![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Biography of a National Meal

The English Breakfast is the best-known national meal in the world, a unique cultural and culinary symbol of England and Englishness, in edible form. As Countess Morphy (1936) put it: ‘Breakfast is the English meal par excellence. . .one of the great national institutions of England’. But how did it attain this distinction, what can a national meal tell us about the nation that eats it, and is there more to the English breakfast than bacon and eggs?

This is a biography of the English Breakfast, a culinary detective story and a cookbook, rolled into one. It presents the history of the English Breakfast, the myths that surround it, the social changes that shaped it, and the enduring sentiments and appetites it evokes, concluding with a collection of authentic Victorian and Edwardian recipes for many forgotten delights of the breakfast table and sideboard from the heyday of this greatest of all meals.

* * *

In 1933, the food writer Robin Douglas gave a lyrical account of returning to England following a holiday in France. After crossing the English Channel on the night ferry, he drove through the Sussex countryside on a perfect day in late spring, until the ‘the most delicious smell in the world, a blend of wallflowers, warm earth, frying bacon and coffee’ drew him into the typically English welcome of breakfast at a roadside inn. For Douglas, as for countless others, the English Breakfast was both the symbol and substance of home, its aroma the very essence of England.

The English Breakfast is served on the small mountain trains that climb the Swiss peaks to resorts like Klosters where the English pioneered winter sports. It is offered on cruise liners that ply sea lanes originally developed for trade and migration, and appears in all parts of the tropics that used to be part of the Empire, unsuited to the climate though it may be. Back at home—where, as the writer Somerset Maugham famously observed, ‘To eat well in England you should have breakfast three times a day’—it is the one meal that is not confined to particular times, but is served all day in ordinary cafes up and down the land, as well as in chic London restaurants and hotels. Surveys of visitors to England regularly find that breakfast is the English meal that, above all others, tourists look forward to eating, while on holiday themselves, the English consistently order English or ‘cooked’ breakfasts as they are often called now, even if they don’t cook and eat them in their own homes. What is this apparent power over plate and palate exercised by the English Breakfast?

MAKING NATIONAL CUISINES

Far from being a footnote to history, anthropologists and historians have established that food is its very substance, the building blocks of nationhood and identity. Arjun Appadurai (1988) has shown how, in the early days of independence when Indian society was fragmented, the creation of a standard ‘Indian’ cuisine supported by a new genre of popular cookery books, was a major factor in achieving national unity. The development of a national cuisine played a similar role in the emergence of modern Italy (Helstosky 2003) and in the formation of local identity in the new Caribbean nation of Belize (Wilk 1999), while Ishige’s (2001) study of Japanese food shows the stages through which a much older national cuisine comes into being.

Food links body and spirit, self and society. It is both symbol and substance. National cuisines or dishes inspire strong passions, embody national values and are believed to be linked to the nation’s character, health and fortunes. As the philosopher and gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin put it—‘The destiny of nations depends on the manner in which they eat’. The anthropologist Mary Douglas (1975) has shown that to decipher a society’s meals and cuisine is to understand the society itself. As the English food writer P. Morton Shand (1929) observed, ‘The cookery of a nation is just as much part of its customs and traditions as are its laws and language’. It is through food, rather than political rhetoric, that people experience the nation in everyday life (C. Palmer 1998). To consume national dishes is not just an act of eating—it is the creation of the nation within the self.

The recipe for making national cuisines might read like this—take history, environment, culture, geography, politics, myth, chance and economics, and stir well together—but the mixture would never turn out the same way twice. Douglas (1997) captured the essence of food in just four words—‘food is not feed’. Cuisines are not just cookery techniques, recipes and ingredients—they are culture and history in edible form. All societies make different choices about food—how it is cooked, which foods are appropriate for which meals, when meals should be eaten, which foods are ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and much more. Different foods and ways of eating mark the boundaries between social classes, genders, ethnicities, religions and regions. Social, political, historical and economic changes are reflected in changes in foods and ways of eating—what Fischer (1989) called ‘foodways’. That is why different societies—or the same society in different periods of history—can begin with similar ingredients, and end up with entirely dissimilar cuisines.

