- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Invention of the Favela

About this book

For the first time available in English, Licia do Prado Valladares’s classic anthropological study of Brazil’s vast, densely populated urban living environments reveals how the idea of the favela became an internationally established—and even attractive and exotic—representation of poverty. The study traces how the term “favela” emerged as an analytic category beginning in the mid-1960s, showing how it became the object of immense popular debate and sustained social science research. But the concept of the favela so favored by social scientists is not, Valladares argues, a straightforward reflection of its social reality, and it often obscures more than it reveals.

The established representation of favelas undercuts more complex, accurate, and historicized explanations of Brazilian development. It marks and perpetuates favelas as zones of exception rather than as integral to Brazil’s modernization over the past century. And it has had important repercussions for the direction of research and policy affecting the lives of millions of Brazilians. Valladares’s foundational book will be welcomed by all who seek to understand Brazil’s evolution into the twenty-first century.

The established representation of favelas undercuts more complex, accurate, and historicized explanations of Brazilian development. It marks and perpetuates favelas as zones of exception rather than as integral to Brazil’s modernization over the past century. And it has had important repercussions for the direction of research and policy affecting the lives of millions of Brazilians. Valladares’s foundational book will be welcomed by all who seek to understand Brazil’s evolution into the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Invention of the Favela by Licia do Prado Valladares, Robert N. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

GENESIS OF THE RIO FAVELA

From Country to City, from Rejection to Control1

Favelas, now seen as a typically urban phenomenon, were viewed during the first half of the twentieth century as a veritable “rural world in the city.” This chapter analyzes the early representations of these spaces in Rio de Janeiro, where they have existed now for over a hundred years.2 I argue that the dominant representations of the favela in the second half of the twentieth century broadly depended on those of the first decades of the century and that these representations organized a founding myth of the favela’s social representation.

By reviewing nonspecific literature on the topic, I will stitch together notes and information that confirm the favela’s growing importance in the social imaginary and show how this social construction of representations of the favela occurred. This happened at a time when knowledge and action were inseparable, and the concerns of the intelligentsia, both local and national, were centered on the future of the young republic—on the health of society, on the hygiene of the country, and on the beautification of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

This multiplicity of views and interpretations—a legacy of journalists, medical doctors, engineers, and urban planners who wrote even before the social sciences came on the scene—attests to the representations, associations, images, and vocabulary used at various times by diverse social actors.

Taken as a whole, the bibliography of writings about the Rio favela suggests a periodization, widely disseminated, of relations between the state and the favela, and between the latter and the various political regimes peculiar to each period. This evolution may vary according to the authors,3 but it is generally broken into the following stages: (1) the 1930s—the beginning of the process of favelization of Rio de Janeiro and the recognition of the favela by the 1937 Código de Obras (Building Code); (2) the 1940s—the first proposal of public intervention, leading to the creation of the Proletarian Parks during the Vargas era; (3) the 1950s and the early 1960s—uncontrolled expansion of favelas under the populist aegis; (4) from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s—the elimination of the favelas and removal of their residents during the authoritarian regime; (5) the 1980s—urbanization of the favelas by the BNH and by the social service agencies after the return to democracy; (6) the 1990s—urbanization of the favelas by means of Rio de Janeiro’s policies and the Programa Favela-Bairro (Favela to Neighborhood Program).

My intent is to reconstruct the evolution of the representations of this social space based on landmarks and monuments that are exceptions to the generally used periodization. In other words, the history of reflection on the favela should not be confused with the history of the favela properly speaking, based on dates, events, and sociohistorical conditions, characterized moreover by various actions or interventions implemented by governments in distinct political and administrative moments.

Based on a reading that does not follow established historiography, I propose a break with the traditional periodization without wholly discarding it. To this end, I propose a sociology of the sociology of the favela that examines the origins and constitution of learned thought about this social phenomenon, privileging its actors, connections, interests, representations, and actions.

The history of reflection on the favela here follows another logic, and its periodization is constituted on the basis of a myth of origin: the image of the settlement of Canudos described by Euclides da Cunha in Os Sertões (1902; published in English as Backlands: The Canudos Campaign, 2010). This is an image that corresponds to those glimpsed by the first visitors to the favela in Rio, when they transposed their descriptions of the duality coast-versus-backlands to the duality city-versus-favela.

