![]()

1

Navigating the Gray AREA

If you knew what you were doing it wouldn’t be called research.

—Albert Einstein

John Christopher, the founder of a Nepal-based charity called the Oda Foundation, was on his way to breakfast during a family vacation in London on April 25, 2015, when he learned that a massive earthquake had struck Nepal, killing nearly 10,000 and injuring more than double that number.

John had started the Oda Foundation, which provides basic healthcare services to people in the rural village of Oda, Nepal, less than two years earlier after volunteering at a school in nearby Surkhet. He had chosen the remote village of Oda, a 16-hour flight, drive, and hike from Nepal’s capital of Kathmandu, because it had a shortage of resources and John thought he could help. He figured that by providing basic healthcare services—the leading causes of death in Oda were diarrhea and childbirth—he could save a life for as little as $2.23.

His efforts were met with immediate success. In his first year, on a total budget of $25,000, he estimated he had saved roughly 40 lives, making his little startup one of the most efficient healthcare foundations in the world.

When John heard the news in London, he was relieved to learn that his community was outside the earthquake’s deadly range, and his attention turned to a new urgent question: How could he quickly transform his on-the-ground team into a more useful health service provider for Nepal? How could he best serve the health needs of a country that suddenly looked very different from the country where he had operated for the past two years?

He laid out his options in his head. There were three different paths he could follow. Path One: Expand beyond his rural clinic by opening a new health clinic on a main road where his staff could easily service more patients. Path Two: Accept the Nepalese government’s offer to partner with their existing health clinics to expand the government’s treatment and care. Path Three: In a country with such treacherous terrain, invest in drones to drop and deliver medical kits around the country.

Which option should he choose? The strategies were very different from one another. How could he decide which course of action was the right one? He didn’t want to rush to judgment, even though time was of the essence. How could he swiftly arrive at a well-reasoned and researched outcome to make an educated decision for a future that at first glance seemed so unpredictable?

John was faced with a high-stakes decision that would have a long-term impact on the well-being of his foundation and its reputation, a decision that needed to be made with incomplete information amid a volatile backdrop, in a changing environment with an urgent need for medical care.

That’s the problem John came to me with just after the earthquake. We met just days before the tragedy, in the halls at Columbia University’s Business School, where I was co-teaching a course in Advanced Investment Research. For this course, I was using and teaching a research and decision-making process that I’d developed called the “AREA Method,” an acronym that gets its name from the perspectives it addresses. I realized AREA was applicable to John’s problem.

As a journalist, teacher, consultant, mother, sister, wife, daughter, and friend, I’ve learned that there are few absolutes—and many gray areas. We each experience the world differently. I put together the AREA Method as a way to navigate gray areas and avoid those mental shortcuts that enable us to make small decisions easily but may impair our judgment when making big decisions. In short, I was searching for a better way to make big decisions.

In developing AREA, I realized that the process does much more than provide a research and decision-making roadmap; it makes your work work for you. It heightens your awareness to the motivations and incentives of others. It helps you avoid bias in your work and engage with people and problems more mindfully. Decision-making is about ideas, but ideas aren’t enough. There is an important gap between having ideas and making good decisions about what to do with those ideas.

It can be messy and overwhelming to figure out how to solve big problems or make high-stakes decisions. Friends often asked me, “Where do you start? How do you know where to look for information and how to evaluate it? How can you feel confident that you are making a careful and thoroughly researched decision in such a volatile, uncertain world?” I believe the AREA Method will provide you with both the confidence and knowhow to do just that.

The AREA Method has worked for me professionally and for the countless students I’ve taught at both Columbia Business School and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, as well as for a diverse mix of for-profit and not-for-profit clients that hire me for strategy consulting work. But the AREA Method has also changed my thinking. I have found that I’m applying the framework as a way to think about all sorts of personal and professional decisions.

