eBook - ePub

7 Secrets of Persuasion

Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence Anyone

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Jim Crimmins explains what really drives human behavior. For anyone who hopes to influence what people do or what they buy, Jim's book is required reading." —Keith Reinhard, chairman emeritus of DDB Worldwide and a member of the Advertising Hall of Fame

7 Secrets of Persuasion is the first book to take the latest scientific insights about the mind and apply them to the art of persuasion. It directly translates the revolution in neuroscience that has occurred over the last 40 years into practical new techniques for effective persuasion.

Whether your goal is to persuade one person--a husband, child, or boss--or the millions who might purchase an Apple Watch or a Budweiser, 7 Secrets of Persuasion will show you how to:

7 Secrets of Persuasion is the first book to take the latest scientific insights about the mind and apply them to the art of persuasion. It directly translates the revolution in neuroscience that has occurred over the last 40 years into practical new techniques for effective persuasion.

Whether your goal is to persuade one person--a husband, child, or boss--or the millions who might purchase an Apple Watch or a Budweiser, 7 Secrets of Persuasion will show you how to:

- Unearth the motivation that actually changes a behavior like smoking, voting, or buying, even though people don't know why they do what they do.

- Tap into the mental process that gives religious symbols, political symbols, and commercial logos their power.

- Make a promise that is delayed, uncertain, and rational more compelling by making it immediate, certain, and emotional.

- Transform your candidate, service, or product into the one people want by utilizing what psychologists call the "fundamental attribution error."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 7 Secrets of Persuasion by James C. Crimmins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

GETTING TO KNOW THE LIZARD

Whether persuading your boss, your kids, or your spouse, or persuading millions to eat healthier foods, to vote for your candidate, or to choose a Galaxy phone, persuasion often fails. A better understanding of the mind improves the chance of success.

Recent discoveries in psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroscience dramatically expand what we know about how we choose and should change how we attempt to persuade. We’ve learned that consciousness is not central to most of our decisions. It feels central, but scientific evidence shows that consciousness usually takes a back seat. This turns the conventional wisdom of persuasion on its head and may explain why persuasion attempts, whether of one person or of many, often don’t work.

As a professional persuader for 27 years—mainly as Chief Strategic Officer of DDB Chicago and a Worldwide Brand Planning Director—I was in charge of analyzing what should work, what did work, and what didn’t work for such clients as Budweiser, Dell, Discover Card, and Westin. I found myself puzzled by both failures and successes, and spent a great deal of time trying to figure out what made an advertisement go one way or another. The conventional wisdom of advertising didn’t seem to apply. As I studied the latest research into our brains and our decision-making, I began to see why. I became intrigued with scientists who, for the first time, were shedding light on the dark matter of the mind. I could see why the traditional approach to advertising failed and how we had to update our ideas on persuasion.

This book takes the latest scientific insights about the mind and applies them to the art of persuasion. Until now, persuasion has been hit or miss because would-be persuaders didn’t understand how we choose. But thanks to the groundbreaking research of such scientists as Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and others beginning 40 years ago, in what has been a revolution in mind science, today we better understand how we make decisions. I translate this revolution into practical techniques for successful persuasion. These techniques will help anyone become more persuasive, whether the goal is to influence one person—a relative, friend, or colleague—or the many who might purchase an Apple Watch or a Chevy.

We have two different ways of thinking: (1) the automatic system—our nonconscious mental processes, and (2) the reflective system—our conscious mental processes. We now know the automatic system affects all our choices and is the sole influence in many. The roots of our automatic, nonconscious mental system lie in ancient brain structures we share with lizards and, indeed, all vertebrates. Although the degree of development of the nonconscious mind varies considerably across species, its basic function remains the same: to pursue pleasure and avoid pain. The automatic mental system is what Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein referred to as the lizard inside.1

Thaler, Sunstein, and I don’t mean to disparage the automatic, nonconscious mental system by calling it the lizard inside. Thanks to our automatic system we can walk, talk, understand the input of our senses, develop likes and dislikes, choose friends, and fall in love. The lizard is smart and intuitive. It’s who we are when we aren’t thinking about it. The lizard acts without conscious deliberation, instantly, effortlessly, and can’t be turned off.

The lizard looks at life differently than our conscious mental system.

• For the lizard, what comes most easily to mind seems most true. The lizard can’t tell the difference between familiarity and accuracy.

• For the lizard, people are what they do no matter why they do it. The lizard focuses on action and ignores motivation.

• Because of the lizard, persuasion should aim at the act rather than the attitude, as behavior is easier to change.

• Because of the lizard, we should never ask people why they do what they do. People don’t know why, but they think they do. You can find out what you need to know, but you won’t find out by asking.

• The lizard is partial to immediate, certain, and emotional rewards, but good-for-you choices like dieting, saving money, or stopping smoking offer the opposite. Understanding the lizard allows you to transform rewards, changing the delayed into the immediate, the uncertain into the certain, and the rational into the emotional.

