![]()

CHAPTER ONE

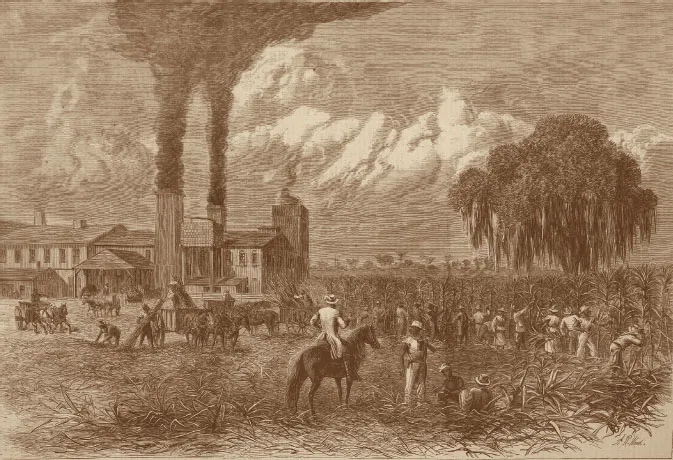

The very origin of the landscape of Terrebonne Parish in south central Louisiana gave rise to the lucrative sugar industry that peaked locally in the nineteenth century and still endures in lesser eminence today. Sugar cane production in the region dates back to before the time the Louisiana legislature established Terrebonne as a parish (county) in 1822.

Built as delta land of the unfettered Mississippi River over the course of unknown centuries, Terrebonne Parish’s fertile land was fed by siltation from Bayous Lafourche and Terrebonne, both distributaries of the Mississippi. On the western limits of the parish, the same scenario occurred through delta-building action of the Atchafalaya River, which is itself a powerful distributary of the Mississippi.

The arable land thus built by the 1700s was particularly fruitful along the bayous of various lengths that transect the parish, from twenty to fifty miles long. The most important of these is Bayou Terrebonne, 50 miles in distance from its headwaters at Bayou Lafourche to Sea Breeze at the Gulf of Mexico. Fertile land rested along these bayous which were hugged by high headlands that tapered downward to swamps and wetlands on both banks. Each bank generally had a “strip of high ground from a quarter to one mile in width”1 parallel to the bayou.

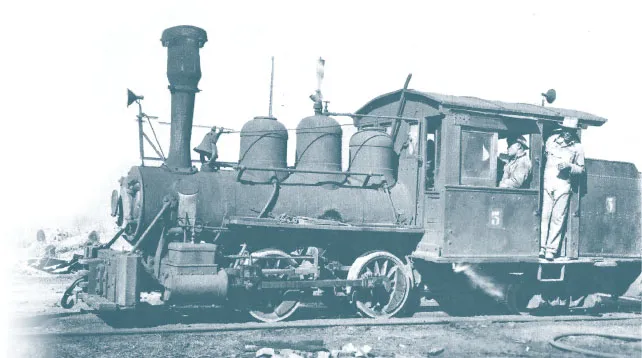

While this geography could have been limiting in the relatively narrow widths of acreage friendly to cultivation along the bayous, the landscape more than made up for that limitation by existence of the natural waterways that allowed shipping of produce by flatboat, and, farther upstream, by steamboats. This was imperative at the beginning of sugar cane cultivation, especially, since adequate roadways were nonexistent in the coastal parish during early settlement. Bayous also served as natural drainage for arable lands along their banks.

However, one source wrote that the head of Bayou Terrebonne, “as were those of the other area bayous, Blue, Petit Black, Chacahoula, was silted over long before the coming of the white men.”2 Just as the Mississippi fed the Lafourche and the Lafourche fed the Terrebonne in the long-ago geological past, Bayou Terrebonne was the source of all the major bayou waterways in Terrebonne Parish. Those that had their direct source from Bayou Terrebonne are Bayou Black (Little and Big), Bayou Grand Caillou, Bayou Little Caillou, Bayou Cane, and Bayou Pointe-aux-Chênes. Bayou Black, in turn, gave rise to Bayou Buffalo (Dularge) and Bayou Chacahoula. Bayou Blue had its source from Bayou Lafourche and paralleled Bayou Terrebonne for a distance, but it is not a distributary of the Terrebonne.

Potato farm Bayou Black 1920

The Sugar Harvest, A.R. Waud Harper’s Weekly, 1875

First recorded inhabitants of the area were the Native American Houmas tribe which had drifted after 1784 into what was to become Terrebonne3. A few hardy French families, “principally from the older colonies of Louisiana,” inhabited the lower reaches of the parish by the late 1700s4, establishing their homesteads not far from the Gulf of Mexico coast. Possessors of land grants who had received them for service in the Revolutionary War when Louisiana was a Spanish colony, and some for other reasons, also settled there. Others, many of them Acadians from Nova Scotia, traversed neighboring Lafourche and St. Mary parishes to settle along other Terrebonne bayous in what was then known as the Lafourche Interior.

