1 THE PROBLEM OF THE DEAD

In the spring of 1780 the scent of death crept into the basements of central Paris. More precisely, a row of buildings on rue de la Lingerie began to exude the distinctive and unwelcome smell of decomposing human remains. The street in question formed the western border of the city’s oldest and largest burial space, the Cemetery of the Innocents, which had been in operation for more than five hundred years. On May 30 a resident of one of the afflicted houses, Monsieur Gravelot, lodged an official complaint with the state about the cadaverous odor, which he suspected to be the cause of his wife’s recent illness. In response, the state dispatched Antoine-Alexis Cadet de Vaux, the city’s recently appointed salubrity inspector, to investigate. In his report to the Royal Academy of Sciences later that year, Cadet de Vaux confirmed Gravelot’s fears: poisonous gases had fully breached the barrier dividing Paris’s living from its dead. In at least three houses along rue de la Lingerie, cemetery vapors had seeped into sub-basements and gradually made their way up to the ground floor. To underscore the urgency of the situation, Cadet de Vaux listed the various ailments that inhabitants of the quarter had been suffering as a consequence of their exposure, including respiratory ailments, delirium, “liver obstructions,” and violent fits of vomiting. Although Cadet de Vaux embarked on a vigorous process to “demephitize” (déméphitiser) the basements, he remained convinced that the fix was temporary; the basements needed to be sealed off and the cemetery closed down.1 The prerevolutionary state acted quickly and the centuries-old cemetery officially closed by the end of 1780, but Paris’s burial problems were only just beginning.

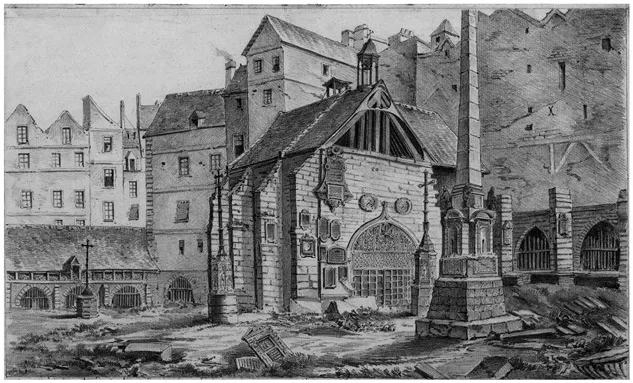

Figure 1.1. Claude-Louis Bernier, “The Cemetery of the Innocents along rue de la Lingerie in February 1786.” Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

When the Old Regime finally died after a long illness in the summer of 1789, it bequeathed a host of problems to its revolutionary successors. The most well known of these were the crippling fiscal and political crises that brought a centuries-old monarchy crashing down, but as the rue de la Lingerie incident illustrates French Revolutionaries also found themselves faced with a mounting burial crisis characterized by a shortage of spaces to safely and securely contain the dead. This problem afflicted the entire nation but it took on its most acute form in Paris, where a new Enlightenment attitude about the place of the dead in the city had the most influence.2 For centuries Parisians had been burying their dead in graveyards located throughout the city, most of which were adjacent to parish churches. By the second half of the eighteenth century, the state, armed with scientific studies and expert testimony, like Cadet de Vaux’s, decreed that this practice was dangerous to public health and contrary to reason. In practice, this meant that Paris’s oldest and most problematic cemeteries were condemned, emptied out, and razed to the ground in the years before the Revolution. Although architects and urban planners proposed a range of new and improved urban burial spaces, reform had barely advanced out of the planning stage by the summer of 1789, when the Estates General met and irreversibly changed the course of history. Thus, in addition to higher-order projects, such as drafting a constitution and rethinking the tax system, early French Revolutionaries had to resolve the dirty business of where and how to bury their dead in the capital of their new nation.

Unsurprisingly, these revolutionaries were not content to simply continue the work of the Old Regime. As they sought to address their city’s burial problem, Parisians during the Revolution began to rethink the relationship between the living and dead and explore the possibilities of a new burial culture that would be inseparable from the social and cultural reinvention of the era. In doing so, they dramatically changed the place of the dead in the capital. This process kept pace with the development of the Revolution: conversations about burial reform began in 1789 and accelerated at crucial moments when the dead caused problems and demanded attention, but it was not truly until the Revolution’s most radical years, 1792–94, that a new approach to burial reform began to take shape, characterized by inventive new types of republican burial spaces. However, this revolutionary intervention also introduced a whole new set of problems that would spill over into the nineteenth century. In addition to the logistical issues inherited from the Old Regime, such as the location and layout of new cemeteries, revolutionaries added conceptual concerns, including the role of religion, the tension between equality and hierarchy, and the place of the past in Paris’s new spaces for the dead.

