- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How the law harms sex workers - and what they want instead

Do you have to endorse prostitution in order to support sex worker rights? Should clients be criminalized, and can the police deliver justice?

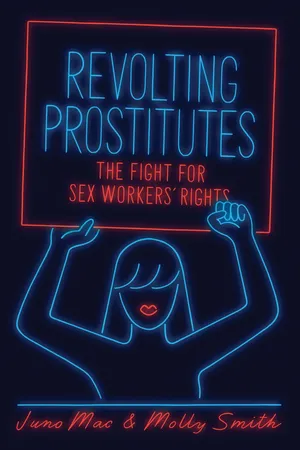

In Revolting Prostitutes, sex workers Juno Mac and Molly Smith bring a fresh perspective to questions that have long been contentious. Speaking from a growing global sex worker rights movement, and situating their argument firmly within wider questions of migration, work, feminism, and resistance to white supremacy, they make it clear that anyone committed to working towards justice and freedom should be in support of the sex worker rights movement.

Do you have to endorse prostitution in order to support sex worker rights? Should clients be criminalized, and can the police deliver justice?

In Revolting Prostitutes, sex workers Juno Mac and Molly Smith bring a fresh perspective to questions that have long been contentious. Speaking from a growing global sex worker rights movement, and situating their argument firmly within wider questions of migration, work, feminism, and resistance to white supremacy, they make it clear that anyone committed to working towards justice and freedom should be in support of the sex worker rights movement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Revolting Prostitutes by Molly Smith,Juno Mac in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sex

We are anxious about sex. For us as women, sex can be as much a site of trauma – or uneasy compromise – as a site of joy or intimacy. Feminist conversations about sex work are often seen as arguments between those who are ‘sex positive’ and those who are ‘sex negative.’ The reasons for this will be explored in this chapter. We have no interest in positioning ourselves within that terrain. Instead, we assert the right for all women to be ‘sex-ambivalent’. That said, the hatred of sex workers is rooted in very old and misogynist ideas about sex. Understanding those visceral responses of disgust is a key starting point for understanding all kinds of things about prostitution – including criminal law.

Is Sex Bad?

People are preoccupied with the sexual dimension of sex work. These anxieties manifest in ideas of bodily degradation and the threat that sex workers pose as the vectors of such degradation. The prostitute is seen as a disease-spreader, associated with putrefaction and death. We are envisioned both as removing corruption from society (a nineteenth-century French physician spoke of the ‘seminal drain’)1 and as a source of contamination, disease, and death in our own right.2 Puta, the Spanish word for prostitute, has links with the English putrid.* Another preoccupation holds that to have sex (or to have sex in the wrong ways – too much, with the wrong person, or for the wrong reason) brings about some kind of loss. Often, contradictory ideas about sex and these visceral threats or losses are intertwined in cultural depictions of the sex worker – forming a figure that Melissa Gira Grant names the ‘prostitute imaginary’.3

Sometimes the connection between these ideas is obvious. For the Victorians, the ‘loss of virginity’ risks ruin and a grim death from syphilis. The ruined woman is reconfigured as an agent of destruction, spreading disease in her wake. Sometimes the loss is a spiritual decline she precipitates in others; in 1870, for example, journalist William Acton wrote that prostitutes are ‘ministers of evil passions, [who] not only gratify desire, but also arouse it [and] suggest evil thoughts and desires which might otherwise remain undeveloped’.4 In The Whore’s Last Shift, a 1779 painting by James Gillway, the tragic figure of a heavily made-up nude woman with hair piled high stands by a broken chamber pot in a dirty room, washing her filthy – and clumsily symbolic – white dress by hand.

Attitudes towards the prostitute imaginary can be read in context with the more familiar paradox around a specific body part. Ugly, stretched, odorous, unclean, potentially infected, desirable, mysterious, tantalising – the patriarchy’s ambivalence towards vaginas is well established and has a lot in common with attitudes around sex work. On the one hand, the lure of the vagina is a threat; it’s seen as a place where a penis might risk encountering the traces of another man or a full set of gnashing teeth. At the same time, it’s viewed as an inherently submissive body part that must be ‘broken in’ to bring about sexual maturity. The idea of the vagina as fundamentally compromised or pitiful is helped along in part by a longstanding feminist perception of the penetrative sexual act as indicative of subjugation.5

