![]()

Chapter 1

The Kazakhstan Economy: Achievements, Prospects, and Policy Challenges

Kym Anderson, Giovanni Capannelli, Edimon Ginting, Kristian Rosbach, and Kiyoshi Taniguchi

Kazakhstan is at a crossroads of geographic and economic importance. The country is located along the great silk road—an ancient transit network and the center of trade and civilization connecting Europe and Asia. Kazakhstan is the largest economy in Central Asia, endowed with extensive natural resources and reliant largely on revenues from the export of primary commodities, particularly petroleum and natural gas. The Kazakhstan government has been keen to diversify its economy, as most of its economic growth from 2000 to 2010 was based on the exploitation of its natural resources. Its oil-and-gas sector generated 21% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) at its peak in 2005 (World Bank 2017), contributing a major part of public revenues. The sustained revenue created from it enabled the country to achieve fast-paced growth, build more infrastructure, improve education and healthcare, and position itself well within the global arena. However, the recent rapid decline in global prices of fossil fuels, and the expectation that they will remain low in real terms for the foreseeable future as the world transitions to less-pollutive fuels, poses significant challenges for Kazakhstan’s economy and society.

The two dominant influences on the Kazakhstan economy over the past decade have been the commodity price boom and subsequent slump, and the economic conditions of major trading partners, especially the Russian Federation. The oil price is the major determinant, since more than 70% of export earnings have come from oil and gas in recent years. The links between Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation include (i) the historical and political relationship, (ii) Kazakhstan’s imports of Russian consumer goods, and (iii) their similar reliance on oil and gas price movements due to similar export structures. The recent fall in international oil prices, coupled with the devaluation of the Russian currency, ensured that Kazakhstan’s economy experienced a massive slowdown in its rate of growth. Under the current situation of low oil prices, the government is examining its policy options for stimulating and diversifying the economy to ensure sustainable and equitable growth (Government of Kazakhstan 2017).

In 2014, Kazakhstan signed on as a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, which came into effect in 2015. Kazakhstan also joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2015. These moves signaled that the country has an ongoing interest in promoting trade, including through regional integration. They coincided with the launching of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which offers great potential for both transit trade through Kazakhstan and more investment within the country in export-oriented production of products that could become more competitive with the lowering of trade costs associated with that transit traffic. Both prospects could contribute to economic diversification of the country and broaden its range of foreign exchange earnings.

Moving forward, Kazakhstan’s economic transformation will be more challenging than in the recent past. Commodity prices, particularly of fossil fuels, are projected to remain subdued. To weather the detrimental impacts of prolonged weak external conditions, it is imperative that the non-oil deficit be reduced, and that non-oil revenues rise to support the desired level of fiscal spending. This will require sound macro-prudential policies and other policy reforms.

With the rapid and ongoing development of global value chains (GVCs), there is less and less need for production and consumption to have to be in the same place. Kazakhstan can potentially engage its well-educated skilled labor via participation in GVCs even though the country is landlocked. For Kazakhstan to become one of the world’s high-income countries, total factor productivity (TFP) growth is the key (ADB 2017). Sustainable economic growth cannot be underpinned without enhanced productivity growth. In the case of Kazakhstan, it requires a transformation of its economy away from heavy dependence on extractive resources to earn export revenue. The government needs to improve the business environment to attract more investment from the private sector, particularly foreign direct investment (FDI) in non-extractive sectors. At the same time, it needs to avoid distorting incentives via its intervening in markets.

In this chapter we provide an overview assessment of recent growth dynamics and their impact on income inequality.

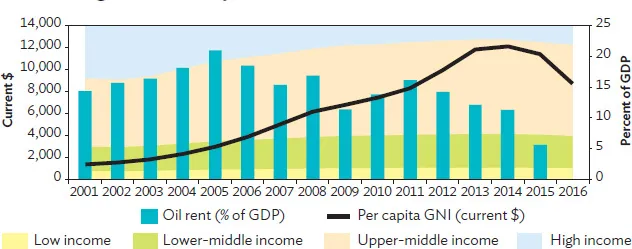

1.1. Growth, Inequality, and Environmental Dynamics

After becoming an independent country in 1991 following the dismantling of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan faced tremendous economic challenges throughout the 1990s. The country overcame many of these, reorganized its economy, and achieved strong economic growth between 2000 and 2014, when oil rents exceeded 10% of GDP, averaged 15% during 2005–2014, and peaked at 21% in 2005 (see blue bars in Figure 1.1). In 2006, Kazakhstan entered the upper-middle income group of countries and it almost broke into the high-income group in 2014 (Figure 1.1), making it an economic and political power in Central Asia. But the downturn of oil and other commodity prices from 2014 resulted in a decline in per capita income and in the share of oil and gas revenue in the country’s GDP and exports. The same occurred in many resource-rich, primary product-exporting countries, including high-income ones such as Australia (Lowe 2015).

Social development in Kazakhstan has accompanied this strong economic growth. The country has achieved most of the original and additional targets of its Millennium Development Goals, such as poverty reduction, access to primary education, promotion of gender equality and women empowerment, and improvement in children’s and maternal welfare (United Nations 2010). As of 2016, the share of the poor on the basis of the national poverty line (% of the population) decreased to 2.6% from 46.7% in 2001. The gap in income inequality also decreased, as evidenced by the decline in the Gini index from 34.8 in 2001 to 27.3 in 2017. However, the country’s Millennium Development Goal 7 target of ensuring environmental sustainability has been only partly achieved.