* * *

The English writer George Orwell knew about food. He experienced the realities of haute cuisine by working in restaurant kitchens in Paris, where only a double door separated filthy sculleries and slaving minions from elegant customers dining in splendour. He wrote lyrically about English cooking, praising crusty English cottage loaves and Oxford marmalade, and in A Nice Cup of Tea he explained his eleven rules for obtaining a perfect brew at great length. He understood the politics of food and the pain of hunger, and food used as an instrument of power is a recurring theme in Animal Farm and 1984. Above all, Orwell was aware of the strength of tradition. As World War II raged and enemy bombers flew over London, he wrote in The Lion and the Unicorn (1940):

Yes, there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization. It is a culture as individual as that of Spain. It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own. Moreover it is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature. What can the England of 1940 have in common with the England of 1840? But then, what have you in common with the child of five whose photograph your mother keeps on the mantelpiece? Nothing, except that you happen to be the same person.

And above all, it is your civilization, it is you. However much you hate it or laugh at it, you will never be happy away from it for any length of time. The suet puddings and the red pillar-boxes have entered into your soul. Good or evil, it is yours, you belong to it, and this side the grave you will never get away from the marks that it has given you.

Few accounts are as illustrative of the power of tradition, and the subtle ways in which culture, cuisine and nation are linked. 1940, 1840, 1740, 1640, 1540, the centuries seem to merge and differences fall away in the face of an all-embracing English identity both ancient and resilient, reaffirmed at the start of every day through the eating of the national meal. But tradition is not always what it seems, because when Orwell was writing about solid English breakfasts with good bread and marmalade, the national meal of eternal England was actually less than a hundred years old.

This celebrated meal is also a culinary mystery. Early English cookbooks have recipes for lunch and for dinner, but no recipes at all for breakfast. Large breakfasts do not figure in English life or cookbooks until the nineteenth century, when they appear with dramatic suddenness. Why and how did breakfast come to be England’s national meal, and what is the ‘real’ English breakfast?

The development of cuisines, as Sir Jack Goody (1982, 1998) and others have shown, is a long and complex process. Over time, basic ingredients and cookery techniques begin to acquire particular associations, cultural meanings, socioeconomic significance and identity—a process that anthropologists call ‘the cultural biography of a thing’ (Kopytoff 1986). This identity is maintained over time, even though some of the ingredients, recipes and methods may change (Wilk 1999). National cuisines can be latent, existing on an implicit, taken-for-granted level until they are ‘rediscovered’, called into prominence by social conflict or crisis. As such, national cuisines are sensitive barometers of both change and fundamental values. Every national cuisine has a history, and every national meal has a biography that begins with the ingredients and becomes a cultural narrative over time.

Some food historians, notably Flandrin and Montanari (1999) have questioned the very concept of ‘national’ cuisines, arguing that long-established regional cuisines do not stop at shifting political borders. This regional approach may be appropriate in Europe where borders have always been fluid but it is less successful in the case of island nations like Japan and Great Britain where identity has been consolidated by geographical isolation. In any case it is seemingly impossible to separate nations from what they think of as their national cuisines, whether or not the cuisines are truly representative and even if they are entirely invented, as can be the case with new nations. The challenge is how to come to grips with the subject.

Many aspects of the process by which a national cuisine is formed can be seen in Naomichi Ishige’s The History and Culture of Japanese Food (2001). Ishige traces the development of Japanese cuisine from prehistory to the present, showing how various edible elements came to be present in Japan, how they took on cultural meaning, and how various dishes and ways of eating became inextricably linked with Japanese national identity. The same approach has been taken here to the biography of the English Breakfast.

* * *

The ingredients of the English Breakfast arrived in England long before the meal itself came into being. The variety and abundance of England’s produce has long been renowned, but archaeology has revealed that many of the foods and techniques now thought of as typically English, were imported from the continent in the course of successive waves of migration over thousands of years. The most notable contribution came from the Romans, who arrived in 43AD and, after a campaign against the Celtic inhabitants—described by the writer Diodorus Siculus as a fierce and savage people ‘looking like wood demons with hair like a horse’s mane’—established the island south of what is now Hadrian’s Wall as a province of the Roman empire, giving it the name Britannia.

