![]()

John C. Parkin in Conversation with Michael McMordie

Transcribed by Julie Sribney with biographical details provided by Geoffrey Simmins

In the late winter of 1975, Michael McMordie conducted three conversations with John C. Parkin – two at his home on The Bridlepath in the former city of North York, at the northern edge of Toronto, and the other at his Front Street office. The Bridlepath house was designed by Parkin and embodied his most firmly held design principles: classical elegance and quality and a degree of universality – he saw this as reflecting Mies rather than Gropius. Sadly, after his death the property was sold and the house demolished to make way for a much larger and more sumptuous residence completed in 1989.1 Some topics and themes recur through the interviews as they move through different phases of Parkin’s education and experience.

The first of these, conducted 27 and 28 February at the Front Street office, provides the most information about Parkin’s early life, education and career. This is the interview we chose for the book. Parkin reviewed the transcript and added extensive notes and corrections to it.2 We are grateful to Julie Sribney, a graduate architect from the University of Calgary, for having puzzled through the typescripts, Parkin’s amendments, and Michael McMordie’s occasional corrections.

This interview provides insights into John C. Parkin’s personal life and his professional and personal relationship with John B. Parkin (including their steadfast commitment to design only modern buildings) and also presents valuable details about working on two iconic Toronto buildings – the Toronto City Hall (designed by Viljo Revell [1910–1964] and opened 1965) and the Toronto Dominion Centre (also known as the TD Centre), 66 Wellington Street West, Toronto (designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe [1886–1969] with collaboration from Parkin.)3 The Toronto City Hall (architects Viljo Revell and John B. Parkin Associates, 1965) was the product of a highly successful international competition (1957–58) that attracted 532 entries from around the world and was won by Finnish architect Revell. A minority report suggested that the two-tower arrangement was functionally impractical, but the building has been a great popular success. The curved towers and circular council chamber created instantly recognizable shapes, unlikely to be lost among the rectangular commercial office buildings of the downtown. The elevated walkway around Nathan Phillips Square in front of the building clearly defines this space, at the expense of interrupted views inward and outward. As picturesque in its way as E. J. Lennox’s sandstone and terracotta old City Hall (1886–99), Revell’s building is a fitting neighbour and successor.

One of the other interviews deals with Parkin’s architectural education at the University of Manitoba and at Harvard with Walter Gropius and others. It also covers his early experiences of practice and his formation of the Toronto practice jointly with John B. Parkin.

The last discusses John B. Parkin’s move from Toronto and the creation of the Los Angeles firm. That decision led in due course to the end of the Toronto John B. Parkin practice, the creation of the successor firm, Neish Owen Rowland and Roy (NORR), and of John C’s independent practice: Parkin Architects and Engineers. It also touches on the founding of the Canada Council and the National Design Council, among other topics.4

JCP We had few very large commissions until contemporary architecture in Toronto had been sanctioned by officialdom by the world competition for the design of the City Hall. Our task was a very difficult one. We received some recognition earlier, but certainly things began to fall into place from 1956 to 1958. We’re at about mid-point in my professional life; let’s go back to the beginning. Where would you like to start?

McM Well, just for the record and since I don’t have it anywhere else, can you tell me what school in Winnipeg, the University of Manitoba?

JCP I happen to have been born in England of Canadian parents. I’m a double Parkin. My mother’s name was Parkin and obviously my father’s name was Parkin. Their ancestors were related in the eighteenth century. The name itself, which is of the same ultimate origin as Perkins and Peterkin, means son of Peter. Our family originally came from the Derbyshire and Yorkshire border country. We traced the genealogical tree back to the sixteenth century through the College of Arms. My family came to Canada in 1829 and settled under Crown Grant of George IV in what was to become Victoria County (1861–63) on the outskirts of Purdy’s Mills, now Lindsay, Ontario, and near the Scugog River.5 We know the location of the original log cabin of my great-great-grandfather, Samuel Parkin. My brother has the Crown Grant, which was unearthed quite accidentally in a farmer’s attic nearby. Most of us have been buried since in Riverside Cemetery in Lindsay.

