eBook - ePub

Formalise, Prioritise and Mobilise

How School Leaders Secure the Benefits of Professional Learning Networks

- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Formalise, Prioritise and Mobilise

How School Leaders Secure the Benefits of Professional Learning Networks

About this book

Professional learning networks (PLN) of teachers and others (such as university researchers) collaborating outside of their everyday community of practice are considered to be an effective way to foster school improvement. At the same time, to generate change, PLNs require effective support from school leaders. Such support should be directed at ensuring those participating in PLNs can engage in network learning activities; also that this activity can be meaningfully mobilised within participant's schools. What is less well understood however are the actions school leaders might engage in to provide this support.

To address this knowledge gap, this book presents a case study of how senior leaders attempted to maximise the effectiveness of participating in PLNs for one learning network: the New Forest Research Learning Network (RLN) - a specific type of PLN designed to facilitate research-informed change at scale. In-depth semi-structured interviews with RLN participants, as well as impact data and policy documents, have been used to ascertain the types of leadership practices employed and their nature (i.e. whether geared towards prioritising, formalising or mobilising the work of the PLN). Also presented is an assessment of the perceived effectiveness of these practices and suggestions for the type of leadership activity that appear to maximise the effectiveness of schools engaging in professional learning networks more generally.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Formalise, Prioritise and Mobilise by Chris Brown,Jane Flood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE EMERGENCE OF PROFESSIONAL LEARNING NETWORKS

In the current international policy environment, teachers are viewed as learning-oriented adaptive experts. They are required to be able to teach increasingly diverse sets of learners, and to be knowledgeable about student learning, competent in complex academic content, skilful in the craft of teaching and able to respond to fast changing economic, social and policy imperatives (de Vries & Prenger, 2018; Schleicher, 2012). It is clear, however, that the entirety of the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed for this complex teaching profession cannot be developed fully through the provision of initial teacher education programs alone (de Vries & Prenger, 2018). Collaborative career-long learning is therefore required. It is also apparent that ‘[t]he increased complexity of a fast changing world has brought new challenges for schooling that are too great for those in any one school to address by itself’ (Stoll, 2010, p. 4). The rise of these challenges has been coupled with an increased emphasis worldwide on education systems that are ‘self-improving and school-led’; with a concomitant focus on school leaders to drive forward school improvement (Greany, 2014). In response, educators and policy makers are increasingly turning their attention to networked forms of teacher learning and professional development as a preferred way of improving education provision (Poortman & Brown, 2018). For example, Armstrong (2015) suggests the move towards networked collaborative learning as a means of improvement is prevalent in a range of countries including: England, the United States, Canada, Finland, Scotland, Belgium, Spain, India, Northern Ireland and Malta.

While the focus on networked forms of professional development is evident amongst policy makers (OECD, 2016), it is similarly reflected in academia. Here educational researchers, such as Hargreaves (2010), Greany (2014) and Stoll (2015), argue that learning networks are fundamental to achieving effective educational improvement. What is more, educators learning, both from colleagues and others (e.g. university researchers), is considered an effective way to support teachers in rethinking and improving their own practice (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008). Learning networks would thus appear to provide the opportunity to achieve cost-effective educational innovation and enhancement at scale (Greany, 2014; Hargreaves, 2010; Hargreaves & Shirley, 2009; Munby & Fullan, 2016). As a result, it is argued that efforts at school improvement should now be framed within a broader context, moving from the school as a single unit to considering the connections between schools, central offices, universities and others in networks (Finnigan, Daly, Hylton, & Che, 2015; Greany, 2014; Stringfield & Sellers, 2016).

WHAT ARE PROFESSIONAL LEARNING NETWORKS?

Conceptualising the notion of learning networks more formally, Brown and Poortman (2018, p. 1) define Professional Learning Networks (PLNs) as any group who engage in collaborative learning with others outside of their everyday community of practice to improve teaching and learning in their school(s) and/or the school system more widely. Brown and Poortman’s (2018) definition of PLNs is multifaceted and so encompasses a vast range of between-school or school-plus-other-organisation network types. These include research or data use teams, multisite lesson study teams, teacher design teams, whole-child support teams and so on (see Poortman & Brown, 2018). Importantly, PLNs can also vary in composition, nature and focus: they may consist of teachers and/or school leaders from different schools, teachers with local or national policy makers, teachers and other stakeholders and many other potential combinations. In many cases, networks will also form in partnership or involve joint work with academic researchers (Poortman & Brown, 2018).

