eBook - ePub

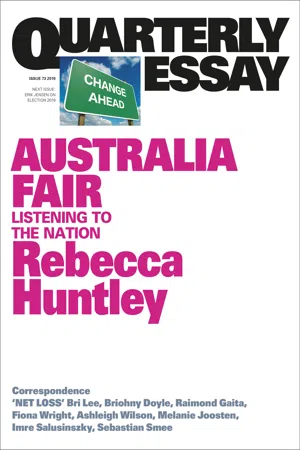

Quarterly Essay 73 Rebecca Huntley on Australia's New Progressive Centre

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Quarterly Essay 73 Rebecca Huntley on Australia's New Progressive Centre

About this book

For some time, a majority of Australians have been saying they want change – on climate and energy, on housing and inequality, on corporate donations and their corrupting effect on democracy, to name just a few.

Recent attention has focused on the angry, reactionary minority. But is there a progressive centre? How does it see Australia's future? And what is to be learned from the failures of previous governments? Was marriage reform just the beginning, or will the shock-jocks and their paymasters hold their ground?

In this vivid, grounded essay, Rebecca Huntley looks at the state of the nation and asks: what does social-democratic Australia want, and why?

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

AUSTRALIA FAIR | Listening to the nation |

Rebecca Huntley |

It was the week before Christmas and Adelaide was alive with Labor Party people, as well as journalists, unionists, protesters, fellow travellers, interested observers and the men and women of business and civil society, there to network assertively with what was likely to be the next federal government. It was the Australian Labor Party National Conference, held every three years, at which Labor updates its platform and policies, showcases its leaders and tries to speak to both base and electorate. This 2018 conference had to radiate unity and readiness to take power. And it seemed to do just that.

It was my first conference in about fifteen years. I was intrigued to see who stalked the corridors of the Adelaide Convention Centre. Kon Karapanagiotidis from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre was there, hoping that the party would endorse more compassionate policies on asylum seekers. Tim Winton floated in and out, attracting admiring stares from political animals who read fiction, hoping to get a commitment from Labor to protect his beloved Ningaloo Reef. These two issues – asylum seekers and the environment – have derailed Labor many times in the past twenty years, assisting in the bleeding of votes to the Greens in inner-city Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, and worrying the hardheads of the Right focused on marginal seats in Queensland and western Sydney.

In 2018, Labor politicians and delegates talked about how a Shorten Labor government would make Australia a fairer, more compassionate, greener and smarter place. I thought to myself that this was, in fact, not quite true. The majority of Australians already inhabit such a place, at least in their beliefs and outlook. In that respect, they have been ahead of the political class for many years now. The role of a new federal Labor government would not be to change hearts and minds. All a Labor government would have to do – if it were to fulfil its election commitments – is update policy and law to reflect the views and desires of the democratic majority.

In the week before the conference, my father asked me about the Labor leader. What would a Prime Minister Shorten be like?

I paused to reflect, then said, “You know, it’s going to be fine.”

My sister retorted, “Well, there’s a decline for you. The Labor Party has gone from ‘It’s time’ to ‘It’s fine’ in three generations.”

It’s not surprising that voters like my sister have scaled back their hopes for a visionary government, after the disappointments of Kevin 07. For a moment then, it seemed a modern Labor government under Kevin Rudd would fuse the traditional politics of social and economic justice for working- and middle-class people with a new politics of belief in action on climate change. And remain in government for numerous terms to cement its vision for the future.

The only grand visions Australians see nowadays are beamed to us across the Pacific, the erratic ideas of an extreme-right populism, which mostly provoke fear and loathing here. And yet the conditions exist for Labor to be something more than just an “It’s fine” government, for it to do more than merely catch up with the people. There is an opportunity to renew social democracy, Australian-style. The main aim of social democracy – to “reconcile capitalism, democracy and social cohesion” – is even more relevant after the global financial crisis, the banking royal commission and with rising economic inequality.

