![]()

ONE

THE MOSES ERA

Public sculpture in post-Second World War New York City was rather fallow terrain. Statues and monuments had been an integral part of the turn-of-the-twentieth-century civic landscape, but declined in number during the Depression and Second World War, the outgrowth of professional power struggles and changing artistic styles and aesthetic priorities. Monuments were less civic art, as had been conceived in older days, than decorative accompaniment, often rendered in relief, for Art Deco or more severe “classical moderne”-style buildings. Commentators disavowed figurative statuary as outmoded and disingenuous.1 Some veterans and neighborhood groups attempted to erect war memorials in the late 1940s and early 1950s. However, inter-organizational dissension, and resistance from both the city’s design review body (the Art Commission of the City of New York, ACNY), and from the powerful Commissioner of Parks Robert Moses, meant that little went forward.2 Indeed, when it came to public space and design in general, Moses wielded exceptional influence.

Moses (1888–1981) had a strong civic-minded orientation, but monuments were not necessarily a part of it. As previous commissioners had, he called the shots on what was suitable for placement in New York City parks (where the majority of monuments were situated). In fact, he disliked most public sculpture, regarding it as outmoded, sentimental, and poorly designed; he even penned a two-part New York Times Magazine article expressly to mock it.3 “God help this town,” Moses opined,

if we are to be measured by our monuments . . . The great opportunity to rid ourselves of the monstrosities we inherited has come and gone. The fact is that we just did not have nerve enough to seize it . . . There is no field of municipal government which has more headaches, heartaches, contentions, asininities and humor.4

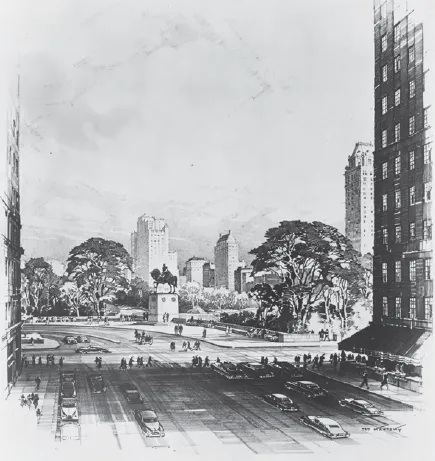

| Sally James Farnham, Simón Bolívar, installation view of Central Park South at Avenue of the Americas, Clarke, Rapuano, and Holleran, c. 1956. |

Sally James Farnham, Simón Bolívar, 1921, bronze; pedestal, black granite (polished), Central Park South at Avenue of the Americas.

Moses rarely took the lead in commissioning work, and there was little money in city coffers in any event. When Moses did have occasion to be involved with new projects, he leaned toward figurative art in a modern archaicizing mode, with simplified, angular silhouettes, rough-ish surface treatment, and muddier brown patinas than New York’s Beaux-Arts-style precedents. When offered sculptural gifts for New York City Parks property, he chose subjects that advanced Cold War agendas or appealed primarily to children. The three “Good Neighbor Policy” equestrian monuments of South American liberators at a newly redesigned entrance plaza of Avenue of the Americas and Central Park South (José de San Martín, José Martí, and Simón Bolívar), as well as Hans Christian Andersen and Alice in Wonderland in Central Park, were representative among them.

Cold War Play Sculpture

The Hans Christian Andersen and Alice in Wonderland statues were notable new additions to Central Park, whose custodians had vigilantly guarded against monumental intrusions. Following a pattern of patronage common in the United States since the late nineteenth century, private groups donated the funds for both statues.5 Thus, for example, the Danish-American Women’s Association of Jackson Heights, Queens sponsored Hans Christian Andersen with monies raised in part from Danish-Americans and children (a well-worn fundraising tactic), in honor of philanthropist and Association founder Baroness Alma Dahlerup.6 Moses was in the process of re-landscaping the eastern interior of the park in the lower Seventies, and was looking for private donors to help underwrite costs.7

As the author of beloved children’s stories, Hans Christian Andersen was a pleasing and suitable subject for that park locale. Along with the model boat basin and Conservatory Pond (a rehabilitation project also underwritten with private money), the statue would create an oasis that would help attract families and residents from posh surroundings such as Fifth Avenue. These populations were a desirable force for revitalization of parks at a moment when urban decentralization was taking hold in New York City and the Department of Parks (DPR) needed money for both capital projects and basic maintenance. Thus when the Danish-American Women’s Association proposed the gift in spring 1955, Moses accepted it with little hesitation.

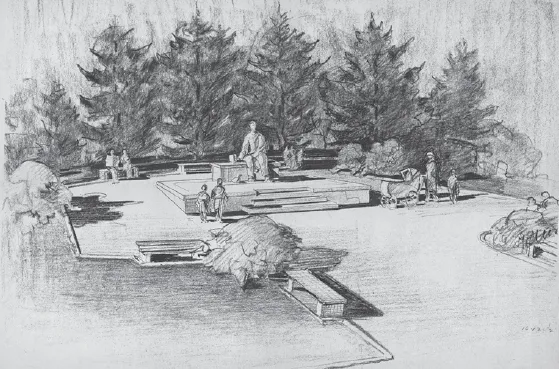

George Lober and Otto F. Langmann, perspective drawing for Hans Christian Andersen monument site.