Ours is a very cohesive family. My father was a chartered accountant; in fact, he was made a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Great Britain at a very young age. I think he was 30. My grandfather, the son of a clergyman, was also a chartered accountant and a Fellow of the Chartered Accountants Institute of England and Wales. He was admitted as a chartered accountant on July 17, 1886. I have certificates to indicate that he must have been among the first chartered accountants in the world. His certificate was signed by a Mr. Deloitte, subsequently Lord Deloitte and founder of the international firm of Deloitte, Haskins and Sells. The two lines of Parkin, my maternal and paternal sides, came together when my father and mother married in 1914, after a gap of, if I recall, some ten generations. They were very remotely related but with a degree of consanguinity which would not be too dangerous! My background has been entirely a professional one in the paternal line. Parkin & Co. were chartered accountants with offices in England as well as in Canada prior to World War I. The Parkin Lumber Co. in Canada was operated under timber limits Victoria County and Highlands. Log booms were brought through the Kawartha Lakes system when that area was a significant logging country in the mid to latter part of the last century. I suppose therefore that I have a certain business stream as well as a professional one. My brother, who is a year and a half younger, is the Chief Training Psychoanalyst for Canada. He is a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto and in private practice.

It is out of this kind of background we came. In one article, some reference is made to a social consciousness or awareness on my part, which I would like to believe gives me some concern for that particular aspect of architectural practice – certainly as I’ve written about it. I consider it to be of equal importance to the formal and visual implications of architecture. If such an awareness exists, I owe it to my staunch Methodist forbearers, who believed that there was a social obligation on the part of anyone who had the opportunity to return some of life’s rewards. In an article in Maclean’s Magazine, I said that such a consciousness was really owed to some influences at the University of Manitoba. If that was so, I would only hasten to now add that it was merely heightened there, for the kind of design training we had was most certainly not one of social advocacy. I think in the more than fifteen years since that particular article was written by Mr. Phillips (a copy of which you now have), I now think it goes back a great deal earlier than that.6 All our family concerns had to do with one’s contribution to life. I don’t want to be pretentious about it, but I do think it’s important that very early on in life I decided that I did not want to become a chartered accountant; I did not want to follow the family business which had been established in the 1880s, or to enter any of the other fields that my family may have had been involved in at one time or another. My brother made his mind up quite independently, and decided to follow a medical career. I entered the University of Manitoba in 1939 and graduated in 1944 with honours. I then came to Toronto and worked for the then firm of Marani & Morris as a kind of “interim or holding action,” but with the clear notion that I would go on to Harvard.7 I had already been awarded two, possibly three, Harvard scholarships or fellowships. I came to Toronto with Harry Seidler [1923–2006] – he to work for William Somerville, now the firm of Somerville, McMurrich & Oxley.8 Both of us were of one mind – that this was merely a bridging action while arrangements were made so that we could not only enter the United States as students but also work there briefly. It wasn’t easy for Canadians to work in the immediate post-world war period in the United States.

In the meantime, I had heard of John B. Parkin through one or two buildings he had published somewhat earlier. He has also heard of me as I had been a student at the University of Manitoba. We met in Toronto on, I think, the corner of Bay and Bloor, and were introduced in front of what is now the Manulife Centre. We had lunch subsequently, whereupon he offered me a job. He asked what I was making at Marani & Morris and I said $35 a week. He then told me that he had his first school project in Oshawa – a twelve-room school – the largest project he had ever done, and he asked if I could come over and help him design it or if I would in fact design it. I said I would be delighted. I think it was a distinct case of the blind leading the blind. In any event, I left Marani & Morris and joined John B. as an employee at $40 a week, and there began what has become a lifetime association. We have no true legal relationship now but we do have an affiliation. He was in Toronto for three days last week [that is, February 1975]. We are in the process of restructuring an international affiliation in a legal sense, but purely for the exchange of personnel, technical information and that kind of thing – very much the way the international auditing firms work. Both by virtue of our wish that this firm be fully Canadian owned and his quite similar nationalistic concerns, it’s disadvantageous for either of us to have a nominal or minority participation in each other’s firms.