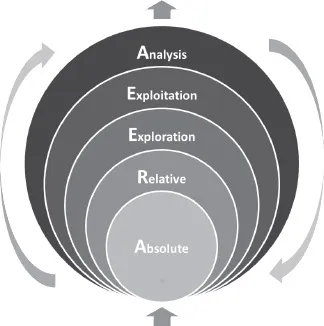

The AREA process gets its name from the perspectives that it addresses: Absolute, Relative, Exploration and Exploitation, and Analysis. The first “A” stands for “Absolute,” which refers to primary, uninfluenced information from the sources at the center of your research and decision-making process. The “R” stands for “Relative,” and refers to the perspectives of outsiders around your research subject. It is secondary information, or information that has been filtered through sources connected to your subject. The “E” stands for “Exploration” and “Exploitation,” and they are the twin engines of creativity—one is about expanding your research breadth and the other is about depth. Exploration asks you to listen to other peoples’ perspectives by developing sources and interviewing. Exploitation asks you to focus inward, on you as the decision-maker, to examine how you process information, examining and challenging your own assumptions and judgment. The second “A” stands for “Analysis,” and synthesizes all of these perspectives, processing and interpreting the information you’ve collected. Each of these steps will be explained in detail in the chapters that follow.

Together the “A” and the “R” provide you with the tools necessary to create a framework for gathering and evaluating information. The latter part of the AREA Method, the “E” and the “A,” provide detailed examination tools gleaned from experts in other fields such as investigative journalism, intelligence gathering, psychology, and medicine.

The AREA Method

AREA is a decision-making process focused on mining the insights and incentives of others to help you manage mental shortcuts. The steps build upon one another, radiating out from the center, and also serve as a feedback loop. The views and insights of other stakeholders are integrated until you fit them together.

AREA helps you make smarter, better decisions by improving upon classic research and decision-making pedagogy in four important ways:

1. AREA recognizes that research is a fundamental part of decision-making.

2. AREA solves the problem of mental myopia—assumption, bias, and judgment in particular—through its construction as a perspective-taking process.

3. AREA addresses the critical component of timing so that you have time for calculated and directed reflections that promote insight, that is, slowing down to speed up the efficacy of your work.

4. AREA provides a clear, concise, and repeatable process that works as a feedback loop in part or in its entirety.

Advantages of the AREA Method

The AREA Method helps you bring greater CARE to making smarter, better decisions.

Craft Critical Concepts

• Your Critical Concepts focus your research and address the driving purpose behind your decision

• Advantage: Keeps you focused on what matters the most.

Address biases

• We bring our assumptions and judgements to the way we view the world.

• Advantage: AREA pre-empts and controls for our mental shortcuts.

Reveal perspectives

• Breaks down the research process into a series of easy-to-follow steps.

• Advantage: Helps you make sense of the insights and incentives of others.

Extract Learning

• Cheetah Pauses “slow down time” to accelerate your work—“strategic stops” in the research process.

• Advantage: Chunk your learning to either forge ahead or loop back into the AREA process.

AREA recognizes that research is a fundamental part of decision-making

In reality, your ability to make a thoughtful decision is dependent upon the quality of the information you have. Therefore, you need a good research process to be an integral part of a decision-making framework. Currently, there are no methods out there that guide you through a research process with respect to making a decision at the end of it.

In fact, the current popular decision-making books and tools often lump the processes of “do research” or “evaluate your options” into a single step. AREA recognizes that research is an umbrella term for a whole series of tricky steps that need to be carefully navigated and thoughtfully completed. AREA breaks down the research so it is not a “black box.” Instead, it’s manageable and organized into an easy step-by-step logical progression.

You may shudder at the idea of doing research, thinking back to painful hours spent in your high school or college library, trying to stay awake as you plodded through musty, outdated books. But the task you face now—making an important personal or professional decision—isn’t like the research process you followed in school; these high-stakes decisions are not closed cases. You’re no longer studying something from the past; you’re planning for an uncertain but important future: yours.

The AREA Method allows you to become your own expert in the ecosystem related to the decision you need to make. In that sense, it’s more than a process that you apply—it’s a muscle that you build and it can become second nature; it can be part of the frame you bring to the world.

AREA solves mental myopia through its construction as a perspective-taking process

Much has been written about how we are all prey to mental mistakes. Behavioral science research and books such as Robert Cialdini’s Influence and Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow explain that we rely on faulty intuition and are swayed by authority and public sentiment, but they don’t give us tools or techniques to overcome our flawed thinking. Instead, this new research explores the many ways that we allow biases, snap judgments, and assumptions to drive our decision-making. Although these pathways help us to make decisions quickly and easily, they impede our ability to think openmindedly and thoroughly about complex problems. In other words, we know our thinking is flawed, but we don’t know what to do about it. AREA gives us a framework to proactively manage these flaws.