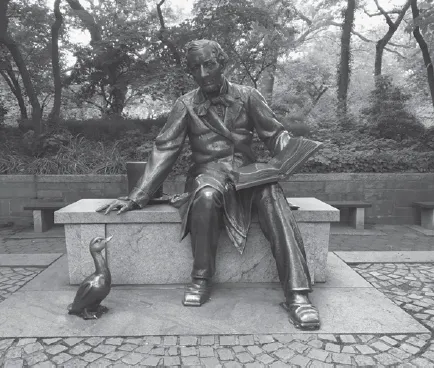

Georg Lober (1891–1961), a traditionalist figurative sculptor, won the commission and set to work. The ACNY, for which Lober worked as Executive Secretary, rubber-stamped the project soon after submission, a fact that did not go unnoticed by astute newspaper critics.8 The statue was dedicated in 1956 (1955 having been the 150th anniversary of Andersen’s death) on the western side of the Conservatory Pond. As intended, it immediately became popular among children, thus contributing to the youth and active leisure focus of city parks that was a hallmark of Moses-era design.9

Georg Lober, Hans Christian Andersen, 1956. Andersen holds a book open to “The Ugly Duckling,” whose bronze likeness stands attentive nearby. The figures are placed atop a low granite platform in a paved and landscaped sitting area near the East Drive at 74th Street, designed by architect Otto F. Langmann at an approximate cost of $73,585.

Moses’s receptivity toward Hans Christian Andersen made sense. Andersen had international renown. The subject advanced Moses’s vision of parks as magnets for children, as did the heartwarming “Ugly Duckling” story of transformation. These associations alone may not have been the only reason that Moses took interest, however. The work also had a subtext with deeper significance that resonated with preoccupations of the Cold War era. Within the context of post-Second-World-War politics, the date and choice of subject were notable. In the wake of the German invasion of Denmark on 9 April 1940, that nation had abandoned its centuries-old position of long-standing neutrality. In 1949 Denmark joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Andersen was thus not just a significant figure within the canon of great children’s literature. He was, as well, for the Danes, identified with the Kingdom of Denmark, a symbol of nation and of ethnic pride.10 Hence the gift to the City of New York signified the unbreachable alliance between Denmark and the United States. It served as an expression of Danish resilience and fortitude and as vindication for the risky political path that that kingdom had chosen to take. As such, the work had a higher purpose, one consistent with the ideals represented by the Latin American liberators whose equestrian likenesses were installed at Central Park’s southern end.

Alice in Wonderland

As Hans Christian Andersen had been, Alice in Wonderland was made possible because its subject was consistent with Moses’s predilection for parks as play spaces.11 Statues depicting beloved fictional characters invited climbing, thus complementing the playgrounds and ballfields that Moses had constructed in great numbers since 1933. The Alice commission represented not only Moses’s preoccupations, of course, but—as was invariably the case with monuments that relied upon private patronage—the self-interests of others: here, those of donor and sculptor. Diverging agendas produced decidedly adult disagreements, although limited enough to be managed by Parks administrators, and hence not ultimately fatal.

Alice in Wonderland did not have the same ideological overtones as Hans Christian Andersen, but as Hans Christian Andersen had, it contributed to the aura of Central Park as a family-oriented playland. Alice in Wonderland as a subject was a departure from statuary traditions, Alice being neither a god nor a hero, but rather a figure from children’s literature. The work was the sculptural counterpart to the popular imaginative renditions that began with John Tenniel’s famed 1865 illustrations for Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and continued on into the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, with the animated cartoons of Walt Disney and the Fleischer studios.12 Sculptor José de Creeft’s interpretation whimsically evoked the famous Mad Tea Party scene (which had a widespread appeal in American culture as a celebration of irrationality), although it did not depict specific text or the Tea Party’s parody of aristocratic pomposity.13 At a moment when pervasive fears about nuclear holocaust prompted occasional bouts of existential angst, the absurdism conjured up by the Alice stories also resonated: not for nothing did the Walt Disney studio return to Alice as a full-length animated feature, released in 1951.

Mythical figures were part of a sculptor’s stock and trade, but most were classical or ideal in nature. Gods, goddesses, and allegorical personifications were still quite prevalent, even in the art of Moses’s era, in works like The Rocket Thrower in Flushing Meadows Park in the borough of Queens.14 Alice in Wonderland was a new departure for its time in depicting specific but fictional characters and stories, a practice seen in the nineteenth-century statuettes of John Rogers and Daniel Chester French, but rarely in the work of twentieth-century sculptors, and certainly nothing on this scale.15

Although the name Robert Moses certainly does not spring to mind when one thinks of the “Mad Tea Party,” Moses was in fact quite interested in the subject and in securing Paul Manship to sculpt it.16 The challenge was finding money, which, according to Moses, the DPR did not have. A Joseph M. Hartfield notified Moses that a Mrs. Martineau was a possible donor, but that for reasons unknown she was unwilling to “employ Manship.”17 Ever the pragmatist, Moses responded that Parks would not dictate the sculptor but would also not select an artist who was likely to be turned down by the ACNY or Parks authorities (like him). “This is a delicate business and leads to endless complications if it is not managed properly at the beginning,” he wrote. “While Paul Manship is a topnotch man for the Alice in Wonderland group, there are certainly half a dozen others whose work would be acceptable.” One of tho...