A revived democracy is possible – if Labor is willing not only to follow through on its policy pledges, but also to enact and embed a new social-democratic tradition with environmental concerns at its core. If it has the guts to respond to public anger about corruption and corporate influence on the political class. If it has the determination and skill to use a different political rhetoric to frame the issues that matter to Australians – not just by what is merely profitable, but by what is right. And if it can muster the gumption to argue creatively and consistently that the social-democratic policies that many of us want require not only reform of the taxation system to make it more equitable, but also higher taxation across the board. That is what a truly progressive politics would look like. In many respects, it would be the expression of the wishes of the majority of Australians, who are desperate not just to “move forward,” but to see genuine progress, in our country and our politics.

The views of this democratic majority – on issues such as housing, the environment, immigration and aspects of our democratic system – may or may not surprise the reader. But understood in their complexity, these views show clearly that the opportunity is there for an incoming Labor team to be bold in its approach to government, unapologetic in its advocacy for the public sector, and courageous in its leadership on the environment. Even on the vexed issue of immigration and asylum seekers, there is potential for a less defensive, more open approach. All in all, Australians are ready for reform, and more ready for the revival of social democracy than many assume.

THE UN-SILENT MAJORITY

How do we know this about the Australian people? Because the research tells us so. I am a social and market researcher, involved in the “dark arts” of focus groups, polling, surveys, and strangers who ring you in the middle of dinner to ask your view of your local candidate. No doubt my profession has been under attack for many years as contributing to the corruption and mendacity of party politics. Not only are our methods questioned, and the ways in which our work is used criticised, but the veracity of our conclusions is constantly doubted. It’s common for commentators to say on election night that the polls got it wrong. Even our nearest and dearest can join in the chorus of disapproval: as a jokey response whenever a work colleague asks what his wife does for a living, my husband replies, “She’s an expert in the opinions of people who don’t know what they are talking about.”

While it is true that some polling (namely, seat-based robo-polling) can be unreliable, there is no evidence that national political polls in Australia are inaccurate. In fact, history shows that such polls produce exceptionally accurate results, even with the transition from landlines to mobile phones and online surveys over the past decade or so. As well as many national polls, there are myriad datasets on politics, including the Australian Election Study (AES), the Australian Values Survey (AVS), the Scanlon Foundation’s various reports, and issues polls such as the Essential Report, the Ipsos Issues Monitor and the Lowy Institute Poll. Increasingly, the CSIRO and like organisations are also doing substantial research on public attitudes. Taken together, this research gives a consistent and reliable picture of where the majority of Australians sit, not just on politics but on a range of issues. Thanks to compulsory voting, there is no silent majority in Australia. There is an un-silent majority, whose views are plain to discern.

But are these views being heeded by our political leaders? Often the claim is made that our politics and politicians are poll-driven. This is, on the whole, bunkum. While fluctuations in the polls might be used by political frenemies to destabilise, there is no consistent evidence that the policy agenda of the major parties has been shaped mainly by opinion polls. If such polls were influential on policy and politics, we would have made big investments in affordable and social housing, banned foreign donations to political parties and further curtailed corporate donations to political parties, invested much more in renewable energy, maintained and even increased funding to the ABC, and made child care cheaper. We would have also made marriage equality a reality through an act of parliament, without an expensive and hurtful postal survey (the most wasteful piece of market research in the history of Australia). We may already have made changes to negative gearing and moved towards adopting elements of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. We would have made euthanasia legal across the country and started the process leading to a republic. We would have put more funding into Medicare and the National Disability Insurance Scheme. We would have taken up the first iteration of the Gonski education reforms. We would be installing a world-class national broadband network. These are some of the issues on which this democratic majority comes together: topics that attract 60 per cent or higher public support if we refer to all the available surveys, a basic agreement crossing party lines, stretching from soft Liberal and Labor to Green and independent voters – and even (on some issues such as euthanasia and donation reform) to One Nation voters.

While we are on the topic of polling and trust, we should also confront the other fallacy doing the rounds: that Australians have lost faith in politics, government, even democracy itself. That trust in institutions is at an all-time low. The statement that there is a widespread decline of trust in institutions of all kinds is repeated so often that it has become a truism. It’s presented without any real context or conclusions about what this might mean for our politics. Even a casual reader of our colonial history would know Australians have never really trusted politicians. So, the low trust in political parties is not surprising, and any downward trend there is unlikely to be reversed easily. Assisted by numerous royal commissions and scandals, there has also been a decline of trust in religious organisations, business groups and even charities.

