- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collected Works, Volume 2

About this book

Among the most influential political and social forces of the twentieth century, modern communism rests firmly on philosophical, political, and economic underpinnings developed by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, later known as Lenin. For anyone who seeks to understand capitalism, the Russian Revolution, and the role of communism in the tumultuous political and social movements that have shaped the modern world, the works of Lenin offer unparalleled insight and understanding.

This second volume contains Lenin's works from 1895 to 1897. Included are Lenin's early economic and political writings, as well as his prescriptions for the program and strategy of Russian Marxism.

This second volume contains Lenin's works from 1895 to 1897. Included are Lenin's early economic and political writings, as well as his prescriptions for the program and strategy of Russian Marxism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

A CHARACTERISATION

OF ECONOMIC ROMANTICISM

(SISMONDI AND OUR NATIVE SISMONDISTS)44

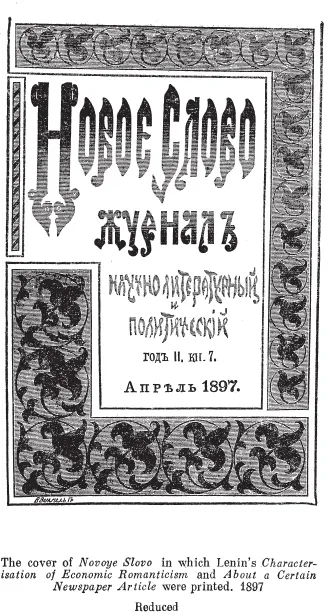

Written in the spring 1897 First published in the magazine Novoye Slovo,45 issues 7-10, April-July 1897. Signed: K. T—n Reprinted in the miscellany Economic Studies and Essays by Vladimir Ilyin, 1898 | Published according to the text of the miscellany Economic Studies and Essays, checked with the text in Novoye Slovo and that in the miscellany The Agrarian Question by Vl. Ilyin, 1908 |

The Swiss economist Sismondi (J.-C.-L. Simonde de Sismondi), who wrote at the beginning of the present century, is of particular interest in considering a solution of the general economic problems which are now coming to the forefront with particular force in Russia. If we add to this that Sismondi occupies a special place in the history of political economy, in that he stands apart from the main trends, being an ardent advocate of small-scale production and an opponent of the supporters and ideologists of large-scale enterprise (just like the present-day Russian Narodniks), the reader will understand our desire to outline the main features of Sismondi’s doctrine and its relation to other trends—both contemporary and subsequent—in economic science. A study of Sismondi is today all the more interesting because last year (1896) an article in Russkoye Bogatstvo also expounded his doctrine (B. Ephrucy: “The Social and Economic Views of Simonde de Sismondi,” Russkoye Bogatstvo, 1896, Nos. 7 and 8).*

The contributor to Russkoye Bogatstvo states at the very outset that no writer has been “so wrongly appraised” as Sismondi, who, he alleges, has been “unjustly” represented, now as a reactionary, then as a utopian. The very opposite is true. Precisely this appraisal of Sismondi is quite correct. The article in Russkoye Bogatstvo, while it gives an accurate and detailed account of Sismondi’s views, provides a completely incorrect picture of his theory,* idealises the very points of it in which he comes closest to the Narodniks, and ignores and misrepresents his attitude to subsequent trends in economic science. Hence, our exposition and analysis of Sismondi’s doctrine will at the same time be a criticism of Ephrucy’s article.

CHAPTER I

THE ECONOMIC THEORIES OF ROMANTICISM

The distinguishing feature of Sismondi’s theory is his doctrine of revenue, of the relation of revenue to production and to the population. The title of Sismondi’s chief work is: Nouveaux principes d’économie politique ou de la richesse dans ses rapports avec la population (Seconde édition. Paris, 1827, 2 vol. The first edition was published in 1819)—New Principles of Political Economy, or Wealth in Relation to Population. This subject is almost identical with the problem known in Russian Narodnik literature as the “problem of the home market for capitalism.” Sismondi asserted that as a result of the development of large-scale enterprise and wage-labour in industry and agriculture, production inevitably outruns consumption and is faced with the insoluble task of finding consumers; that it cannot find consumers within the country because it converts the bulk of the population into day labourers, plain workers, and creates unemployment, while the search for a foreign market becomes increasingly difficult owing to the entry of new capitalist countries into the world arena. The reader will see that these are the very same problems that occupy the minds of the Narodnik economists headed by Messrs. V. V. and N. —on.46 Let us, then, take a closer look at the various points of Sismondi’s argument and at its scientific significance.

I

DOES THE HOME MARKET SHRINK

BECAUSE OF THE RUINATION OF THE SMALL PRODUCERS?

Unlike the classical economists, who in their arguments had in mind the already established capitalist system and took the existence of the working class as a matter of course and self-evident, Sismondi particularly emphasises the ruination of the small producer—the process which led to the formation of the working class. That Sismondi deserves credit for pointing to this contradiction in the capitalist system is beyond dispute; but the point is that as an economist he failed to understand this phenomenon and covered up his inability to make a consistent analysis of it with “pious wishes.” In Sismondi’s opinion, the ruination of the small producer proves that the home market shrinks.