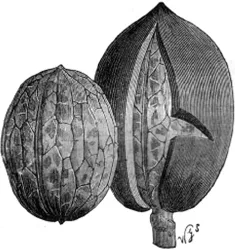

Over the three and a half centuries that they were in Britannia, the Romans are credited with introducing walnuts, cherries, types of beans and peas, rabbits, onions, leeks, carrots, parsley, radishes, spelt, fennel, mint, thyme, turnips, parsnips, pheasants, partridges, fallow deer, guinea fowl, mulberries, medlars, cucumbers, sweet chestnuts, a superior kind of domesticated chicken, cultivated apples, plums, pears and grapes. Cattle, sheep, pigs, and goats were already present, but the Romans introduced better breeds and husbandry practices. They brought vegetable gardens, orchards, cheese-making with rennet, bread baking in ovens, boiling fruit down to make jams and jellies, sausage-making and different ways of preserving hams and bacon.

This largesse was not accidental. Roman imperialism was political, economic, cultural—and culinary. They saw theirs as a civilizing mission and, once the fighting was over, they aimed to ‘Romanise’ their subject peoples by spreading the Latin language along with Roman values, customs, dress, architecture and cuisine. Praising Agricola’s fairness in dealing with the Celtic tribes, the Roman historian Tacitus observed ‘the result was that those who had just lately rejected the Raman tongue now conceived a desire for eloquence. Thus even our style of dress came into favour and the toga was everywhere to be seen. Gradually too they went astray into the allurements of evil ways, colonnades and warm baths and elegant banquets. The Britons, who had no experience of this, called it ‘civilization’ although it was part of their enslavement’. It has been said that after a conflict, the victors re-write history. They certainly re-write menus. Since antiquity, food has been used in this way as part of what the sociologist Norbert Elias (1994) later called ‘the civilizing process’.

From the Roman point of view, the Celts of Britannia and the Continent were richly deserving of culinary conquest. Julius Caesar claimed that the Britons were so barbaric they did not know how to sow crops. Strabo thought the people of Gaul little better than animals—‘To this day, they lie on the ground and take their meals seated on straw. They subsist principally on milk and all kinds of flesh, especially that of swine, which they eat both fresh and salted’—and was particularly appalled by the people of the Fenni tribe who, he reported, ‘live in an astonishingly barbaric and disgusting manner using wild plants for their food’, while Tacitus thought the German tribes primitive in the extreme—‘Their diet is simple: wild fruit, fresh game, curdled milk. They banish hunger without great preparation or appetising sauces.’ To the Romans, sauces were the very essence of civilised eating.

Roman descriptions of Celtic eating and provisioning practices were intentionally oversimplified, in order to show the benefits of Roman culinary influences in the best possible light. In fact, the pre-Roman Celts of Britannia and the Continent ate a late Iron Age diet that included wild and cultivated grains and seeds, the meat of sheep, cattle and pigs; game; wild fruits, roots and herbs, with fish and shellfish along the coasts and rivers. Small-scale agriculture was practiced. The staple dish was porridge or stew made from grains and seeds, to which meat, vegetables and herbs could be added according to season and circumstance. The most common method of cooking was boiling in a cauldron over an open fire. Spit-roasted meat was highly esteemed, but roasting consumed more fuel than boiling and also required young, tender cuts of meat. It was therefore an elite food and, along with beer or mead, was served at the feasts that were at the heart of Celtic culture. ‘No race’ wrote Tacitus, ‘indulges so lavishly in feast and hospitality. To close the door against a human being is a crime. Everyone, according to his property, receives at a well-spread board’.

Feasts were occasions when Celtic leaders could demonstrate their wealth and power, and strengthen their position by offering lavish hospitality to followers who would then be bound to them through the material and symbolic act of having taken their food. The importance of the feast is demonstrated by the presence in elit...