![]()

Part 1

The International Feminist Collective: Historical Overview and Political Perspective

![]()

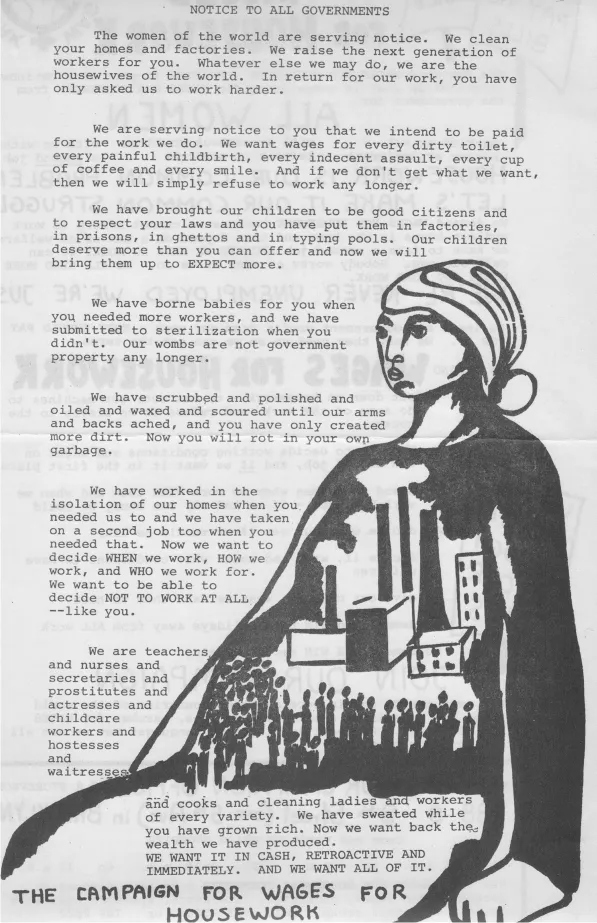

Figure 1.1 “Notice to All Governments.” Tract distributed during many demonstrations organized by Wages for Housework. Drawing: Jacquie Ursula Caldwell. Text: Judy Quinlan, Toronto Wages for Housework Committee.

1

1972: Wages for Housework in the Universe of Feminism

How can we give a fair accounting, so many years later, of this current of feminist thought and the movement that underpinned it? How can we explain the thought and actions of this movement meaningfully and comprehensibly, when the political and cultural context and the intellectual climate during which it took place were so utterly different from today’s? How can it resonate in the present? How can we extrapolate from it to offer, as I propose in this book, relevant tools for addressing the gendered division of labour and for critiquing dominant systems and the different social relations that they bring about?

We simply have to remember how removed and old-fashioned Simone de Beauvoir’s essay Le deuxième sexe, published in 1949 (translated as The Second Sex), and especially its second volume, L’expérience vécue (translated as Lived Experience), seemed from our realities at the turn of the 1970s. Born in the postwar years, we were eagerly seeking theoretical bases for our new feminism. Le deuxième sexe had been published twenty years before, which seemed to put it in an impossibly distant past. And yet, the current of thought and the movement that I discuss here took place not twenty years but double that, forty years, ago. To young people today, that probably seems like the Middle Ages.

Therefore, it is necessary to provide a context – the social, intellectual, and activist horizons of feminism, and the daily life of women, forty years ago – in order to understand the world in which a book such as The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community appeared in 1972. This context also clarifies the contributions that the book made to the neo-feminist landscape of ideas and action that was surging onto the political scene at the time.1

A GLANCE AT THE DAILY LIFE OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY 1970S

In most Western countries where what is commonly called neo-feminism or second-wave feminism appeared, the legal equality of women was far from a settled matter. In Quebec, for example, women could not serve on juries, and civil marriage and divorce had just been legalized, as had homosexuality “between consenting adults.”2 Access to abortions was in the process of being liberalized: at first very restricted, it also depended on the goodwill of physicians.3 Advertising of contraceptive methods was illegal. Access to the Pill was chancy, as one had to find a physician who was willing to prescribe it.

Pay equity was an illusion: in general, women earned half what men did. If they complained, they were likely to be fired. Rape was a criminal offence, unless it was rape of a wife. However, unlike for every other criminal offence, the rape victim was presumed guilty and had to prove her innocence in court. Similarly, any woman suspected of “prostitution” had to explain her presence in a public place whenever asked by the police. In 1970s, the Canadian Criminal Code still treated prostitution as a “crime of status”: it penalized women for who they were and not for what they did.4 Meanwhile, Indigenous women living on reserves were in an aggravated discriminatory situation: they lost their status and their rights if they married a non-Indigenous man.5

In the early 1970s, financially accessible daycare centres were non-existent for all intents and purposes. The female labour force participation rate formed between one-quarter and one-third of the total female population, depending on the country (rising toward 40 percent in some European countries and North America).6 This meant that the proportion of women whose occupation was full-time housekeeper was around two-thirds, ranging from 60 percent in Quebec to 72 percent in Italy. Half of the wives of immigrants to Canada worked outside the home.7

The unionization rate of women wage earners was very low, and they worked mainly in female “job ghettos” (in jobs related to their tasks in the home). In practice, the career of women wage earners followed this path: when the first child came, they left the job market; they rejoined it when the children were grown. In both situations, women’s workday was assessed as follows: “The housewife in the labour force and the housewife with two or more children are likely to work over 11 hours a day. An 11-hour work day on a regular basis would not be countenanced in industry.”8

Meanwhile, the situation of married women in the home left much to be desired in 1970. Again using the example of Quebec, the province was heir to the Napoleonic Code and French civil law, which considered women to be “incapable,” like minors and the “feebleminded.” Marital and paternal power prevailed in all circumstances, and women and children were subjected to it. In 1964, the Act Respecting the Legal Capacity of Married Women (tabled by the first woman elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, Claire Kirkland-Casgrain) partially remedied the situation, although the statute was far from being fully integrated into society at the end of the 1960s.