Following this period of discovery comes a second moment of transformation of the favela into a social and urban planning problem, followed by a third period, in which an administrative approach to the problem takes the shape of concrete measures and policies. A fourth period relates to the production of official data by way of the 1948 census of the favelas of the Federal District and the General Census of 1950, which generalized the definition of this sort of urban residential cluster.

When the social sciences came on the scene, other periods followed. In this chapter, however, I intend to consider only the first four periods, with the goal of pointing out the representations that inspired the social sciences or that, not always consciously, they inherited.

THE LITTLE-KNOWN HERITAGE OF THE CORTIÇO AND MORRO DA FAVELLA

Neither in Europe nor in Brazil were the social sciences at the roots of the “discovery” of poverty (Leclerc 1979; Himmelfarb 1984; Bresciani 1984; Barret-Ducrocq 1991; Valladares 1991). In the nineteenth century, when urban poverty became a concern of European elites, it was professionals in the press, literature, medicine, law, and philanthropy who came to describe poverty and propose measures to fight economic misery. This knowledge was used to a practical end: to understand, to indict, and to act; that is, knowledge was for proposing solutions, for ministering to and managing poverty and those affected by it. And so science placed itself at the service of reason, of urban order, and of the health of urban populations.

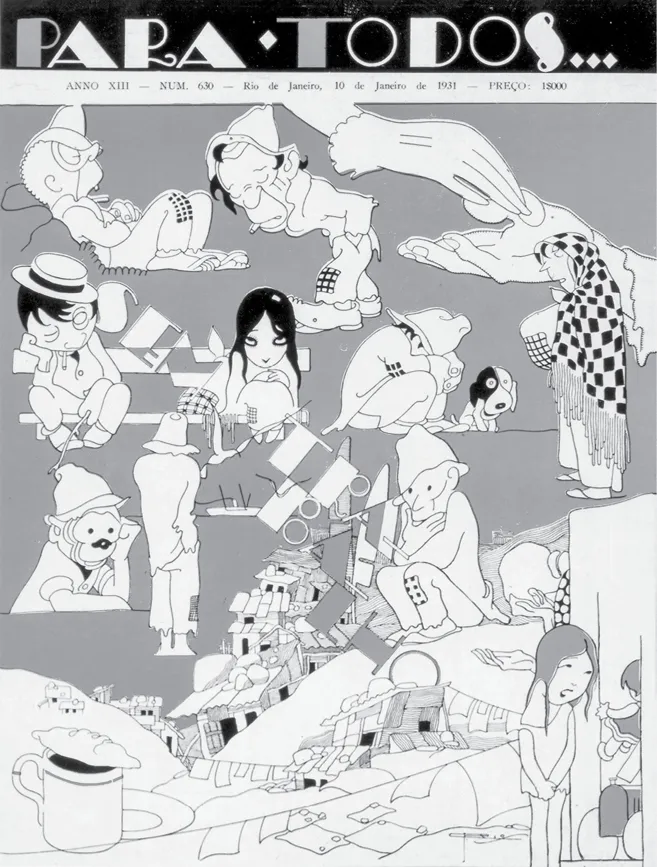

In Rio de Janeiro, as in Europe, those first interested in portraying the urban scene and its characters in detail turned their gaze to the cortiço, or tenement.4 As the locus of poverty par excellence in the nineteenth century, these were residences inhabited both by workers and by vagabundos (bums) and malandros (hustlers)—members of the so-called dangerous class. Defined as a “social hell,” the tenement was seen as the gateway to idleness and crime, as well as an environment that favored epidemics. It was thus cast as a threat to social and moral order. As a space believed to propagate disease and vice, it was denounced and condemned through medical and hygienist discourse, which led city governments to adopt administrative measures.5 Figure 1, a caricature by J. Carlos, confirms this negative image of the world of the poor, present in Rio de Janeiro since the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth century.

In Rio de Janeiro, laws were passed to block the construction of new tenements.6 At the end of the nineteenth century, a veritable war was unleashed, leading to the demolition of the most important cortiço, Cabeça de Porco (Pig’s Head). Later, Francisco Pereira Passos, mayor of Rio from 1902 to 1906 and known as the “Tropical Haussmann,”7 became the great agent of urban social reform. One of his principal goals was to sanitize and civilize his city by eradicating countless dwellings of the poor.