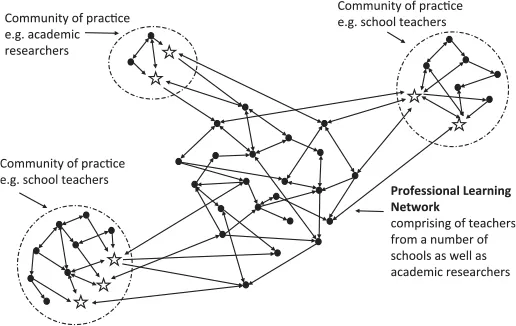

Brown and Poortman’s (2018) conceptualisation of PLNs is set out graphically in Fig. 1.1. Here each black dot or white star represents an individual (e.g. a teacher or academic researcher). The arrows meanwhile represent connections and so flows of information or other forms of social capital that occur between individuals. As can be seen, there are two types of groupings of individuals represented in Fig. 1.1. The first, demarcated by the dotted circles, is everyday communities of practice (e.g. a whole school or subject department or a university department). The second type of grouping – the mass of black dots in the centre of the diagram – represents a PLN. In the three communities of practice presented in Fig. 1.1, the members of the PLN are those individuals who are represented by white stars. Thus, it can be seen that PLNs are comprised of individuals with connections that stretch beyond the dotted circles and into the network of individuals at the centre of the diagram. At the same time, as the number of white stars indicates, PLNs typically comprise a small number of individuals from each community of practice rather than a whole school approach.

Fig. 1.1. A Graphical Depiction of PLNs.

Source: Brown and Poortman (2018).

Source: Brown and Poortman (2018).

Research evidence suggests that the use of PLNs can be effective in supporting school improvement. In particular, studies suggest that teacher collaboration in learning networks can lead to improved teaching practice and increased student learning (Borko, 2004; Darling-Hammond, 2010; Vescio et al., 2008). Such improvements occur because effective learning networks are those that meet the necessary criteria for successful professional development (Desimone, Smith, & Phillips, 2013; Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006). In other words, effective PLNs involve the type of long-term collaboration that enables participants to draw down on the expertise of others in order to develop new approaches to teaching and learning. Nonetheless, despite this starting point that PLNs can significantly contribute to improved teaching and learning, harnessing the benefits of learning networks is not without challenge. In particular, it is noted by Poortman and Brown (2018) that participation in learning networks does not automatically improve practice; the effects can sometimes be small and results have been mixed (e.g. see Chapman & Muijs, 2014; Hubers, Poortman, Schildkamp, & Pieters, in press; Lomos, Hofman, & Bosker, 2011; Prenger, Poortman, & Handelzalts, 2018). For example, research by Hubers et al. (in press) shows how, after external support was withdrawn, schools struggled with implementing the products of the PLN in question, as well as with keeping the PLN itself going. Correspondingly, Hubers and Poortman (2018) suggest that a number of supporting conditions need to be in place before PLNs can be successful (also see Katz & Earl, 2010; Lomos et al., 2011; Stoll et al., 2006; Vescio et al., 2008). These conditions include focus, collaboration, individual/group learning, and reflective professional inquiry. In particular, however, is the vital role of leadership (e.g. see Harris & Jones, 2010; Muijs & Harris, 2003). In the first instance, leadership is required of the networks themselves to ensure that they function effectively (Briscoe, Pollock, Campbell, & Carr-Harris, 2015). Second, however, it is also the role of senior leaders to ensure that there is meaningful participation by their teachers in network activity and that this participation makes a difference within teachers’ ‘home’ schools. Of these two aspects of leadership, it is that latter that is explored in this book.

THE ROLE OF LEADERSHIP IN SUPPORTING PLNS

Extant literature suggests a number of key characteristics have been identified as important in relation to effective leadership, including (Day & Sammons, 2013, 5):

- Providing vision.

- Developing, through consultation, a common purpose.

- Facilitating the achievement of organisational goals and fostering high-performance expectations.

- Linking resources to outcomes.

- Working creatively and empowering others.

- Having a future orientation.

- Responding to diverse needs and situations.

- Supporting the school as a lively educational place.

- Ensuring that the curriculum and processes related to it are contemporary and relevant.

- Providing educational entrepreneurship.