Historian Alcee Fortier listed the first settlers of Terrebonne Parish as Royal Marsh on “Black bayou,” the “Boudreaus” on Little Caillou and the Terrebonne, the Belanger family along lower Terrebonne, Prevost, who “started a plantation on Grand Caillou,” the “Shuvin [Chauvin] family on Little Caillou, the “Marlboroughs” in the northern part of the parish, and other sections’ settlers Curtis Rockwood, the D’Arbonnes, LeBoeufs, Trahans, Bergerons, R.H. and James B. Grinage near Houma.5

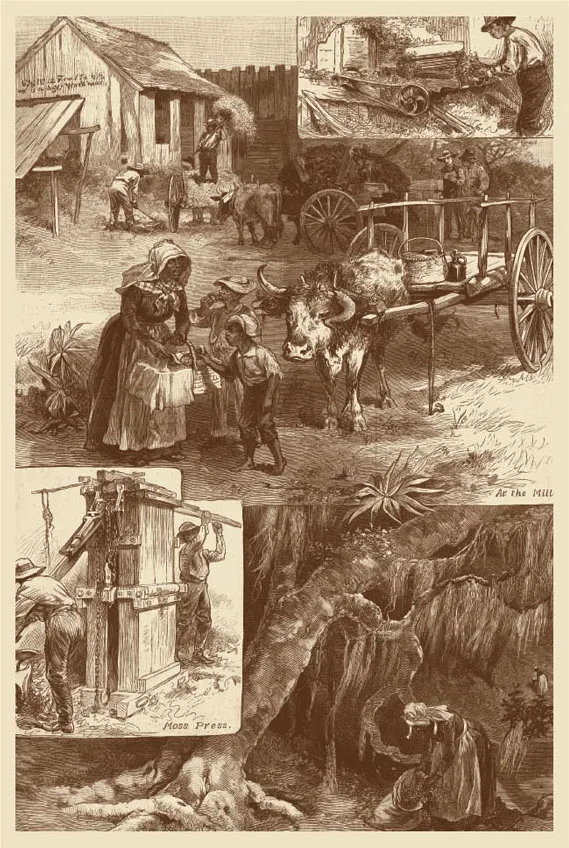

The Moss Industry in the South, Harper’s Weekly, 1882

Those people were overwhelmingly Acadians (Cajuns) who had been expelled from Nova Scotia for not swearing allegiance to the English monarch, and some Creoles (Louisianaborn descendants of European ancestry), with a sprinkling of “Americans, Spaniards and Germans.”5

The great majority of inhabitants until the second quarter of the 1800s were subsistence farmers who grew cotton, corn, rice, peas and fruits of all kinds. Adequacy, not bounty, seems to have been the status quo in Terrebonne from its early settlement in the last days of the 1700s. It took almost two decades after New Orleans planter Etienne de Boré achieved granulation of sugar in 1795 for the parish to begin cultivation of the white gold with which the local area was so identified for more than a century, and which has a healthy presence even today.

Negro cabin Terrebonne Parish c. 1900

At one time in the bayou-webbed civil parish, more than 100 plantations, many of them each worked by only one man and his family, hugged the water transportation corridors fanning out from the parish seat in all directions. Most were of modest acreage on properties abutting each other from bayou headlands.

But as the parish grew, the countryside was made majestic by the unbroken view of verdant fields in an area renowned for its status in the state’s Sugar Bowl. The sheer expanse of waving greenery can be imagined from the fact that in its agricultural heyday, 1830s-1920s, the civil parish was then the largest of the state with its 2,080 square miles, larger than the entire state of Delaware.

Terrebonne’s vast reaches of pristine arable land later became a magnet for more materially ambitious planters from points north and east who settled in Terrebonne to amass sweeping estates. Some locals, and many newcomers, developed sugar estates and large, even grand, homes. The architecture of their homes ranged from Greek Revival to Queen Anne to Louisiana Raised Cottage, to Eastlake, to Colonial Revival, to early Victorian styles, adorning the bayou landscapes among their fields.

Among findings of the 1850 U.S. Census is that Terrebonne Parish was the site of 550 dwellings that year, mostly families. Population was totaled for persons who lived along the various bayou corridors of the parish. Bayou Terrebonne had 1149 people along its banks; Bayou Black, 906; Bayou Little Caillou, 717; Bayou Grand Caillou, 109; Bayou Dularge, 77; Bayou Pointe-aux-Chênes, 27; Bayou Bleu, 22; Bayou Grand Coteau, 18.

Southdown Engine #5 c. 1920

By far, Terrebonne farmers (302) and laborers (223) exceeded the numbers of other occupations, according to 1850 U.S. Census figures. Not surprisingly, overseers, carpenters, and coopers (44, 42, and 36, respectively) were the next most numerous occupational group, since those jobs were vital to plantation operation.

After the Civil War, estates were broken up and sold off, either by owners or the Freedmen’s Bureau. Many stately homes were abandoned, and owners moved away. The sugar farmers who survived were, for the most part, producers with small estates whose families had traditionally worked the land themselves, not relying on slave labor. Mosaic sugar cane disease finished off many planters in the early part of the 20th century.

It is important to know that only a few substantive reminders of Terrebonne’s once-eminent status in national sugar production remain, and whereas at one time sugar houses were common on almost every plantation, not even one sugar house still exists in the parish. This, in spite of the fact that sugar cane remains the dominant local crop.

By 1901, twenty-three gas wells had been drilled in Terrebonne Parish, thereby marking the beginning of the shift from white gold’s dominance to that of black gold in the local economy. Oil and gas production reached its zenith locally in the mid-1900s and beyond.

Today’s residents who drive past Honduras School on Grand Caillou Road, Greenwood School at Gibson, and St. Bridget Catholic Church in Schriever may not be aware that those places are among vestiges of “high sugar” days, surviving only through names that once signified different land owners’ holdings.

Lirette Field blowout 1908

Communities identified on signage or by locals as Hallelujah, Peterville, Levy Town, and other ...