The nineteenth century Contagious Diseases Act gave police the power to subject any suspected prostitute to a forced pelvic exam with a speculum – a device, still in use today, invented by a doctor who found gynaecological contact repellent, and who purchased enslaved Black women to experiment on.6 In London in 1893, Cesare Lombroso studied the bodies of women from the ‘dangerous classes’, mostly prostitutes and other working class women, and women of colour, all of whom he described as ‘primitive’. He asserted that prostitutes experienced increased pubic-hair growth, hypertrophy of the clitoris, and permanent distention of the labia and vagina, clearly believing that their unnatural deeds and their unnatural bodies were two sides of the same coin.7 To him, the social and moral degradation they represented became legible in their physical bodies.

An 1880s novel describes a sex worker as ‘a shovel full of putrid flesh’, continuing: ‘It was as if the poison she had picked up in the gases from the carcasses left by the roadside that ferment – with which she had poisoned a whole people – had risen to her face and rotted it.’8 The body of the prostitute is out to hurt innocents: she is ‘carrying contamination and foulness to every quarter’, where ‘[she] creeps … no precautions used … and poisons half the young’.9

During World War II, the disease-ridden prostitute was imagined as the enemy’s secret biological weapon. Posters depicted her as an archetypal femme fatale – with a cigarette between her red lips, a tight dress, and a wicked smile – above slogans warning that she and other ‘pickups’ were dangerous: traps, loaded guns, ‘juke joint snipers’, Axis agents, enemies of the Allied forces, and friends of Hitler.10

These questions about the duplicity of the sexualised body also come up around queer and gender non-conforming people. Trans women are often questioned about their ‘biological’ status: a demand that invariably reveals an obsessive focus on their genitals. A trans woman is constantly targeted for public harassment; at the same time, if she is ‘read’ as trans, she is seen to be as threatening as a man – accused of trespassing into bathrooms to commit sexual violence.11 Conversely, if she can pass for cisgender, she is regarded as dangerous, liable to ‘trap’ someone into having sex with her unawares.*

Gay men have also been historically perceived through this mistrustful lens. Queer theorist Leo Bersani argues that gay men provoke the same sets of fears long embodied by the prostitute: a person who could either ‘turn’ decent men immoral or destroy them. The HIV crisis brought new virulence to these homophobic fears. An HIV researcher wrote at the time of the epidemic that, ‘These people have sex twenty to thirty times a night … A man comes along and goes from anus to anus and in a single night will act as a mosquito transferring infected cells on his penis.’12 These fears about gay men as malevolent and reckless persist today. A Christian hate group that advocates against ‘sodomist and homosexualist propaganda’ was invited to the UN in 2017, and a feminist writer recently described a male HIV-positive sex worker as ‘spreading AIDS.’13

To be associated with prostitution signifies moral loss. In 1910, US district attorney Edwin Sim wrote that ‘the characteristic which distinguishes the white slave from immorality … is that the women who are victims of the traffic are forced unwillingly to live an immoral life’.14 This belief – that to be a sex worker is to live an ‘immoral life’ – has persisted. Mark Lagon, who led the US State Department’s anti-prostitution work during the George W. Bush era (and went on to run the biggest anti-trafficking organisation in the US), wrote in 2009 that women who sell sex lead ‘nasty, immoral lives’ for which they should only not be held ‘culpable’ because ‘they may not have a choice’.15

In the 2000s, the blog Diary of a London Call Girl, written by escort and anonymous blogger ‘Belle de Jour’, was a smash hit, leading to books and a TV show. After its author was named in 2009 as the research scientist Brooke Magnanti, journalists, like Lombroso before them, attempted to read her supposed moral loss in her physical body: ‘I scrutinize [Magnanti’s] face without quite knowing what I’m looking for … dead eyes, maybe … or something a bit grim and hard around the mouth.’16 Sex work, categorised as the wrong kind of sex, is seen as taking something from you – the life in your eyes. In her imagined loss, Magnanti is transformed in the journalist’s eyes into a threat, a hardened woman.

