![]()

C

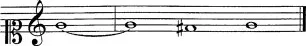

cadence (A) The association of ‘cadence’ with falling or a descent of notes in music at a pause or ending derives from Medieval and Renaissance practice. The cadence became a formal closure point either at various stages in the middle of a composition or at its end. Cadence therefore became synonymous with ‘close’ in music. Morley defined a cadence as: ‘A Cadence wee call that, when coming to a close, two notes are bound togither, and the following note descendeth thus:

or in any other keye after the same manner’ (Introduction, 1597, p. 73). In Renaissance music and earlier, a cadence was a melodic event and the main consideration was a linear descent to the ‘final’ of the predominant mode. In the late Renaissance, cadences became more concerned with bringing several voices or parts to a close and were determined by harmonic procedure. Campion, for example, was more progressive than Morley and stated that cadences or closes helped define key. In A New Way of Making Counterpoint (c.1614) he endeavoured to show how the progression of the bass (voice) determined this and articulated cadences. For the Elizabethans, there were three main or ‘formal’ closes depending on function and key. Dowland notes that ‘euery Song is graced with formall Closes, we will tell what a Close is. Wherfore a Close is (as Tinctor writes) a little part of a Song, in whose end is found either rest or perfection’ (Micrologus, 1609, p. 84).

The musical sense of falling and coming to an ending, either in the middle or conclusion, can be applied to poetry. Cadence is, of course, only applicable when the poetry is heard or spoken.

(B) There is only one occurrence of ‘cadence’ in the Shakespeare canon. In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Nathaniel is asked by the illiterate Jaquenetta to read the love letter that Armado has written to her. The letter contains a sonnet, and Holofernes criticizes Nathaniel’s way of delivering it:

You find not the apostraphas, and so miss

the accent. Let me supervise the canzonet.

Here are only numbers ratified, but for

the elegancy, facility, and golden cadence of poesy,

caret.

(4.2.119–23)

This rather complicated passage is meant to highlight Holofernes’ pedantic nature. He is worried that Nathaniel has not respected the metre of the poem. The reference to cadence ‘in the sense of rhythmical measure’ (David, p. 89) is the most obvious meaning of the word. But the speech has other musical terms in it – ‘accent’, ‘canzonet’ and later ‘fancy’ (125) – as does the sonnet quoted in the love letter: these seem to reveal Shakespeare’s willingness to evoke different layers of meaning in this passage.

See also harmony, melody, strain.

(C) David, Love’s Labour’s Lost (1951).

Herrisone, Music Theory in Seventeenth-Century England (2000).

Wilson (ed.), A New Way (2003), includes discussion of cadences.

canary (A) A lively duple-time dance of possible sixteenth-century Spanish origin. Whilst Arbeau (Orchesography, 1589) gives an example in ‘simple’ (¢) time, seventeenth-century versions appear more often in ‘compound’ rhythms (à la gigue), for example Cesare Negri, Le gratie d’amore (1602), and Praetorius, Terpischore (1612), no. 31. The dance begins on the first beat of the bar and is characterized by a dotted rhythm within a repeated two-bar phrase structure.

Arbeau relates the canary to the Spanish pavan. Whether the dance hails from the Canary Isles (the ‘Fortunate Isles’) is doubtful; but, as Arbeau suggests, its name connects it with the slightly wild and exotic: ‘sections are gay but nonetheless strange and fantastic with a strong barbaric character’ (Orchesography, p. 180). This makes its inclusion among English courtly dances (especially the revels of the courtly masques) doubtful but not impossible. It also has licentious and Bacchanalian overtones which Middleton observes: ‘Plain men dance the measures, the sinque pace the gay . . . You / Drunkards the canaries; you whore and bawd, the jig’ (Women Beware Women 3.3.218–19). Dekker seems to confirm this in The Wonderfull Yeare (1603): ‘A drunkard, who no sooner smelt the winde, but he thought the ground under him danced the canaries’ (F4v).