AREA moves you from one vantage point to the next, isolating and categorizing information based on its source, enabling you to fully appreciate each perspective’s point of view and the incentives that shape it.

Perspective-taking acknowledges that although you may think that you understand how to solve a particular problem, your understanding of that problem is most likely incomplete and different from how other key players see it. By walking in their shoes, you will better recognize other players’ considerations and incentives. You may even come to understand the facts differently. But the method doesn’t just look closely at what others are doing and perceiving; it also guides you to look inward by taking you through a series of self-assessment exercises. I learned about these exercises from other disciplines including medicine, investigative journalism, and intelligence-gathering. They point out flaws in our understanding of the research to highlight and help us catch—and correct—failures of data and failures of analysis.

AREA addresses the critical component of timing head-on

High-stakes decisions deserve time and attention, but we’re in such a rush to reach a conclusion that we never take the time for deep reflection. We’re already over-programmed, often answering emails late at night and waking to urgent texts. We struggle with the need to react when we also need to think. Yet when it comes to our future, we deserve the time needed for thoughtful reflection. Insight doesn’t come from collecting information alone; it comes from brainwork, so AREA builds in what I call “Cheetah Pauses.” Why the cheetah? Because the cheetah’s prodigious hunting skills are not due to its speed. Rather, it’s the animal’s ability to decelerate quickly that makes it a fearsome hunter.

Cheetahs habitually run down their prey at speeds approaching 60 miles per hour, but are able to cut their speed by 9 miles per hour in a single stride, an advantage in hunting greater than being able to quickly accelerate. This allows the cheetah to make sharp turns, sideways jumps, and direction changes.

As cheetah researcher Alan Wilson explained in a 2013 New York Times article, Cheetah’s Secret Weapon: A Tight Turning Radius, “The hunt is much more about maneuvering, about acceleration, about ducking and diving to capture the prey.”

Similar to the cheetah’s hunt, the AREA Method offers both stability and maneuverability; it doesn’t consistently move forward. Instead, it benefits from calculated pauses and periods of thoughtful deceleration that will enable you to consolidate knowledge before accelerating again. The reason: A quality research and decision-making process is about depth, flexibility, and creativity.

The method’s Cheetah Pauses work as strategic stops during and after each part of your research. They enable you to chunk your learning, prevent you from going off course, and provide a clear record of your work at each stage. But most importantly, they will help you hone in on the motivation for making your high-stakes decision and identify what is most critical to you in the outcome. These are what I call “Critical Concepts.” They get at the driving purpose behind your decision.

Critical Concepts (CCs) are the one, two, or three things that really matter to you. They answer the question “What am I really solving for?” There is no single answer. Critical Concepts are going to vary from person to person. Different decision-makers will have different time horizons in which to make their decisions, different personalities, and different goals. Two people looking at the same data may have different CCs and may make entirely different decisions.

As you move through the AREA Method, the pauses will help you continually refine and re-articulate your CCs based upon what you learn and synthesize from your research. They are an integral part of the AREA process. The goal of the CCs is to ensure you are laser-focused on making a decision that uniquely addresses the essence of what you really need to resolve. Taking the time to identify what’s critical to you—your CCs—is the foundation to my analytical method.

You don’t need lots of money or resources to make a good decision, but you do need good methodology and a clear sense of what you want out of your decision. Whether you’re making a critical professional or personal decision, the AREA Method is an equitable tool that gives you a step-by-step framework that focuses your work and thinking on Critical Concepts.

AREA provides a clear, concise, and repeatable process that works as a feedback loop

Not all investigations are linear, nor should they be. At times you need to be driven back into earlier steps to do more work, collect more data, or conduct further analysis.

Still, while every hunt a cheetah undertakes is different, an experienced hunter learns from past hunts and uses these lessons to make them more effective. The same is true for making decisions about ideas, opportunities, or problems. A solid research and decision-making process should be explicit, improvable, flexible, and, above all, repeatable. The process should not start an...