Governments were little inclined to change things before the arrival of neo-feminism. In Canada, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, created in the late 1960s under pressure from women’s groups and mandated to recommend to the federal government measures to put women on the path to equality, said little about the situation of women in the home. Aside from one major recommendation that “housewives should be entitled to pensions in their own right under the Canada Pension Plan or the Quebec Pension Plan” and a few minor recommendations, the commission threw up its hands: “With few rare exceptions, the woman who stays at home depends on her husband for money ... Unfortunately, we have no over-all solution for the financial dependency of housewives.”9

It was not until the resurgence of neo-feminism, in 1971–72, that the first large-scale study on the situation of houseworkers was published by a collective of feminist activists, some of whom came from the defunct Front de libération des femmes du Québec (1969–71).10 This first attempt at a general compilation of data on the situation of women working full time in the home was used, in the years that followed, as a training and intervention tool by numerous activists in the feminist, community, and union movements, and also by political parties.

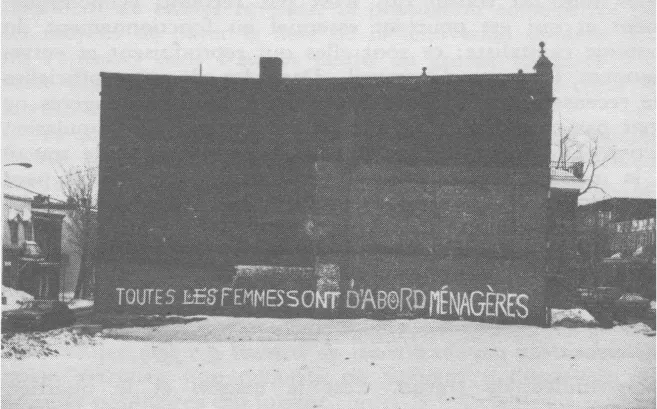

When Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James came to Montreal in the spring of 1973 to discuss the ideas expressed in their book, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, many women recognized themselves in the discourse expressed by the authors, according to which “all women are houseworkers.” The question was already in the air. Opposition political parties on both the left and the right were weighing the idea of paying “the housewife” (and not the housework itself, regardless of the person performing it). The National Council of Welfare, an independent agency charged with advising the Canadian government on welfare, recommended such wages in its 1972 report.11 Similarly, in 1973, some authors, such as Marcelle Dolment and Marcel Barthe, suggested the creation of a “new class of workers” called “home educators.”12 They proposed that this aspect of housework be paid: a full-time wage for parents of children aged zero to six years, and a half-time wage for parents of children six to thirteen years; the parent who decided to stay at home for this period of the children’s life would receive the salary. Among women’s associations, AFEAS (Association féminine d’éducation et d’action sociale), the membership of which was mainly women at home, had been demanding an “allowance for the mother at home in recognition of the work of educating small children” since 1968.13

The perspective expressed by Dalla Costa and James in The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community was different. Like so many other neo-feminist demands, it was anchored in a critique of society. “The neo-feminists’ new contribution, however, was to include these demands in an analysis of society that completely challenged the traditional role of women within the family and aimed to fight against the profound causes of the specific oppression of which women were victims” ... in capitalist society, I would add, to be faithful to the spirit of the times.14 Neo-feminism, in effect, was born in the wake of the New Left.

Figure 1.2 Graffiti: “Toutes les femmes sont d’abord ménagères” (All women are houseworkers first). Photo: Raymonde Lamothe.

NEO-FEMINISM: IN THE CIRCLE OF INFLUENCE OF THE NEW LEFT

A shared social and intellectual climate brought autonomous groups of women together as neo-feminism was being born.15 This early era was that of the publication of The Power of Women. Some neo-feminist authors sought to identify the currents of feminist ideas emerging at the time. In general, there were three major trends, united under the banner of the autonomous struggle of women: a reformist (or liberal) trend, a “New Left” trend (bringing together “revolutionary feminists” or “politicos” or unorthodox socialists and Marxists), and a cultural or “women’s lib” trend, which would be called radical and also included leftist feminists.16 For the purpose of this book, I limit myself to the intellectual sphere of the last two trends, as they are more pertinent to my subject. Because at first they were not clearly delineated, these trends require a few clarifications.

The New Left

The New Left, a banner under which many activists were gathered at the inception of neo-feminism, was essentially an eclectic movement in terms of ideology, and very differentiated by country and by tradition of thought on social transformation. In the United States, New Left feminist activists drew on the ideals borne by the anti-racist struggles of the civil rights movement and were much less marked and influenced by the tradition of socialist and Marxist thought than were the activists in France, Italy, and Great Britain. In Quebec, a “colonial-colonized” society, a go...