Historians have generally glossed over the role that cemetery and burial reform played in the republican cultural project. This is probably because none of the planned or proposed revolutionary spaces for the dead were actually built, with the very notable exception of the Panthéon, which has certainly received its share of attention and analysis.3 Scholars interested in the place of the dead during this time have tended to focus on elaborate funeral festivals for exceptional revolutionaries and the ongoing spectacle of public violence.4 When addressing ordinary cemeteries during the Revolution, their discussion is usually limited to passing comments about de-Christianization and notorious atheist cemetery signage announcing death to be “the eternal sleep.” However, the debate about cemetery reform that began at the end of the Old Regime persisted throughout the Revolution, shifting and transforming with the radicalization of political culture. The Panthéon, republican funerals, and de-Christianization all contributed to this conversation, but they did not make up the whole story. Focusing only on accomplished projects elides other powerful ideas that were taking root during the Revolution about the role that the cemetery could play in the city, including a manifestation of social equality, a temporal link between the past and the present, and a site that powerfully bound citizens to each other and to their patrie.

Public Health and Cemeteries in the Old Regime

Prior to the 1780s, most Parisians buried their dead in the city, usually in a mass grave adjacent to their parish church. Although this kind of urban interment had been prohibited during the early Christian era for reasons of salubrity, by the ninth century the church began making exceptions for bishops, abbots, and priests who wished to be buried on church grounds. This paved the way for civilian church burial, which expanded during the medieval and early modern period, so that by the eighteenth century virtually all Parisians were buried in one of the city’s thirty-two churchyard burial spaces.5 However, the largest and oldest of the city’s burial sites, the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents, followed a slightly different model. Although it was owned by a religious community, Innocents was less of a church graveyard than a public and civic cemetery, because so many of the capital’s neighborhoods and institutions had the right to bury their dead in it, including eighteen parishes, two hospitals, and the city morgue. Innocents was also notable for its size and age: locals had been burying their dead in the area since antiquity, but during the reign of Philippe II (r. 1180–1223) the burial site was expanded to occupy a huge swath of walled-in urban space on the city’s right bank, adjacent to the les Halles marketplace. By the middle of the eighteenth century, one-tenth of the city’s dead (approximately eighteen hundred people) found their way into Innocents each year.6 Perhaps owing to its size and age, Innocents had long been associated with the city as a whole, as opposed to a particular neighborhood, parish, or population group, as smaller parish graveyards were. Indeed, throughout the early modern period, and especially during moments of strife, such as the wars of religion, city dwellers widely regarded Innocents as a powerful symbol of Parisian (Catholic) identity.7

Yet in the decades before the French Revolution, a new narrative began to supplant the earlier mythology of Innocents and urban burial in general. While burial on church property had long been standard, during the eighteenth century, a powerful scientific critique of this practice gained traction in educated circles. For centuries, physicians and natural philosophers had cautioned against the menace of bodily decay in the capital, citing miasmic theory. Eighteenth-century medical experts added legitimacy to this long-held concern with evidence culled from experimentation.8 This began in 1737 when the Parlement of Paris sponsored a medical inquiry to explore the relationship between cemeteries and public health. Two doctors from the Hôtel-Dieu hospital and one local apothecary over-saw the study. The resulting report was neither published nor widely circulated, and it focused less on the need to eliminate urban burial, than on recommendations on how to improve the salubrity of the cemetery, including a soil transplant from a much newer nearby cemetery.9 Three decades later, public complaints about Parisian cemeteries continued to accumulate, triggering a new report in 1763 about the sorry state of cemeteries in the capital. This detailed report on the status of each of the city’s cemeteries described mass graves that stayed open for months at a time, graveyards that contained so many corpses that the level of the soil was above that of the surrounding houses, and bones stacked above the rafters in churches whose charnel houses were full. The report also vividly noted that “the burials that take place in Paris are thickening the air” and surmised that “the cadavers buried beneath our feet” were the source of “otherwise mysterious illnesses” affecting city dwellers.10