This supposed sexual excess, and the loss that accompanies it, delineates the prostitute as ‘other’. The ‘good’ woman, on the other hand, is defined by her whiteness, her class, and her ‘appropriate’ sexual modesty, whether maidenly or maternal. Campaigns for women’s suffrage in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries drew on the connection between women’s bodies and honour and the honour and body politic of the nation. These campaigns were intimately linked with efforts to tackle prostitution, with British suffragists engaging in anti-prostitution work ‘on behalf’ of women in colonised India to make the case that British women’s enfranchisement would ‘purify the imperial nation-state’.17

This sense that people (particularly women) are changed and degraded through sex crops up in contemporary feminist thought about prostitution, too. Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, who runs a diversion programme for arrested sex workers in Arizona, claims that ‘once you’ve prostituted, you can never not have prostituted … having that many body parts in your body parts, having that many body fluids near you, and doing things that are freaky and weird really messes up your ideas of what a relationship looks like, and intimacy’.18 Sex workers who go through that programme have to abstain not only from selling sex but also from sex with a partner.19

Even more punitive responses were common in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and even twentieth centuries. Orders of nuns across the world ran workhouses and laundries for ‘fallen women’ – prostitutes, unmarried mothers, and other women whose sexualities made their communities uneasy.20 Conditions in these ‘Magdalene laundries’ were primitive at best and often brutal; even in the twentieth century, women could be confined within them for their whole lives, imprisoned without trial for the ‘moral crime’ of sex outside of marriage. Many women and their children died through neglect or overwork and were buried in unmarked graves. In Tuam, Ireland, 796 dead children were secretly buried in a septic tank between 1925 and 1961.21 The last Magdalene laundry in Ireland closed only in 1996.

The Irish nuns who ran the Magdalene laundries did not disappear.22 Instead, they set up an anti-prostitution organisation, Ruhama, which has become a major force in campaigning to criminalise sex work in Ireland, and now couches its work in feminist language.23 The Good Shepherd Sisters and the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity continue to make money from the real estate where the Magdalene laundries stood, while largely stonewalling survivors’ efforts to document or account for the abuses that took place there – and refusing to contribute to the compensation scheme for survivors.24 There is a direct line between these religious orders and the supposedly feminist prostitution policy implemented in Ireland in 2016 (see chapter 7).25

Tropes about the prostitute body as a carrier of sexually transmitted destruction recur in ostensibly progressive spaces, as when a ‘feminist’ anti-prostitution organisation reuses World War II–era public-health posters, or when a prominent anti-prostitution activist tells sex workers’ rights advocates that they could ‘rot in HIV-infected pits’.26 Sex workers observe such conversations to be laden with misogynist contempt, a ritual of political humiliation where our bodies are laid bare for comment. When we defend ourselves, our resistance outrages non-prostitute feminists, who seize on our obstinacy as proof that we love the sex industry and we love selling sex to men, that we’re out to corrupt, and that we hate other women.

Witness, for example, a commenter on Mumsnet, the UK’s most popular parenting forum, addressing a fellow community member with:

You whores pander to men, you undermine women, you steal our husbands, you spread disease, you are a constant threat to society and morals. How can women ever be judged on their intellect when sluts make money selling their bodies? … What you do is disgusting, letting men cum on your face? Vile and evil.27

Norwegian academics Cecilie Høigård and Liv Finstad write that the sex worker’s vagina is ‘a garbage can for hordes of anonymous men’s ejaculations’.28 We once witnessed a sex worker in an online feminist discussion being asked:

What is the condition of your rectum and the fibrous wall between your rectum and your vagina? Any issues of prolapse? Incontinence? Lack of control? You may discover that things start falling down/out when you’re a little older. Are you able to achieve orgasm? Do you have nightmares?29

Such interrogation and commentary feels far from sisterly. It doesn’t comfort or uplift sex workers to know that our being likened to toilets, loaves of bread, meat, dogs or robots is all part of a project apparently more important than our dignity.30 Feminist women describe us as ‘things’ for which one can purchase a ‘single-use license to penetrate’.31 They gleefully reference the ‘jizz’ we’ve presumably encountered and our ‘orifices’ and tell us to stick to ‘sucking and fucking’ and leave feminist...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Sex

- 2. Work

- 3. Borders

- 4. A Victorian Hangover: Great Britain

- 5. Prison Nation: The United States, South Africa, and Kenya

- 6. The People’s Home: Sweden, Norway, Ireland, and Canada

- 7. Charmed Circle: Germany, Netherlands, and Nevada

- 8. No Silver Bullet: Aotearoa (New Zealand) and New South Wales

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index