The seven secrets of persuasion revealed in this book are not a collection of separate techniques that you need to choose among. You can use any one, two, or all of them whenever you attempt to persuade, whether you seek to persuade one or many, and whether the goal is important or trivial.

The secrets of persuasion succeed by dealing with the lizard.

The Lizard

You may have a spouse. You very likely have a religion. You certainly have a number of friends. How did you choose them?

Did you evaluate each person relative to others on their spouse-potential? Did you analyze all religions and choose the one you found most compelling? Do you remember considering the wide range of people you know and selecting certain individuals to be your friends?

Of course not; no one does. Even though these choices may be the most important decisions of your life, you didn’t go through any conscious process to make them. You made the choices. You just don’t know exactly how.

We don’t make choices the way we think we do. We think we consciously consider the options and we believe we know why we pick one option over the others. It doesn’t work that way. No matter how it feels, consciousness is not crucial to most of our decisions. Our conscious mind is often on the periphery of our choices.

In the words of Jonathan Miller in the New York Review of Books, “Human beings owe a surprisingly large proportion of their cognitive and behavioral capacities to the existence of an ‘automatic self’ of which they have no conscious knowledge and over which they have little voluntary control.”2

For most choices, our nonconscious, automatic mental system, the lizard inside, is in charge. To persuade the lizard, we must understand it and speak its language.

David Eagleman is a neuroscientist at Baylor College of Medicine, where he directs both the Laboratory for Perception and Action and the Initiative on Neuroscience and Law. In his book, Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, Eagleman tells us that the realization that consciousness is not central to behavior is as radical as the realization that the earth is not the center of the solar system.3 Derision, anger, and prosecution met Galileo’s announcement. The Vatican censored his works for 200 years.

To people in the 17th century, it was obvious that the earth was the center of the solar system. They could feel it in their bones when the sun passed overhead each day. It seems just as clear to us that consciousness is central to our behavior. But, in both cases, scientific evidence to the contrary is undeniable.

Sigmund Freud first brought attention to the unconscious. He understood the importance of our nonconscious processes, but he misunderstood their nature. Freud believed that the unconscious contained primitive urges for sex and aggression that are so powerful we need to keep them out of awareness. What we understand today about mental processes outside of conscious awareness is far from the roiling set of embarrassing desires that come to mind when most people think of Freud’s unconscious.

Contemporary psychologists do not want their work on non-conscious processes to share the connotations of the Freudian unconscious. They have generally avoided the term “unconscious” and referred to nonconscious processes as “implicit,” “pre-attentive,” or “subconscious.” Unfortunately, these labels suggest our nonconscious system is somehow less important than our conscious system.

Daniel Kahneman solved that problem by calling nonconscious processes, or “thinking fast,” System 1, and calling conscious processes, or “thinking slow,” System 2.4 But System 1 and System 2 make it too hard to keep track of which is conscious and which is nonconscious.

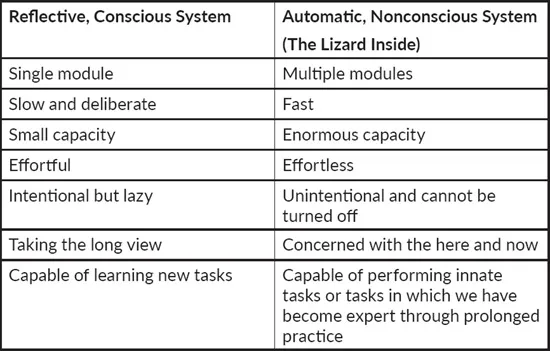

Thaler and Sunstein used labels that are both descriptive and memorable. Richard Thaler, an economist at the University of Chicago, working with Cass Sunstein, a prolific legal scholar at Harvard Law School, wrote their best-selling Nudge to show how the science of choice could be used to nudge people toward decisions that will make their lives better.5 Thaler and Sunstein describe non-conscious processes as the “automatic system” and conscious processes as the “reflective system.”

I’ll borrow from Thaler and Sunstein and refer to our nonconscious mental processes as the automatic system (that is, the lizard inside) and refer to our conscious mental processes as the reflective system. Automatic and reflective are clear and avoid suggesting that nonconscious processes are subordinate.

Both the automatic and reflective mental systems are active whenever we are awake. The lizard inside, the automatic, nonconscious mental system, usually takes the lead generating impressions, feelings, inclinations, and impulses whereas our reflective, conscious mental system goes along with the automatic system’s suggestions unless provoked.

The mental system outside of our awareness is much more influential than we realize, having a powerful influence on all our choices and judgments. Our automatic, nonconscious mental system, the lizard inside, not only influences the options we choose, but also plays a key role, often the sole role, in originating any action we take.