What is less clear, however, is how these characteristics might apply to ensuring that the benefits to schools of engaging in PLN activity are maximised. For example, it is vital that the PLN activity leads to long-term change within participating schools. As Hubers and Poortman (2018) note, this requires a two-way link to be established between the work of the PLN and the day-to-day teaching practice taking place within those schools. This link comprises two aspects: first, to maximise the benefits of being part of a learning network, PLN participants need to engage effectively in networked learning activity. Second, teachers (and other relevant staff) within the wider community of practice will need to know about, engage with, apply and continue to improve the products and outputs of the PLN; ultimately with the aim of improving student outcomes. To achieve such a link, however, requires senior leaders to understand how to meaningfully support both participation within PLNs and the mobilisation of PLN practice by teachers within their school. For example, school leaders need to ensure that for participants, the work of the PLN is prioritised appropriately in relation to other day-to-day demands. Also that resource (e.g. teacher supply/teacher cover) is provided to ensure that PLN work is considered an integral part of, rather than in addition, to the day job (Farrell & Coburn, 2017; Hubers & Poortman, 2018; Rose et al., 2017). Senior leaders also need to understand how mobilisation can be embedded as a part of school culture (e.g. that communication pathways exist: Farrell & Coburn, 2017); how to ensure that mobilisation is facilitated by organisational routines (Farrell & Coburn, 2017; Rose et al., 2017); and understand how to ensure that appropriate support is available. To date, how school leaders support engagement in and the mobilisation of PLN activity within their schools is sparsely reported in the literature. To address this gap in the knowledge base, and to further develop our understanding of the role of senior leaders in maximising the benefits of schools engaging in PLN activity, this book examines a case study of a specific type of PLN: Research Learning Networks (RLN).

RESEARCH LEARNING NETWORKS

The notion of Research-informed teaching practice (RITP) refers to the process of teachers accessing, evaluating, and using the findings of academic research in order to improve their teaching practice (Cain, Wieser, & Livingston, 2016; Walker, 2017). RITP is increasingly considered by many to be the basis for effective teaching and learning as well as for high-performing education systems (Furlong, 2014; Rose et al., 2017; see Gorard & Siddiqui, 2016; Walker, 2017; Wisby & Whitty, 2017). Correspondingly, achieving RITP at a systemic level has become the focus of many school systems worldwide (Coldwell et al., 2017; Graves & Moore, 2017; Wisby & Whitty, 2017). In keeping with the current focus on RITP, RLNs are a specific type of PLN designed to enable the roll out of new RITP at scale (Brown, 2017a). RLNs operate by establishing one (or more) PLNs with participants from a number of schools, then using these participants to generate research-informed practices as part of a series of network workshops. Participants then work with their wider school colleagues to embed these practices in their ‘home’ schools. By way of example, in the first iteration of the RLN model, 14 RLNs were formed, comprising 110 staff from 55 primary schools in England. Here it was intended that this networked approach would ultimately lead to the introduction of new practices amongst some 500+ teachers, benefitting some 13,000 students overall.

There have been some recent criticisms regarding the appropriation of the idea of RITP by those interested in using it as a way to champion the notion of ‘what works’; along with a corresponding privileging of methodologies such as randomised controlled trials and meta-analysis (e.g. see Wisby & Whitty, 2017; Wrigley, 2018).1 It is worth highlighting at this point, therefore, that the RLN approach comes with no inherent focus on research relating to ‘what works’ outcomes, but rather is concerned with helping teachers, schools, and school leaders use a range of research to improve a wide spectrum of outcomes for children. What these outcomes might comprise includes aspects of bildungsbegriff,2 children’s physical and mental well-being and their fortitude, as well as more instrumental notions such as children’s learning and academic performance. These outcomes could be improved through the development of new research-informed practices – which might be regarded as more technical in nature – but also through the development and sharing of new values, concepts, and ideas in relation to the role and purposes of education (which can again be influenced by research, such as comparison studies or theories regarding the purposes of education) and which subsequently affect both the curricula that is developed and taught, as well as the educational environment within a school. In fact, as you will see, in this book, the research foci of the schools involved in the RLN encompasses students’ physical development, their mental resilience, understanding how to engage hard-to-reach parents, boys’ writing, and how to improve the outcomes of summer-born children. In other words, a range of outcomes from those that relate to standardised tests to those that help children engage in education more effectively.

An evaluation of the first iteration of the RLN approach by Rose et al. (2017) suggest that the efficacy of the approach would be improved if school leaders better supported participants to engage with network workshops as well as providing them with opportunities to develop research-informed practices collaboratively with colleagues back at their school. It would seem, therefore, that the RLN model represents a suitable case to focus on in terms of examining the role of school leaders in maximising the benefits of their staff engaging in PLN activity. The specific RLN that forms the focus of this case study comprises 21 staff from eight primary schools situated in the New Forest area of England. It is hoped that the New Forest RLN will ultimately lead to change amongst some 70 teachers and 1,470 students overall. This study focuses on the operation of the New Forest RLN from October 2017 to June 2018. As with previous iterations of the approach, the New Forest RLN is grounded in a number of key processes and ideas.

First, the RLN involved four whole day workshops, which led participating teachers through a research-informed cycle of enquiry. More specifically, the workshops involved a process of learning, designed to help participants develop and trial new practices informed by research and directed at tackling specific issues of teaching and learning in their home school. In keeping with the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Authors

- 1. The Emergence of Professional Learning Networks

- 2. Researching the New Forest RLN

- 3. What Actually Happened Across RLN Schools?

- 4. Exploring the Actions of Individual Schools

- 5. Discussion

- References

- Index