(B) Shakespeare mentions the canary three times out of a total of some fifty references to dances in his plays and poems. Another three references allude to ‘canary wine’, as in ‘O knight, thou lack’st a cup of canary. / When did I see thee so put down?’ (TN 1.3.80–1). A reference in The Merry Wives of Windsor involves a pun on both the dance and the alcoholic drink:

HOST: Farewell, my hearts. I will to my honest

knight Falstaff, and drink canary with him.

FORD [Aside]: I think I shall drink in pipe-wine

first with him; I’ll make him dance.

(3.2.87–90)

Word-play on ‘canary’, the dance or the drink, is found in Mistress Quickly’s explanation of Mistress Ford’s state of confusion and excitement. She tells the foolish Falstaff that he has managed to bring Mistress Ford ‘into such a canaries as / ’tis wonderful’ (2.2.60–1) and that not even the best courtier ever ‘brought her to such a canary’ (63). The bawdy context of the scene (which opens with a reference to Mistress Quickly’s loss of virginity) gives a sexual nuance to the lines.

Allusion to the lively, wild and bawdy nature of the dance is unmistakable when Lafew informs the King:

. . . I have seen a medicine

That’s able to breathe life into a stone,

Quicken a rock, and make you dance canary

With spritely fire and motion . . .

(AWW 2.1.72–5)

Lafew’s reference to ‘breathing life’ into inert things becomes more explicitly bawdy in the next few lines with the use of words such as ‘pen’ and ‘arise’. That same liveliness and innuendo are found when Moth advises Armado not to ‘brawl in French’, but ‘jig off a tune at the tongue’s end, canary to it with your feet’ (LLL 3.1.12–13).

(C) Brissenden, Shakespeare and the Dance (1981), p. 54.

Dolmetsch, Dances of Spain and Italy (1954).

Pulver, A Dictionary of Old English Music (1923), notes the dance (pp. 27ff.).

canton (A) A variant form of the Italian ‘canto’, meaning ‘a song’. It may also recall the French term, ‘chanson’, as well as being connected with the Italian ‘canzone’. Another form, ‘cantion’, appears in sixteenth-century English sources, e.g. Thomas (1587), meaning a [sweet] song, charm or enchantment.

(B) Shakespeare uses the word in Twelfth Night, when Viola, disguised as Cesario, woos Olivia by proxy and claims that, if she loved her as much as Orsino does, she would: ‘Write loyal cantons of contemned love, / And sing them loud even in the dead of night’ (1.5.270–1). In this context, ‘cantons’ is clearly synonymous with ‘songs’. Viola’s mention of unrequited (‘contemned’) love is dramatically ironic given that Olivia, thinking that Viola is a young gentleman, is falling in love with her.

(C) Thomas, Dictionarium Linguae Latinae et Anglicanae (1587).

canzonet (A) This word derives from the diminutive form of the Italian for ‘song’, generally of a popular style. It comes next after the madrigal in order of musical sophistication, according to Morley (Introduction, 1597, p. 180). Like the madrigal, each line of the poem set receives a contrapuntal treatment, or, as Morley puts it, ‘some point lightly touched’; and except for the middle section is repeated, thus A A’ B C C’. Like the English madrigal, the canzonet sets vernacular lyric poetry of a ‘light’ kind. It tends to be more syllabic in its treatment of the poem than the madrigal. Canzonets were both imported into England from Italy, where they were also known as ‘Canzoni alla Napoletana’, and also ‘Englished’, that is given English words to the Italian original, e.g. Morley Canzonets, Or Little Short Songs to Three Voyces (1593). Whilst the musical form of Morley’s canzonets is fairly consistent, the stanzaic form of the poems he sets is not. Stanzas vary between four and twenty lines.

(B) Holofernes requests that Nathaniel read ‘a staff, a stanza, a verse’ (LLL 4.2.103) of a canzonet. The musical nuance is established by ‘staff’, which could mean either ‘stanza’ or ‘musical stave’. Although musical imagery, relating to celestial and mundane musics, is present in the last four lines of the canzonet:

Thy eye Jove’s lightning bears, thy voice his dreadful thunder,

Which, not to anger bent, is music and sweet fire.

Celest...