According to the Essential Report in 2018, the top trusted institutions are the federal and state police (70 per cent and 67 per cent), the High Court (61 per cent), the ABC (54 per cent) and the Reserve Bank (50 per cent). Despite our cynicism, Australians still have some faith in the institutions that uphold the rule of law, direct the economy, and check and balance the powerful. Political parties are at the bottom of the trust list, according to Essential, at 15 per cent. The AVS, coming out of the Australian National University, confirms that very few Australians express confidence in the country’s political parties, and that number is declining even further. In 2018, 27 per cent of Australians reported having “no confidence at all” in political parties. No more than 1 per cent of Australians expressed “a great deal” of confidence in parties on any of the four occasions the question has been asked since 1981. Furthermore, the AES shows that the proportion of Australians who agree that “people in government can be trusted” (by which they mean politicians and the public service) has declined from 51 per cent in 1969 to 26 per cent in 2016. These numbers reflect conversations I’ve heard in focus group after focus group over the last decade and a half. Australians see corruption everywhere and believe that almost everyone has a self-serving agenda. They are always on the lookout for the lie, the rip-off, the hustle, whether it be from a telemarketer, tradie, minister of government or minister of religion.

However, has this lack of trust in politicians and parties strangled engagement in our democratic life? I judge that it has not – yet. While Australians are disdainful of party politics, most of us are still interested in political issues. In October 2018, a few months after the Liberal Party leadership spill, an Ipsos survey found that 59 per cent of Australians described themselves as “very” or “fairly” interested in politics. The AES shows that around 43 per cent of Australians say they have some interest in politics and 34 per cent a good deal; these levels of interest have remained stable over three decades. The participants in the focus groups I conduct might not be across the detail of politics – the name of the Minister for Trade, or who said what in Question Time – but they have lots to say about the big issues that face this country. They are interested in policy but not necessarily capital P politics or the small-minded, petty squabbles they see played out in the media.

If we look at just the bare facts of voting – enrolment, participation and informality – then our faith in democracy seems fairly robust. Informality (making a deliberate or accidental error in voting which means your vote can’t be counted in the ballot) has actually decreased in recent years. Enrolment is at 96.2 per cent of the eligible population. Since the introduction of compulsory voting in 1924, turnout at elections jumped to over 90 per cent and has remained largely stable. While there has been a slight downward trend in turnout from the 1990s, it is “so slight that it barely warrants the term ‘decline’.” While turnout is dependent on age, with young people less likely to vote, the AEC has found no generational effect in non-voting in Australia.

In other words, voting is something all Australians grow into, regardless of what generation they belong to. The announcement of the same-sex marriage survey in 2017 saw 90,000 new voters, most of them young, enrol in time to respond, defying those who characterise young people as apathetic, and annoying the “No” campaigners who hoped to profit from their apathy. (This doesn’t mean all is well with young Australians and the current state of democracy and politics, but more on that later.) Indeed, the same-sex marriage survey is one of the best examples of Australians’ active involvement in democracy. The response to a survey that was mailed to people (old-school) and not compulsory (practically un-Australian) was extraordinary: 79.5 per cent of those who received a survey submitted a response.

Some might dismiss this high level of voter engagement as a Pavlovian response to the threat of a fine and the promise of a sausage sizzle. But, as political scientists Sarah Cameron and Ian McAllister point out, “A majority of voters consistently support compulsory voting, and there has been relatively little change in these proportions since the 1950s.” In fact, while support for compulsory voting has remained in the 70s for decades, a still higher percentage of Australians indicate they would vote even if it wasn’t compulsory – in 2016, that figure was 80 per cent. Among all the perceived evils and ills of domestic politics Australians have pointed out to me, compulsory voting has rarely been one of them.