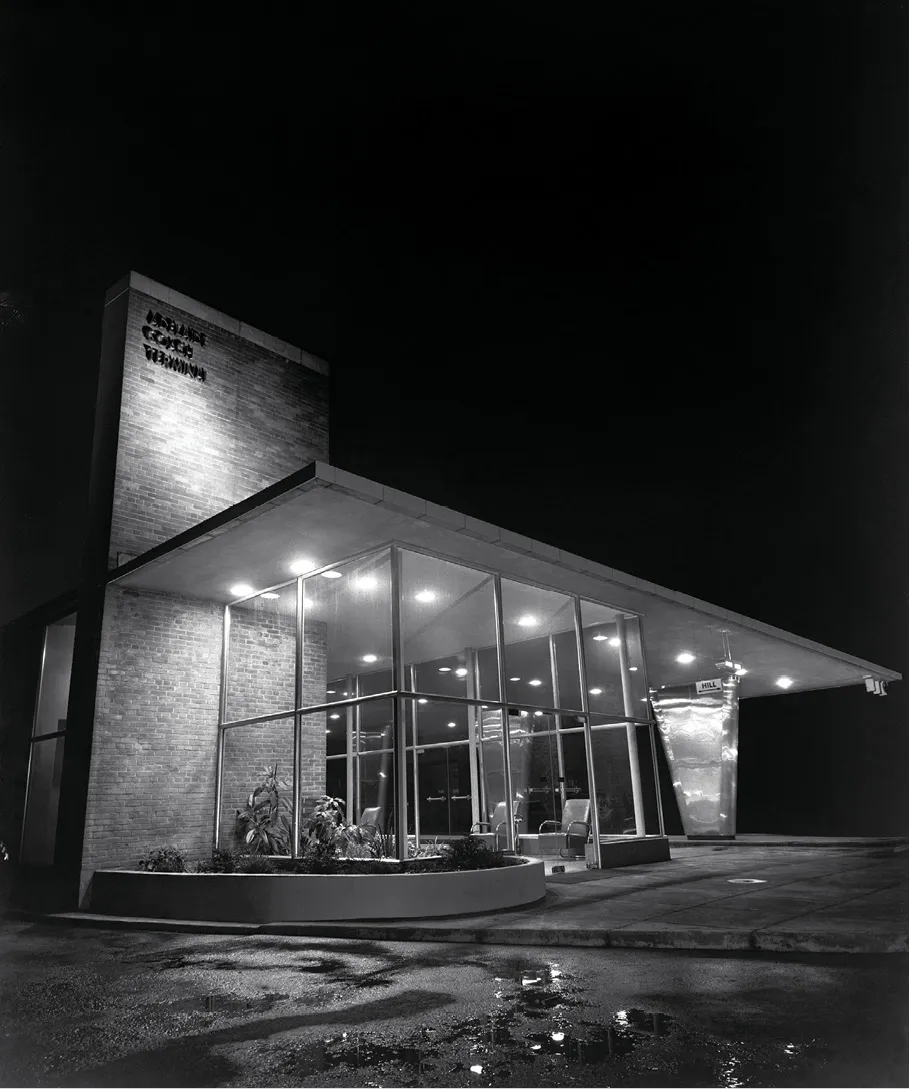

To return some thirty years. I went to work for John B. and found, as we had suspected, that our capabilities and aspirations, in architecture at least, were somewhat different. John was an avowed businessman, but a man of extraordinary moral scruples and of the highest ethics. By religious background he is a Christadelphian, which means that he is lay-minister of his church and a biblical fundamentalist. Therefore, his attitude towards the conduct and practice of his professional life is of the highest and similar to the ideals of my own background. We agreed that we would eventually form a partnership. I was only 22 however. I had left Marani & Morris in October 1944 to join John, who was eleven years older. We agreed, I at 22 and he at 33, to form a partnership. Although we had won our first private competition (for the TTC Adelaide Coach Terminal, since torn down for the Board of Trade Building on Adelaide Street), (figs. 6.1–2), it was jointly acknowledged that I needed design training of the highest calibre and that I should take advantage of the Harvard scholarships. This I wanted to do in any event.

6.1. Toronto Transit Commission Bus Terminal, Bay and Adelaide, Toronto. Panda Associates fonds, Canadian Architectural Archives (PAN 47645-7k).

6.2. Toronto Transit Commission, Bus Terminal,

Toronto, Panda Associates fonds, Canadian Architectural Archives (PAN 4611-1).

I went to Harvard in January 1946. It was a very exciting period of time to be at Harvard. Within the first month or so of my arrival, I. M. Pei [1917– ] presented his thesis. He had taken his undergraduate degree at MIT, and was finishing his master’s and presenting his thesis. It was a marvellous thing to audit a jury consisting of Marcel Breuer [1902–1981] and Hugh Stubbins [1912–2006] and, above all, Walter Gropius [1883–1969].9 Some of us were very young and impressionable. To see so many of the names familiar to us, in one room at one time, was a delightful thing. Breuer declared Pei’s thesis the finest...