“If the manufacturer sells at a cheaper price,” says Sismondi in the chapter on “How Does the Seller Enlarge His Market?” (ch. III, livre IV, t. 1, p. 342 et suiv.),* “he will sell more, because the others will sell less. Hence, the manufacturer always strives to save something on labour, or on raw materials, so as to be able to sell at a lower price than his fellow manufacturers. As the materials themselves are products of past labour, his saving, in the long run, always amounts to the expenditure of a smaller quantity of labour in the production of the same product.” “True, the individual manufacturer tries to expand production and not to reduce the number of his workers. Let us assume that he succeeds, that he wins customers away from his competitors by reducing the price of his commodity. What will be the ‘national result’ of this?… The other manufacturers will introduce the same methods of production as he employs. Then some of them will, of course, have to discharge some of their workers to the extent that the new machine increases the productive power of labour. If consumption remains at the same level, and if the same amount of labour is performed by one-tenth of the former number of hands, then the income of this section of the working class will be curtailed by nine-tenths, and all forms of its consumption will be reduced to the same extent…. The result of the invention—if the nation has no foreign trade, and if consumption remains at the same level—will consequently be a loss for all, a decline in the national revenue, which will lead to a decline in general consumption in the following year” (I, 344). “Nor can it be otherwise: labour itself is an important part of the revenue” (Sismondi has wages in mind), “and therefore the demand for labour cannot be reduced without making the nation poorer. Hence, the expected gain from the invention of new methods of production is nearly always obtained from foreign trade” (I, 345).

The reader will see that in these words he already has before him all that so-familiar “theory” of “the shrinkage of the home market” as a consequence of the development of capitalism, and of the consequent need for a foreign market. Sismondi very frequently reverts to this idea, linking it with his theory of crises and his population “theory”; it is as much the key point of his doctrine as it is of the doctrine of the Russian Narodniks.

Sismondi did not, of course, forget that under the new relationships, ruination and unemployment are accompanied by an increase in “commercial wealth” that the point at issue was the development of large-scale production, of capitalism. This he understood perfectly well and, in fact, asserted that it was the growth of capitalism that caused the home market to shrink: “Just as it is not a matter of indifference from the standpoint of the citizens’ welfare whether the sufficiency and consumption of all tend to be equal, or whether a small minority has a superabundance of all things, while the masses are reduced to bare necessities, so these two forms of the distribution of revenue are not a matter of indifference from the viewpoint of the development of commercial wealth (richesse commerciale).* Equality in consumption must always lead to the expansion of the producers’ market, and inequality, to the shrinking of the market” (de le [le marché] resserrer toujours davantage) (I, 357).

Thus, Sismondi asserts that the home market shrinks owing to the inequality of distribution inherent in capitalism, that the market must be created by equal distribution. But how can this take place when there is commercial wealth, to which Sismondi imperceptibly passed (and he could not do otherwise, for if he had done he could not have argued about the market)? This is something he does not investigate. How does he prove that it is possible to preserve equality among the producers if commercial wealth exists, i.e., competition between the individual producers? He does not prove it at all. He simply decrees that that is what must occur. Instead of further analysing the contradiction he rightly pointed to, he begins to talk about the undesirability of contradictions in general. “It is possible that when small-scale agriculture is superseded by large-scale and more capital is invested in the land a larger amount of wealth is distributed among the entire mass of agriculturists than previously” … (i.e., “it is possible” that the home market, the dimension of which is determined after all by the absolute quantity of commercial wealth, has expanded—expanded along with the development of capitalism?)…. “But for the nation, the consumption of one family of rich farmers plus that of fifty families of poor day labourers is not equal to the consumption of fifty families of peasants, not one of which is rich but, on the other hand, not one of which lacks (a moderate) a decent degree of prosperity” (une honnête aisance) (I, 358). In other words: perhaps the development of capitalist farming does create a home market for capitalism. Sismondi was a far too knowledgeable and conscientious economist to deny this fact; but—but here the author drops his investigation, and for the “nation” of commercial wealth directly substitutes a “nation” of peasants. Evading the unpleasant fact that refutes his petty-bourgeois point of view, he even forgets what he himself had said a little earlier, namely, that the “peasants” became “farmers” thanks to the development of commercial wealth, “The first farmers,” he said, “were simple labourers…. They did not cease to be peasants…. They hardly ever employed day labourers to work with them, they employed only servants (des domestiques), always chosen from among their equals, whom they treated as equals, ate with them at the same table … constituted one class of peasants” (I, 221). So then, it all amounts to this, that these patriarchal muzhiks, with their patriarchal servants, are much more to the author’s liking, and he simply turns his back on the changes which the growth of “commercial wealth” brought about in these patriarchal relationships.

But Sismondi does not in the least intend to admit this. He continues to think that he is investigating the laws of commercial wealth and, forgetting the reservations he has made, bluntly asserts:

“Thus, as a result of wealth being concentrated in the hands of a small number of proprietors, the home market shrinks increasingly (!), and industry is increasingly compelled to look for foreign markets, where great revolutions (des grandes révolutions) await it” (1, 361). “Thus, the home market cannot expand except through national prosperity” (I, 362). Sismondi has in mind the prosperity of the people, for he had only just admitted the possibility of “national” prosperity under capitalist farming.

As the reader sees, our Narodnik economists say the same thing word for word.

Sismondi reverts to this question again at the end of his work, in Book VII On the Population, chapter VII; “On the Population Which Has Become Superfluous Owing to the Invention of Machines.”

“The introduction of large-scale farming in the countryside has in Great Britain led to the disappearance of the class of peasant farmers (fermiers paysans), who worked themselves and nevertheless enjoyed a moderate prosperity; the population declined considerably, but its consumption declined more than its numbers. The day labourers who do all the field work, receiving only bare necessities, do not by any means give the same encouragement to urban industry as the rich peasants gave previously” (II, 327). “Similar changes also took place among the urban population…. The small tradesmen, the small manufacturers disappear, and one big entrepreneur replaces hundreds of them who, taken all together, were perhaps not as rich as he. Nevertheless, taken together they were bigger consumers than he. The luxury he indulges in encourages industry far less than the mode...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1895

- 1896

- 1897

- Notes

- The Life and Work of V. I. Lenin. Outstanding Dates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Collected Works, Volume 2 by V. I. Lenin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.