![]()

CHAPTER 1

Water Falls

Falling water has always excited the emotions. Thundering waterfalls and roiling rapids have filled hearts with both dread and wonder from time immemorial. Such fearsome places, where a misstep led to certain death, were thought by many peoples around the globe surely to be the abode of the gods. In the Christian era, it was believed that these were sites of revelation where God made manifest his enormous power, casting human pretensions in pitiful perspective. For millennia, human beings approached waterfalls with a sense of fear, awe, and wonder.

In the modern era, the power of falling water has also stirred another human emotion, ambition, inspiring ingenious thoughts on ways of using some or all of that power for human purposes. The aesthetic of the sublime associated with sites of spectacular nature was gradually displaced in the case of falling water by utilitarian thoughts guided by mechanical engineers and, subsequently, hydroelectric technology. How could that energy, now perceived to be going to waste in conspicuous display, be converted to productive human ends? How could the genie bottled up in nature be released to be re-employed in the service of humanity?

Millers led the way, creating millponds and rechannelling flows in ever more efficient ways to turn their water wheels and crank their machinery. At the larger sites of falling water, millers could use only a small portion of the energy available with their mechanical technology, but at places like Lowell, Massachusetts, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, extensive hydraulic engineering works recovered a large proportion of the available energy to power textile mills, flour mills, and other manufacturing enterprises.1

Hydroelectric power – a more efficient process that could be developed on a larger scale, producing a much more adaptable form of energy that could be used at a distance – rapidly displaced mechanical technology at the end of the nineteenth century. After the physics of electricity was worked out in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, it was left to tinkerers like Edison and Tesla of the late nineteenth century, and then the electrical engineers and capitalist entrepreneurs, to work out, manufacture, and distribute the integrated system to produce, transmit, and then use electrical power. Long-distance transmission proved to be one of the key elements of this integrated technological system, allowing power to be generated in one place but consumed with minimal transmission losses dozens, hundreds, and eventually thousands of kilometres away. Previously, energy users had to locate themselves at sources of power, or power production had to take place close to sites of consumption. Long-distance transmission broke the bond between production and consumption. Henceforth, industry did not have to go to power; power came to industry.2

In Europe and the Americas, electrical power generation, either by steam power or by hydraulic means, was well understood and widely exploited commercially by the beginning of the twentieth century. Large corporations produced, sold, and installed the equipment to generate, transmit, distribute, and consume electricity for a variety of purposes: domestic, commercial, electromechanical, industrial, and traction. Following the relentless logic of returns to scale, electrical systems and generation facilities sought ever larger power sources to generate electricity at the lowest cost and maximum efficiency.

Under this new intellectual and commercial regime, the energy of falling water could gradually be rechannelled through machines all over the world. Waterfalls went silent, or were greatly diminished. Dams across rivers drowned rapids in slack-water lakes as vast quantities of hydraulic energy were converted to electricity to light up the night, energize factories and transportation, and perform a host of mundane domestic tasks. The subdued hum of whirling turbines and generators replaced the thunderous roar of waterfalls and rapids. This new hydroelectric doctrine, which subjugated falling water and transformed hydrology, took root nowhere in the world more firmly than Canada, with its abundant and widely distributed waterpowers. Canada quickly became one of the most aggressive developers of hydroelectricity in absolute quantities, on a per capita basis, and as a proportion of its total energy production mix – an international ranking that it retains to this day.3 Canada got the hydroelectric religion.

And so, eventually, did southern Alberta. With the rise of a significant urban population at the end of the nineteenth century, hydroelectric thinking descended upon the Bow River with all of the evangelism, restless drive, and impetuosity characteristic of western ambition. Calgary’s early experience with electricity mirrored in a microcosm the development of the technology more generally. The first steam-powered electric generators sprang up in the city, close to the hotels and businesses and street lights they served. Then, also in the city, a small dam across the river, primarily for a sawmill raceway, raised water levels to power a low-head hydroelectric-generating facility. With the advent of long-range transmission and under the inspiration of iconic projects at Shawinigan, Niagara, and many other Canadian waterfalls, the entrepreneurial search for electrical energy to empower a burgeoning urban industrial society turned toward the upper reaches of the Bow, where several spectacular cascades advertised its hydroelectric potential.