Kazakhstan records consistently low figures for unemployment, with levels around 5% since 2011 (5.4% in 2011 and 5% in 2016) according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). This excludes 29% of the working age population classified as economically inactive. Officially, unemployment of youth aged 15-24 is low (3.8% in 2016), but in the third quarter of 2016 the share of youth who were not in education, employment, or training (and not actively looking for a job or registered as unemployed) was much higher at 9.5%.

The labor code of Kazakhstan ensures equal work opportunity and treatment across gender. The code articulates explicitly on the protection of women from any form of discrimination. According to statistics, the female labor force participation rate in Kazakhstan is among the highest in Central Asia.

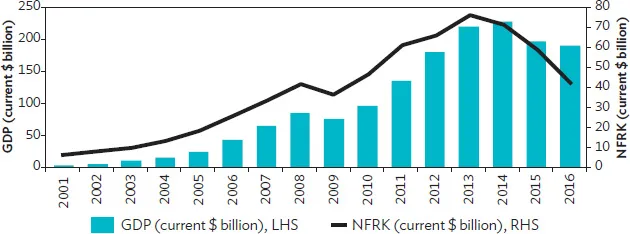

1.2. The National Wealth Fund

To manage its revenues from oil earnings effectively and prudently, the Government of Kazakhstan created the National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan (NFRK) by Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 402 on 23 August 2000 (Kemme 2012). The NFRK operates as both for stabilization and savings fund, overseen by a Management Council appointed by the President, and managed by the Treasury Department of the National Bank of Kazakhstan (NBK). Volume and uses of the Fund are determined by the President based on suggestions from the Management Council.

The NFRK was originally designed to distribute oil rents across generations. In fact, most oil-related public revenues, which represented approximately 10% of GDP in 2012–2014, are channeled to the NFRK and sterilized (OECD 2016). A series of economic shocks—the global financial crisis in 2008, the oil price drop in 2014, and the economic slowdown in major trading partners—revealed structural vulnerabilities of the economy that pose risks for the sustainability of the achieved levels of economic development and inclusion. The NFRK has been increasingly used to provide a cushion against economic shocks. The share of revenue being transferred from the NFRK to the government budget reached 40% of total government revenue in 2015, when there was a net drawdown of the NFRK (Figure 1.2). The NFRK is also used (with mixed success) to help transition to a more diversified economy, with high domestic value addition in manufacturing and services as well as less reliance on revenues from commodity exports.

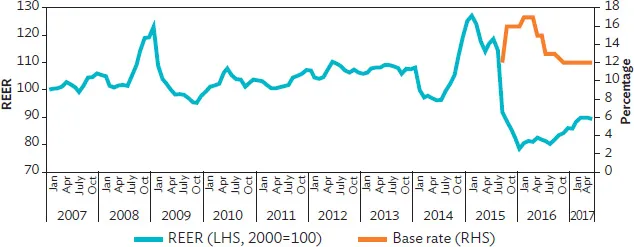

1.3. Real Exchange Rate Movements and the Inflation Target

Kazakhstan’s deteriorating external conditions from 2014 posed a threat to its pegged exchange rate (OECD 2017). The country responded to the challenges from the recent fall in oil prices and the slowdown in economic growth in the PRC, Europe, and the Russian Federation in several ways: not just exchange rate adjustment but also targeted fiscal support and enhanced monetary policy management (IMF 2017).

Moving toward a flexible exchange rate is desirable. Well-received theory indicates that, while fixed exchange rates can be effective in dealing with internal demand shocks, flexible exchange rates work best for external trade shocks (Frankel 2013). This is because flexible exchange rates can adjust to real shocks automatically in real time. Kazakhstan, like all natural resource-rich economies, has been very vulnerable to external trade shocks, especially a fall in the world oil price. This vulnerability has now been reduced by the move to a more flexible exchange rate regime.

After the global financial crisis in 2008 and its own banking crisis, Kazakhstan devalued the tenge in February 2009 by 18%, to 150 per dollar plus or minus 5 tenge (Figure 1.3). The pegged exchange rate regime (i.e., within a narrow corridor against a basket of currencies) had been supported by the positive external environment including rising export prices and solid growth in the diversity of trading partners. It led to strong inflows of foreign investment. However, the NBK devalued the tenge by 19% in February 2014 because of the effect of United States tapering on emerging markets (Horton et al. 2016). In August 2015, the NBK decided to let the tenge float as part of a shift to an inflation-targeting regime. At the same time, the NBK introduced the one-day repo rate (aka the base rate) set at 12%. The current exchange rate policy regime allows the tenge’s value to be determined by fundamentals, which are influenced mainly by the oil price and developments in major trading partners, especially the Russian Federation. This new floating exchange rate regime is expected to accommodate much better to any future external shocks than was the case under a fixed rate regime.

After the introduction of the one-day repo rate in August 2015, the real effective exchange rate decreased substantially (a real depreciation of the currency), which meant that exports became more competitive internationally and imports became more expensive in local currency terms.

Figure 1.4 shows that inflation has declined as exchange rate pressures subsided in 2017 (IMF 2...