Military Institute graduates living in Tennessee proved to be a remarkably undistinguished lot. Eight of the Tennessee colonels had backgrounds in the militia, which were worth little, and nineteen had combat experience in the Mexican or Seminole War. Wealth and prominence served as the basis for the appointments of most of the Tennessee colonels—there were nine physicians and forty lawyers.5

The provisional army was also logistically handicapped. Initially, the state arsenal housed only 8,761 arms, almost all old flintlocks. Practically speaking, the entire lot proved worthless, at least until the arms could be altered to percussion. In late April 1861, Louisiana governor Thomas O. Moore shipped to Memphis 3,000 arms and 300,000 rounds of ammunition, all from the captured U.S. arsenal at Baton Rouge. The governors of Mississippi and Arkansas also offered sixteen old field guns. Additional boxes of ammunition arrived from Baton Rouge, followed by two carloads of small arms from Richmond, Virginia. In May, the Confederate secretary of war, LeRoy Walker, released 4,000 muskets to Tennessee, but there were strings attached; they could only be issued to regiments joining the Confederate service. Already three such regiments had been transferred to Virginia. Harris pleaded with Walker to relax the policy but to no avail. Pillow subsequently stopped 3,000 flintlock muskets passing through Memphis on the way to Mobile, Alabama. The general’s alarmist language convinced Walker to issue 1,200 of the lot to Tennessee troops. By state count, there were 5,000 percussion muskets in Memphis and 3,000 in Nashville by May 12. Authorities encouraged volunteers to show up with hunting rifles and shotguns. Although the press boasted that 75,000 such firearms existed, officials estimated that only 4,000 could be gathered. Pillow claimed that he could put 25,000 men in the field if he could only arm them.6

The men were trained in camps of instruction, such as Camp Brown at Union City and Camp Trousdale in Middle Tennessee, four miles from the Kentucky border. Small until drills occurred, but camp social life seemed to be the order of the day. James Hall, writing from Camp Brown, told his wife, “We see ladies and little girls in camp every day, who come to see the soldiers.” “H,” also at Union City, described it thus: “We are having a gay time of it here. We are visited every day by the ladies of the neighborhood, and also by the ladies of Jackson, Tennessee.” U. G. Owens wrote similarly: “Several big dances every night, great excitement all the time, amusement of every kind on earth you could think of. Great many ladies visit us from the country dance etc.” At Camp Trousdale, John Goodner declared, “We have a great many lady visitors here every day from all of the towns around the adjoining counties.”7

The soldiers, itching for a fight, remained mystified why, for months, nothing happened. The bugler of the 154th Tennessee, camped at Randolph, was told to practice the call for a general alarm. Through a misunderstanding, he sounded the alarm in camp. Rumors quickly spread that enemy gunboats were approaching. “The camp was in a blaze of excitement and the soldiers panted for the opportunity to display their valor.” Writing from Camp Trousdale, Matthew Buchanan candidly remarked, “I wish we had the thing over & had arms and orders to pitch into the Yankees.”8

William H. Russell, a war correspondent for the London Times, viewed some of the fortifications along the Mississippi River during the summer. While some regiments, such as the 154th Tennessee, had uniforms and firm discipline, others were ill clad and simply lay around camp. The officers, mostly lawyers, merchants, and planters, were entirely ignorant of drill. Russell noticed that the men awkwardly handled their muskets; indeed, many carried only sticks. When one of the heavy artillery pieces was test-fired, it leaped off the carriage, leaving Russell to believe that it was safer being near the target than on the gun crew. When 800 men lined up for inspection, Pillow offered a brief speech on courage. A staff officer shouted, “Boys, three cheers for General Pillow.” One wag shouted back, “Who cares for General Pillow?”9

Discipline continued to be a problem. In Polk’s Tennessee Battery, a man by the name of Holman kept skipping roll call. The captain warned him several times but to no avail. When he missed again, Holman was ordered to mark time for an hour. “He seemed surly,” Captain Polk told his wife. “I ordered my guard to charge bayonets. One of them hesitated. I sprang up saber in hand, not drawn, told him that this was no child’s play we were engaged in and ordered him to bring down his gun. He obeyed; I then told Holman to mark time, which he did. The men of Douglas’ regiment [9th Tennessee] collected outside my sentinels & I saw trouble was brewing. Merely wishing to make an example I had intended to let the man off as soon as he obeyed[;] but seeing them and hearing their remarks I determined he should mark his sixty minutes or die.” Polk’s officers and men stood by him while he remained seated with pistol concealed, fully intending to shoot the first man who crossed his line. A colonel and several captains came up and dispersed the mob. The men grumbled loudly about the captain, some of them claiming that he treated them “like they were negroes.” Cheatham threatened to call out the entire brigade if the 9th continued its rebellion.10