Studies of the Rio de Janeiro tenements show that this type of residence could be considered the “seed” of the favela. According to a study by Lillian Fessler Vaz (1994, 591), the Cabeça de Porco tenement, destroyed by Mayor Cândido Barata Ribeiro in 1893, had shacks and precarious dwellings of the sort identified in Morro da Providência (later Morro da Favella). Other authors also established a direct connection between the demolition of tenements in the city center and the illegal settlements in the hills in the early twentieth century (O. Rocha 1986; L. Carvalho 1986; Benchimol 1990).

Figure 1. “Typical Personages of the Idle Poor” (from Revista para Todos, no. 630, January 1931, Archive of Eduardo Augusto de Brito e Cunha).

It was only after this iron-fisted campaign against the tenement that interest was awakened in the favela as a new geographic and social space and the most recent territory of poverty. From the beginning, such interest was directed toward a certain favela that catalyzed everyone’s attention. This was Morro da Favella, which had already existed under the name Morro da Providência, and which earned its place in history through its connection with the Canudos Campaign. Former campaign combatants took up residence there, with the goal of pressuring the Ministry of War to pay their back salaries. Gradually, the name of Morro da Favella was extended to any group of shacks clustered without a street plan or access to public services, on invaded public or private land. These clusters began to multiply in the center and the North and South Zones of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

According to Maurício de Almeida Abreu, who researched the newspaper Correio da Manhã between 1901 and 1930, it was only in the second decade of the twentieth century that the word “favela” became a generic noun no longer referring just to Morro da Favella.8 A new category thus arose to designate a poor urban habitat of illegal, irregular settlement, without regard to norms, and generally on hillsides.

It is important to note that the phenomenon of the favela existed before it appeared as a category. The occupation of Morro da Providência dates from 1897. In 1898, Morro de Santo Antônio showed signs of a similar favelization process. According to Abreu and Lillian Vaz (1991), soldiers from another battalion returning from the same Canudos Campaign built shacks—with authorization from military chiefs—on Santo Antônio Hill, between Evaristo da Veiga and Lavradio Streets in central Rio. In 1898, a member of a hygiene commission pointed out the disturbing development of shacks in an already occupied area, while in 1901 the press denounced “the development of a completely new neighborhood, built without permission from municipal authorities and on property belonging to the state. … It contains a total of 150 shacks … and about 623 inhabitants” (Jornal do Commercio, 14 October 1901, qtd. in M. Abreu 1994b, 37).

The favelas of Quinta do Caju, Mangueira,9 and Serra Morena also date from the nineteenth century, all before Morro da Favella. Occupation of these areas began in 1881, and nothing proves that they were the result of illegal settlement. In the cases of both Quinta do Caju and Mangueira, the first inhabitants do not appear to have been from the Brazilian countryside. They were Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian immigrants, leading one to suppose that their settlement in these areas was authorized.10 Notwithstanding, it was Morro da Favella that went down in history. Already by 1900, the Jornal do Brasil proclaimed it to be “infested with vagrants and criminals that are shocking to families.” According to Marcos Luiz Bretas (1997, 75), a police officer pointed out in his report that “even though there are no families in the designated locale, it is impossible to do policing there because in this locale, which is a focal point of deserters, thieves, and common soldiers, there are no streets, the hovels are built of wood and covered with zinc roofs, and there is not a single gas outlet on the entire hill.”

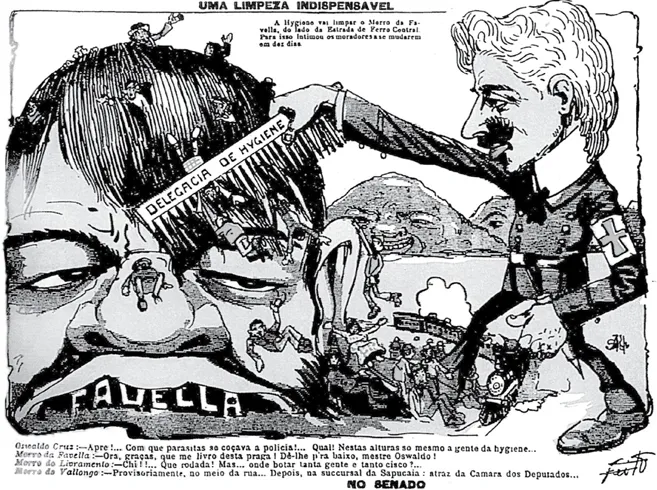

Figure 2. Oswaldo Cruz sanitizing Morro da Favella (Oswaldo Cruz Monumenta Histórica, vol. 1, no. 188).