In response to these widespread fears, the Parlement of Paris issued an ordinance in 1765 that condemned church burial for almost everyone and strongly suggested that all burials after January first of the new year take place in large cemeteries that would eventually be built outside of the city walls.11 This measure pleased educated reformers but met with hostility throughout the country, especially in ecclesiastical circles. The curates of Paris, in particular, produced a long and detailed refutation of the decree, arguing that “the people” would suffer if traditional churchyard cemeteries were shut down, because “the very poorest do their best to have the bodies of their loved ones taken from [the hospital] Hôtel-Dieu to [the Cemetery of the] Innocents.”12 While the curates’ objections may have been motivated by economic as much as altruistic concerns (since they would have been the ones to foot the bill for these new cemeteries), they did raise an important point when they invoked popular attachment to the city’s ancient burial grounds.13 While many Parisians, particularly among the educated elite, had come to interpret and condemn urban cemeteries as dangerous, the attitudes of the working poor toward their cemeteries were less clearly defined. As one Parisian journalist noted at the time, many Parisians had a natural and sentimental attachment to the place where their parents were buried.14 The general outcry against the 1765 ordinance proved fatal, and none of the laws were enforced.

It took the calamity at the rue de la Lingerie in 1780 to finally bring about real and lasting change. In his report before the Royal Academy of Sciences, Antoine Alexandre Cadet de Vaux explained that the air in Innocents was as infected and insalubrious as in the city’s most notorious hospitals. However, at the end of this otherwise scathing report, Cadet de Vaux imagined a better Paris, one in which everyone breathed cleaner air, where future generations would be spared the effects of “cadaverous exhalations,” and where the dead would “finally stop troubling the living.”15 Louis XVI’s government responded with a definitive decree that immediately ordered Innocents—and eventually all urban cemeteries—permanently closed. As a writer for the Journal de Paris noted later that year, only the ignorant or those acting in bad faith could possibly refute the danger that the dead posed to the living.16

For five years, Innocents sat quiet and unused until mass exhumations of the cemetery began in December 1785. It took six months of constant work to fully excavate the cemetery and remove more than twenty thousand cadavers. In Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s opinion, the excavation process was ominous, fascinating, and long overdue.17 He described a nocturnal scene in which city workers appeared as ghostly shadows, systematically dismantling funerary structures and pulling human remains out of mass graves and where the local residents of the area “woke up and rose from their beds, some came to their windows, half-dressed; others came down into the street.” The whole neighborhood, he explained, rushed to witness the historic event, with youth and beauty standing in stark contrast with “this debris of the dead!”18 Similarly, the report of the Royal Medical Society described the excavation as an “important and lugubrious” process.19 Although authors of the report noted the historic and religious significance of the Cemetery of the Innocents, they spent most of the report detailing the various states of decomposition and mummification that they observed among the disinterred cadavers.20 Both of these accounts demonstrate how significantly the imagined place of the cemetery had changed over the course of the eighteenth century. Far from being a powerful site of religious and urban identity, the historic burial ground was reduced to a morbid curiosity, albeit one rich with scientific knowledge.

Resolving the crisis at the Cemetery of the Innocents was not the end of Paris’s cemetery problems. Although Innocents was certainly the most notorious of the city’s “infected” cemeteries, it was not the only one, and increasingly throughout the 1780s residents of various neighborhoods in Paris petitioned the state to take similarly dramatic action toward their (much maligned) parish graveyards. For example, the inhabitants of St. Eustache parish in Montmartre lodged several detailed complaints in August and September 1786 to Guillaume-François-Louis Joly de Fleury, the Procurator General of Paris in which they vividly described their parish cemetery “vomiting forth an unbearable stench” that caused great suffering throughout the neighborhood.21 Adding insult to injury, the petitioners noted that when the Cemetery of the Innocents was emptied out in January 1786, the convoys of human remains traipsed directly through their neighborhood for two nights in a row, trailing “infected air” and leaving bits and pieces of human remains in their wake. By the summer, entire families were forced to relocate to avoid the quarter’s dangerous air, no one wanted to visit the area, and cadaverous exhalations regularly drove workers to abandon their projects midstream. The danger of a medical epidemic, they explained, was imminent. More than thirty inhabitants signed the longest and most detailed petition against the Saint-Eustache Cemetery.22 These particular complaints were initially dismissed by the state as the self-interested machinations of a neighborhood rabble-rouser, but in 1787 Saint-Eustache became the second Parisian cemetery, after Innocents, to be closed down and emptied out.

By the summer of 1789, when the Estates General met and unexpectedly transformed Paris into a revolutionary city, only a third additional parish cemetery had been condemned and emptied of its contents (Saint-Étienne-des-Grès). Yet reform was certainly underway and inv...