While compulsory voting in itself doesn’t guarantee a meaningful democracy, it has the effect of creating a broad sense that voting is an important obligation (rather than a freedom to exercise or not), like obeying the road rules. It also creates a political culture that, on the whole, has to speak to the reasonable majority. Despite the focus in election campaigns on swinging voters and marginal seats, the two major political parties have to pitch to the centre. They don’t have to “turn out their base,” as parties need to do in the United States and the United Kingdom. Extreme policies and slogans that beat the partisan drum aren’t necessarily required in a high-turnout environment. Historian John Hirst may be right when he describes compulsory voting as “the most distinctive characteristic of the Australian system.” In some respects, compulsory voting is the glue that keeps the democratic majority – which is on the whole centrist and sensible – together.

And what about belief in democracy itself? How has that weathered the leadership changes of the past decade? Has the fact that the party machines kneecapped the last four elected prime ministers undermined our belief that democracy can deliver stable government? Again, much of the research seems to say no. The most recent wave of data from the AVS found that we are committed to the concept of democracy and largely believe Australia is being governed in a democratic manner.

Almost nine in ten Australians believe that “having a democratic political system” is either a “very good” or “fairly good” form of government. Further, that percentage has been increasing since 1995. Importantly, more than half of all Australians believe it is “absolutely important” to live in a country that is governed democratically. This suggests that, for most Australians, democracy is still the “only game in town.”

But are we playing that game well? Trends over time charted in the AES suggest escalating doubts. The care factor about who wins the federal election has bounced around over the years, reaching high points in 1987, 1993 and 2007 only to settle at around 65 per cent in 2016. The proportion reporting “a good deal of interest” in the election itself has steadily declined from 50 per cent in 1993 to 30 per cent in 2016. Similarly, satisfaction with democracy reached a high point in 2007 of 86 per cent – Kevin 07! – only to plummet to 60 per cent in 2016. Research commissioned by the Museum of Australian Democracy suggests that while we support the concept of democracy, we aren’t happy with how it works in practice, with fewer than 41 per cent of citizens currently satisfied, down from 86 per cent in 2007.

Another worrying result – reflected in the AES – concerns the perceived effect of casting a vote. In 1997, 70 per cent agreed that “who people vote for can make a big difference.” In 2016, that figure was 58 per cent. The decline could be a consequence of many things, including cynicism that big changes won’t be made by either Labor or Liberal when in government, or increasing awareness that a vote in a marginal seat matters more than one in a safe seat. Or the sense that the messages voters send through the ballot box (invest in infrastructure! more funding for health and education!) aren’t being heard by those elected. Indeed, the most interesting insight may be into Australians’ perception of how politicians feel about them. In 2016, only 22 per cent agreed with the statement: “Parties care what people think.” This figure has fluctuated only a little over the years. Despite the large increase in surveys and polls of all kinds and increasing politician/constituent communication, just over half of the respondents to the 2016 AES agreed with the statement that politicians know what ordinary people think. It seems that while voters are constantly being asked their opinion, they are not convinced they are being listened to.

So trust in political parties is low and trust in other institutions is generally declining. Voter frustration is high. And yet there hasn’t been an equivalent loss of faith in democracy – in theory, if not in practice. It is extraordinary that despite peak cynicism when it comes to politicians, we still support the processes that see them elected to run our governments.

Accompanying this faith in democracy is a belief in the vital role of government. I would argue that the public believes in this role more strongly now than at any time since the 1980s. Understanding that enduring belief is critical to understanding social democracy, Australian-style, and how it might be revitalised.

THE AUSTRALIAN SETTLEMENT

Australians find it hard to define what it is to be Australian. They are probably better at identifying what is un-Australian. For some, the WorkChoices policy John Howard took to the 2007 election was un-Australian. Refugees who “jump the queue” are un-Australian. Giving jobs to migrant workers or sending jobs overseas is un-Australian. Big apartment blocks are un-Australian. Getting rid of penalty rates is un-Australian. And banning Christmas carols at primary schools is un-Australian. We generally still place the ideal of fairness or a fair go at the heart of what this nation is about. People struggle even more when it comes to describing the best kind of government for our country, the kind that will guarantee that fair ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Australia Fair

- Correspondence

- Contributors

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Quarterly Essay 73 Rebecca Huntley on Australia's New Progressive Centre by Rebecca Huntley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.