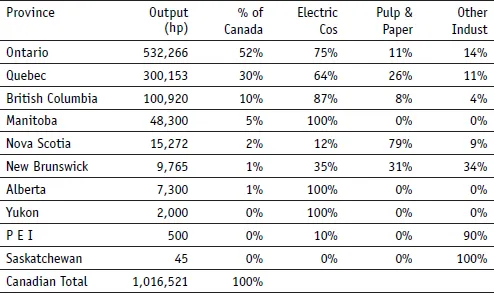

The first reasonably comprehensive survey of hydroelectric development in Canada in 1910, a heroic example of inventory research conducted for the Commission of Conservation by Leo G. Denis and Arthur V. White, helps us place the Bow River developments in their contemporary context.4 This snapshot of the Canadian hydroelectric industry in its infancy counted 960 waterpower sites across Canada, not including an unknown number of unsurveyed locations in the far North. Denis and White identified hundreds of hydroelectric installations operating or under construction, with a total output of a little over a million horsepower (hp), or 740 megawatts (mw). Most of these were small, low-head stations producing a few hundred horsepower and serving mines, sawmills, factories, electric companies, and municipal electric utilities. A few, associated with pulp and paper mills, generated in the range of several thousand horsepower. Two projects at Shawinigan and Niagara Falls were world scale at over 100,000 hp each. Scale mattered more than the sheer number of projects. Only thirty-three large projects (over 5,000 hp) accounted for 79 per cent of total Canadian output. In 1910, electric companies, mainly privately owned, distributed approximately 75 per cent of this hydroelectricity to towns and cities for commercial, industrial, municipal, and domestic uses. A few municipalities close to waterfalls operated their own small plants. Pulp and paper companies and other industries equally divided the remaining 25 per cent of the hydroelectricity. Provincially, Ontario led the way with 53 per cent of total Canadian output, followed by Quebec, British Columbia, and Manitoba. All of the other provinces had less than 10,000 hp under development in 1910. Alberta, with 1 per cent of the national output, was thus just getting into a game already well under way in the East and in British Columbia. Significantly for us, Alberta’s total was accounted for by a single project located on the Bow River.

To look ahead just briefly, Canadian hydroelectric fever would continue unabated in the decades to follow. Despite World War I, hydroelectric capacity would almost double in a decade. It would virtually triple during the 1920s, creating, as it turned out, serious oversupply problems for the industry during the Depression, when hydroelectric development had to be severely reduced. During the 1940s, a global war hampered development, notwithstanding the fact that electricity had become a major weapon of war. Postwar economic growth unleashed another hydroelectric building boom during the 1950s, when capacity once again more than doubled. Hydroelectric capacity growth would ease off during the 1960s, as the engineers ran out of easily accessible rivers. Nevertheless, hydroelectric expansion would continue, albeit at a slower pace, to the present day by exploiting more remote sites in the far North.

The engineering of the Bow River for hydroelectric development would, to a large extent, mirror the broader Canadian experience. As the first run-of-the-river projects became fully operational during the second decade of the twentieth century, growth rates spiked above the national figure. During the 1920s, the system on the river doubled its capacity, but during the Great Depression, not one new hydroelectric project on the Bow came online. The contraction on the Bow was more severe than the national average. Expansion picked up slightly again under the stimulus of World War II, after which the 1950s witnessed a major explosion of developments that slackened off considerably during the 1960s. By then, the Bow, like many other rivers in Canada, had been dammed, plumbed, machined, and wired to its maximum, and Calgarians, along with other southern Albertans, would have to look elsewhere to satisfy their electricity dependence.

Hydroelectric Development in Canada in 1910

Source: Leo G. Denis and Arthur V. White, Water-Powers of Canada (Ottawa: Commission of Conservation, 1911), 22a.