It did not take long for sickness, mostly measles and diarrhea, to ravage the camps. The lack of preparedness and supplies became apparent. A report in the Tennessee Baptist criticized the makeshift arrangement of a Nashville hospital. The cots were so jammed together that it proved almost impossible to walk between them. The reporter wondered if generals or colonels would be allowed to lie unattended in such filth. One patient noted: “There were several of us together, and all the bunks being occupied, we had to sleep on the floor by the stove. There were 250 men in that room, their bunks all arranged in rows. A chill ran over me at seeing so many pale faces by gas-light.”11

In the early days of its formation, the Army of Tennessee was thus crippled in leadership, preparedness, and discipline. The lack of professional officers and noncommissioned officers resulted in inadequately trained troops, looser organization, and lax administration, all of which resulted in a less pronounced discipline. The army would eventually emerge from these baked-in flaws, but it would take time.12

The Influence of Sectionalism

The army soon grew beyond the original Tennessee core. Richard McMurry recognized that the Army of Tennessee was more western than the Army of Northern Virginia was eastern. In late 1862 (based on battalions, batteries, and regiments), Robert E. Lee’s army counted 61.6 percent of its men from eastern states, 19.5 percent from central states (Georgia and Florida), and 17.6 percent from western states. The lack of an eastern presence, specifically Virginians, robbed the Army of Tennessee of the “mythical aura” of Virginia, and thus affected morale, argued McMurry. When categorizing is done by the actual number of infantry present, however, rather than the number of units (which varied widely), the difference is even more stark. In March 1863, the state-by-state breakdown of the Army of Tennessee’s infantry was as follows: western, 90 percent; central, 6 percent; and eastern, 4 percent.13

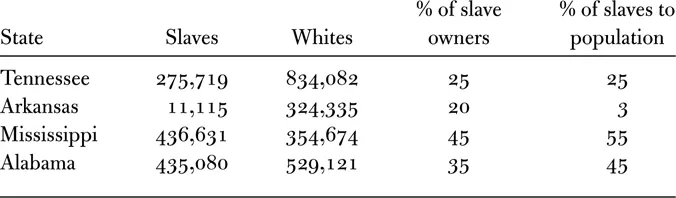

A “more western” army, though on the surface more homogeneous, did not equate to more harmonious. The western theater, that expanse between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River, was divided into three major sections—the Upper South, the Lower South, and the Highlands. Precisely why soldiers had trouble identifying with troops from other sections was complicated. According to a Nashville paper, it was partially grounded in the “petty bigotry and partisan vindictiveness” of politics. Mark Weitz claimed that the South was dominated by localism. Different regions meant different geography and climate, which meant different crops (cotton versus food production), which in turn meant different means of subsistence, which resulted in variant lifestyles and cultures.14 Sectionalism, especially between the Upper South and Lower South, was grounded in antebellum society and the population distribution of slavery.

Lower South states, the so-called cotton states, had been among the original seven seceding states, whereas Upper South states had shown a more conservative reluctance toward secession. A perception, untrue to be sure, emerged that Lower Southerners represented the cotton aristocracy, while Upper Southerners were undisciplined, knife-toting backwoodsmen, less loyal to the Cause. To be sure, the Upper South was far from a cavalier, planter society. Political differences per se in the Army of Tennessee did not revolve around party politics but rather commitment to secession. Tennessee and Kentucky had supported the moderate Constitutional Union Party in the 1860 election. Lower South troops thus cast a suspicious eye on the latecomers to secession.

TABLE 1. Population distribution of slavery in the South

The question of the commitment of Upper South soldiers came into play at the fall of Fort Donelson in February 1862. Some 10 percent of the Southern captives, 1,640, took the oath of allegiance shortly after arriving in the North. The overwhelming majority of these came from the Upper South. Indeed, the majority came fro...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures, Maps, & Tables

- Preface

- 1. Flawed Foundations: The Provisional Army of Tennessee

- 2. Losing the Bowl: Savior of the West?

- 3. High Tide: Bragg Takes Command

- 4. The Officer Corps: The Bragg Influence

- 5. The Army Staff

- 6. The Stones River Campaign: Neck-and-Neck Race for Murfreesboro

- 7. Confrontation: Intrigue

- 8. The Decline of the Cavalry: The War Child

- 9. The Manpower Problem

- 10. The Brotherhood

- 11. The Sway of Religion

- 12. The Middle Tennessee Debacle: The Federals Begin Probing

- 13. Missed Opportunities: All Were Misled

- 14. Great Battle of the West: Chickamauga, the Battle Begins

- 15. The Medical Corps

- 16. Logistics

- 17. The Road Off the Mountain: Wheeler’s Raid

- 18. The Johnston Imprint: Finding a Replacement

- 19. Cleburne, Blacks, and the Politics of Race

- 20. Home Sweet Home

- 21. Struggle for Atlanta: Dalton to Resaca

- 22. A Pathway to Victory: The Fog of War

- 23. Conquered: North Georgia Campaign

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index