Our reflective, conscious system is important in some actions, especially those for which we were not well prepared by evolution like dieting, calculus, and science, or not well prepared by frequent repetition or habit like finding our way in an unfamiliar city, or following the protocol of meeting royalty.

The automatic system, the lizard inside, directs all those internal procedures that keep us alive—blood pumping, breathing, digestion. But that is just the beginning. Our automatic, nonconscious mental system enables us to understand what we see or hear turning the massive amounts of data coming in through our senses into understandable patterns. Our automatic system allows us to speak and stay upright and catch a fly ball. Because all these wondrous operations take place outside of conscious awareness, we find it hard to give credit. Eagleman compares our conscious mind to “…a tiny stowaway on a transatlantic steamship, taking credit for the journey without acknowledging the massive engineering underfoot.”6

In order to succeed at persuasion we have to deal with the lizard inside, the automatic mental system. We have to learn how the lizard works and how it can be influenced.

Psychologists, neuroscientists, and behavior economists have spelled out the differences between the reflective, conscious mental system and the automatic, nonconscious mental system. The following chart summarizes the differences.7

The reflective, conscious mental system has one module. Our conscious mental system is either on or off. We are either conscious or we are not.

The automatic, nonconscious mental system consists of multiple modules. Our automatic mental system guides many largely independent activities—digestion, circulation, breathing, depth perception, balance, language, and so on. Patients with brain damage can completely lose certain capabilities, like depth perception, whereas other capabilities, like language, function normally.

The reflective system is slow and deliberate, but the automatic system is fast. A study by psychologists at Northwestern University illustrated the speed of the automatic, nonconscious system relative to the reflective, conscious system.8

Participants were shown on a computer screen human faces expressing surprise. Unbeknownst to the participants, before they saw the surprised faces, they were shown, for 30 milliseconds, faces either with fearful expressions or happy expressions. At 30 milliseconds, or 3/100 of a second, the fearful or happy expressions were too brief for participants to be consciously aware of them.

Participants then rated the surprised faces from “extremely positive” to “extremely negative.”

Participants who unconsciously saw the initial fearful micro-expressions rated the surprised faces more negatively than participants who unconsciously saw the initial happy micro-expressions.

The automatic, nonconscious system saw the initial faces shown for 3/100 of a second, interpreted the meaning, and provided consciousness with an inclination that influenced conscious perception even though consciousness had no idea the initial pictures were shown.

When we meet new people, their faces often reveal, for an instant, their pleasure or lack of pleasure in meeting us. After that instant, which is too fast for our conscious mind to pick up, their polite smiles are in place. But our automatic system catches the instantaneous expressions and leaves us with a vaguely positive or negative feeling about the new people.

These psychologists suggest that we continually, automatically, and unconsciously scan the environment for threats. In searching for threats, speed is essential.

Imagine you are a salesperson in a Ford showroom and a man walks in the door thinking about buying a car. If you don’t genuinely like that potential buyer even before he walks in, you are already in a hole. The buyer instantly, effortlessly, and without even knowing it, senses what you think of him. What he senses will affect your entire interaction. If you want to sell more cars, work on genuinely liking people even before you meet them. Will Rogers said, “I never yet met a man that I dident like.”9 Will would have been a heck of a salesman.

I recently bought a car and didn’t analyze the experience at the time. But when my wife asked me about it, I realized that I had gotten the immediate impression that the salesman in the first dealership thought very highly of himself and a lot less highly of me. He may have been right, but he seemed to form that judgment even before he met me. It soured the interaction and I bought the car somewhere else.

The reflective, conscious mental system has limited capacity, whereas the automatic, nonconscious mental system has enormous capacity. Scientists have estimated the capacity of our mental systems. By examining our ability to distinguish sounds, smells, tastes, and stimuli to the skin, as well as the number of linguistic bits we can process when we read or listen, scientists estimate that our reflective, conscious mental system can process about 40 pieces of information a second.

They have also gotten a good idea of the bandwidth of our automatic, nonconscious mental system by counting how many nerve connections send signals to the brain and how many signals each connection sends a second. The eyes alone send 10 million pieces of information to the brain every second. The rest of our senses together—touch, sound, smell, taste—send more than one million more pieces of information every second. In other words, our nonconscious mental system processes the 11,000,000 pieces of information per second that are submitted by our senses.

The difference in the estimated capacity of the two mental systems is so large that some might doubt the accuracy of the estimates. But even if those estimates are way off, the capacity of the automatic, nonconscious system still dwarfs the c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1. Getting to Know the Lizard

- 2. Speak the Language of the Lizard: Basic Grammar

- 3. Speak the Language of the Lizard: Style

- 4. Aim at the Act, Not the Attitude

- 5. Don’t Change Desires, Fulfill Them

- 6. Never Ask, Unearth

- 7. Focus on Feeling

- 8. Create Experience With Expectation

- 9. Add a Little Art

- 10. Personal Persuasion

- Conclusion

- Chapter Notes

- Bibliography

- Index