Installed Hydroelectric Capacity in Canada, 1910–1960 (in thousands of hp)

| | Installed Capacity | Growth Per Decade |

| 1910 | 1,011.0 | |

| 1920 | 1,754.1 | 173.5% |

| 1930 | 5,114.1 | 291.6% |

| 1940 | 7,576.1 | 148.1% |

| 1950 | 11,029.8 | 145.6% |

| 1960 | 25,019.3 | 226.8% |

| 1970 | 38,793.6 | 155.1% |

Source: Historical Statistics of Canada, 1st ed., Series P1-6; 2nd ed., Series Q81-4.

Bow River Hydroelectric Development, 1910–1970 (in kw)

| 1910 | 7,000 | |

| 1920 | 23,900 | 341.4% |

| 1930 | 51,900 | 217.2% |

| 1940 | 51,900 | 100.0% |

| 1950 | 82,800 | 159.5% |

| 1960 | 234,200 | 282.9% |

| 1970 | 320,000 | 136.6% |

Source: Calgary Power and TransAlta Annual Reports, see Appendix.

But all of this did not just happen passively. These facilities had to be designed, financed, and built, and their output sold. They were thus driven by a capitalist imperative. Similarly, powerful social forces lay behind the rising but variable demand for electricity, which the developers strove to meet. Technological necessities, especially the need to increase the output of expensive capital equipment to the maximum capacity, demanded further action. The energy of the river was also perceived to be the “property” of other actors; this property had to be politically re-appropriated in favour of the power developers. None of this would be easy, nor was any of it inevitable. Electrification of a city had profound environmental, social, and political implications far beyond its borders. In the process, Banff National Park became a hydroelectric storage reservoir. Such was the power of the hydroelectric religion, capitalism, and urban growth, and the momentum of path-dependent technological development. This story of hydroelectric development on the Bow River, a tale that eventually involved a replumbing of the river to meet the requirements of the technology and the demand for energy, takes us into the fundamental questions of power in a democratic society: Who gets what? Who decides? Who pays?

Blame it on Calgary. Without the mushrooming of a major urban centre in southern Alberta, the Bow, like the other rivers flowing off the eastern face of the Rockies, would not have been extensively engineered. For three decades after its founding in 1875 as a North West Mounted Police post at the confluence of the Elbow and the Bow, Calgary’s growth from a handful of residents to 4,152 in 1901 was far from spectacular. The arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1883 reoriented activity to the more expansive real estate possibilities of the open prairie, but the town remained primarily an unremarkable regional distribution centre for agriculture and commerce. Its energy demands, mainly for street lighting and commercial and industrial power, were slight but not inconsequential and could, for the most part, be handled locally.5 Typically, major industrial power users – hotels, retail stores, and of course, municipalities for street lighting – provided the main stimulus to the development of the electric industry and often organized the companies themselves. Within just three years of the time that Calgary secured municipal incorporation in 1884, its council approved a proposal to light the streets electrically from the small locally owned Calgary Electric Company. Employing a small steam-powered generator, this undercapitalized and badly managed business made more enemies than friends with its intermittent service. Antipathy to the Calgary Electric Company opened the door to competition.6

The Eau Claire Lumber Company, organized by itinerant Wisconsin businessmen who had moved to Calgary, had set up shop on the Bow River just north of the town in the mid-1880s. It conducted logging operations on its timber leases located in the mountains in the upper reaches of the Bow River system, and in classic Canadian fashion, it floated its logs in an annual spring drive to holding booms at its steam-powered sawmill in Calgary. To create the ideal ponding conditions at the mill, the Eau Claire Company acquired the right to build a dam across the Bow just upstream from Calgary in order to redirect water into a channel between Prince’s Island and the company’s mills on the south bank of the Bow. This dam created the conditions for a low-head hydroelectric installation at the outlet of this channel.7 Needing power for their mill, the Eau Claire partners built a small hydroelectric plant with enough capacity to serve other customers as well. With its steam plant and this hydro installation, Eau Claire, under the name Calgary Water Power Company, took over electrical distribution from the moribund Calgary Electric Company.8 By the beginning of the twentieth century, Calgary had recapitulated the history of the electric industry: first came a centrally located steam-powered direct current system mainly for street lighting; then, a small hydroelectric alternating current system exploited local power resources – the slight drop in the level of the Bow Riv...