Morro da Favella, which was photographed as early as the first decade of the twentieth century, not only drew considerable attention but also gave rise to initiatives by authorities, such as the sanitation campaign of 1907, under the direction of Oswaldo Cruz,11 illustrated in important caricatures published in the press.12

A caricature in the magazine O Malho (fig. 2) shows Oswaldo Cruz well-dressed, wearing shoes, with hair combed, bearing a Red Cross armband on his left arm, while, with his right hand, he sweeps the population out of Morro da Favella, with a comb that reads “Hygiene Police.” Morro da Favella is represented by the head of man with a surly expression, perhaps even with the look of an evildoer. The image suggests that the inhabitants are as lice to be removed. A short text accompanies the caricature: “An indispensable cleaning: Hygiene will clean Morro da Favella, next to the Central Railway. For this reason, the residents were told to move within ten days.”

In the early decades of the twentieth century, journalists, engineers, medical doctors, and public figures connected with management of the capital, including chiefs of police, gradually lost interest in the tenements, which became “a thing of the past,” of less importance for hygienism. The tenements survived only residually.

The favela then came to occupy first place in the debates about the future of the capital and of Brazil itself. It became the object of discourse of hygienist doctors who condemned the unhealthy dwellings. The ecological premise that the environment conditions human behavior was applied to the favela, and the perception persisted that the poorer classes were responsible both for their own ills and those of the city.13 This leads one to see that the debate about poverty and the environment of the poor, which had stirred up the local and national elites since the nineteenth century, would give rise to specific thinking about the Rio favela.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE MYTH OF ORIGIN: EUCLIDES DA CUNHA, CANUDOS, AND THE RIO FAVELAS

The process of constructing social representations of the favela began with descriptions and images that were left to us by writers, journalists, and social reformers at the beginning of the twentieth century. Their writings, widely distributed at the time, caused a collective imaginary to develop about the microcosm of the favela and its residents, at the same time that they set up the opposition between favela and city.

Although they belonged to differing ideological and political schools of thought and pursued distinct objectives in their visits to the hillsides, these writers shared a view of what these areas and their residents represented in the context of the federal capital and the young republic. Their points of view referred to a group of conceptions to the same world of values and ideas. Their representations converged to establish an archetype of the favela, a different world that emerged on the Rio landscape, against the current of the established urban social order.

To better understand this process, we must attend to a series of questions: What was the common origin of this understanding? Why did a certain view become consensual? And why did such a social construction attach itself to a myth, referred to by practically all of the authors who spoke of the favela at the beginning of the twentieth century—the myth of Canudos?14

Reading the texts from beginning of the century leads one to associate Morro da Providência, in Rio de Janeiro, with the town of Canudos, in the backlands of the state of Bahia. In fact, the two histories overlap, since it was the former federal combatants in the Canudos Campaign who settled in Morro da Providência, thereafter called Morro da Favella. Most of the commentators present two reasons for this change of name: (1) the favela plant, which had given its name to Morro da Favella in Canudos, was also found in the vegetation that covered Morro da Providência,15 and (2) the fierce resistance during the Canudos war of the entrenched fighters on the Bahian Morro da Favella, which had slowed the final victory of the Army of the Republic (the army’s taking of this position was decisive in the battle).

If the first explanation speaks to a physical similarity, the second has a powerful symbolic connotation that suggests resistance, the struggle of the oppressed against a powerful and dominating adversary. In Rio de Janeiro, the demobilized soldiers of the Canudos Campaign settled Morro da Providência, a strategic position in relation to the War Ministry, in hopes of receiving their overdue payment.

The mark of Canudos on this founding moment is quite evident. What I intend to demonstrate, however, is that Canudos’s mark on the Rio favelas’ myth of origin was more than a simple allusion to the Bahian town and the final battle. It also incorporated additional elements from the account of the campaign by Euclides da Cunha in Os Sertões (see note 14).

Considered Brazil’s “number one book” (R. Abreu 1998), with more than thirty editions in Portuguese—the first in 1902, the second in 1903, and the third in 1905 published by Edições Laemmert—Os Sertões was read by virtually every intellectual of the t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Deciphering the Favela

- Preface to the English-Language Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Note from the Translator

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Genesis of the Rio Favela: From Country to City, from Rejection to Control

- 2 The Shift to the Social Sciences

- 3 The Favela of the Social Sciences

- 4 Conclusion: The Favela, the Web, and the Census—A Disconcerting Reality

- Epilogue

- A Chronology of the Rio Favela

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index