![]()

The road to hell is paved with adverbs.

—STEPHEN KING

In literary lore, one of the best stories of all time is a mere six words. “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” It’s the ultimate example of less is more, and you’ll often find it attributed to Ernest Hemingway.

It’s unclear whether it was in fact Hemingway who penned these words—the story of its creation did not appear until 1991—but it’s natural that writers and readers would want to attribute the story to the Nobel winner. He’s known for his economical prose, and the shortest-of-short stories is, at the very least, emblematic of his style.

Hemingway’s simple style was an intentional choice. He once wrote in a letter to his editor, “It wasn’t by accident that the Gettysburg address was so short. The laws of prose writing are as immutable as those of flight, of mathematics, of physics.” He believed that writing should be cut down to the bare essentials and that extra words end up hurting the final product.

Ernest Hemingway is far from alone in this belief. The same idea is raised in high-school classrooms and writing guides of every variety. And if there’s one part of speech that’s the worst offender of all, as anyone who’s ever had an exacting English teacher will know, it’s the adverb.

After listening to enough experts and admirers, it’s easy to come away with the impression that Hemingway is the paragon of concision. But is this because he succeeded where others were tempted by extraneous language, or is he coasting on reputation alone? Where does Hemingway rank, for instance, in his use of the dreaded adverb?

I wanted to find out if he lived up to the hype. And if not, who does use the fewest adverbs? Which author uses them the most? Moreover, when we look at the big picture, can we find out whether great writing does indeed hew to those efficient “laws of prose writing”? Do the best books use fewer adverbs?

* * *

I looked around and found that no one had ever attempted to determine the numbers behind these questions. So I sought to find some answers—and I started by analyzing the almost one million words in Hemingway’s ten published novels.

If Hemingway believes that the “laws of prose writing are as immutable as those of flight, of mathematics, of physics,” then I’d like to think he’d find this mathematical analysis equal parts illuminating and outlandish.

It’s outlandish at first glance because of the way we study writing. Many of us have spent days in middle school, high school, and college English classrooms dissecting a single striking excerpt from a Hemingway novel. If you want to study a great author’s writing, their most remembered passages are often the best place to start. Looking at a spreadsheet of adverb frequencies, on the other hand, won’t teach you much in the way of writing a novel like Hemingway.

But from a statistician’s point of view, it’s just as outlandish to focus on a small sample and never look at the whole picture. When you study the population of the United States, you wouldn’t look at just the population of a small town in New Hampshire for an understanding of the entire country, no matter how emblematic of the American spirit it may seem. If you want to know how Hemingway writes, you also need to understand the words he chooses that have not been put under the microscope. By looking at adverb rates throughout all his books, we can get a better sense of how he used language.

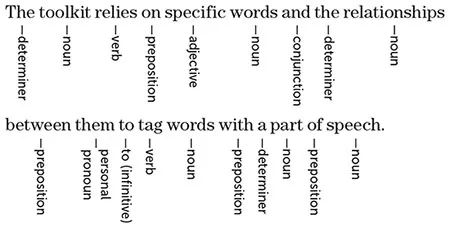

So instead of digging through snippets of Hemingway’s text and debating specific spots where he chose to use or shirk adverbs, I used a set of functions called Natural Language Toolkit to count the number of adverbs in all of his novels. The toolkit relies on specific words and the relationships between them to tag words with a part of speech. For example, here’s how it processes the previous sentence:

It’s not 100 % perfect—so all the numbers below should be seen with that wrinkle in mind—but it’s been trained on millions of human-analyzed texts and fares as well as any person could be expected to do. It’s considered the gold standard in sussing out if a word is an adjective, adverb, personal pronoun, or any other part of speech.

So what do we find when we apply the toolkit to Hemingway’s complete works?

In all of Hemingway’s novels, he wrote just over 865,000 words and used 50,200 adverbs, putting his adverb use at about 5.8 % of all words. On average, for every 17 words Hemingway wrote, one of them was an adverb.

This number without context has no meaning. Is 5.8 % a lot or a little? Stephen King, an outspoken critic of adverbs, has a usage rate of 5.5 %.

It turns out that by this standard King and Hemingway are not leaps and bounds ahead of other writers. Looking at a handful of contemporary authors who one might assume (based on stereotype alone) would use an abundance of adverbs, we see that King and Hemingway are not anomalous. E L James, author of the erotica novel Fifty Shades of Grey, used adverbs at a rate of 4.8 %. Stephenie Meyer, whom King has called “not very good,” used adverbs at a rate of 5.7 % in her Twilight books, putting her right between the horror master and the legendary Hemingway.

Expanding our search, Hemingway used more adverbs than authors John Steinbeck and Kurt Vonnegut. He used more adverbs than children’s authors Roald Dahl and R.L. Stine. And, yes, the master of simple prose used more adverbs than Stephenie Meyer and E L James.

All the sentences above are true—but they also need a giant asterisk next to them and a full explanation. Because the answer is not as simple as the numbers above first suggest.

Those tallies are counts of total adverb usage. An adverb is any word that modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb—and no adverbs were excluded or excused. But when Stephen King says, “The adverb is not your friend,” he’s not talking about any word that modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb. In the sentence “The adverb is not your friend,” the word not is an adverb. But not is not King’s issue. Nobody reads “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” and thinks never is an adverb that should have been nixed.

When King rails against adverbs in his book On Writing, he describes them as “the ones that usually end in -ly.” From a statistical standpoint his “usually” isn’t quite true (depending on the author, around 10 to 30 % of all adverbs are ones that end in -ly) but it is true that the adverbs ending in -ly are the ones that tend to stick out.

Chuck Palahniuk, best known as the author of Fight Club, has written against -ly adverbs as well. When discussing the importance of minimalism in his book Stranger than Fiction, Palahniuk writes, “No silly adverbs like ‘sleepily,’ ‘irritably,’ ‘sadly,’ please.” His general argument is that writing should allow us to know when a character is sleepy, or irritable or sad, by using a broader set of clues rather than a single word. Using -ly adverbs goes too far, telling the reader what they should think instead of setting up the scene so that the meaning becomes clear in context.

By narrowing our search to just -ly adverbs, we can cut to the heart of the debate. And when we do, the picture flips. For every 10,000 words E L James writes, 155 are -ly adverbs. For Meyer the count is 134, while King averages 105. And Hemingway, living up to his reputation, comes in at a scant 80.

Below, for the sake of comparison, is a breakdown of adverb use among 15 different authors.

Looking at this strict definition of the “bad” kind of adverb, Hemingway indeed comes out as one of the greats. As we continue to explore in this chapter, whenever I use the term adverb, I will be referring to this “bad” sort—the -ly adverb.

Was Hemingway Right?

The list on the previous page includes a variety of writers, from Nobel Prize winners to viral bestsellers. Hemingway may emerge as a titan of unadorned prose, just as the common perception of him would suggest. But any broader pattern is not so clear. E L James lands at the top of the scale, but greats like Melville and Austen also clock in toward the higher end. By adding more data points, would we be able to pinpoint a reliable pattern in adverb usage?

I wanted to find out whether an author’s adverb rate reflects anything more than just personal style or preference. I was curious: Could Hemingway have been right about the “laws of prose”? Is there any meaningful relationship between the quality of a book and how often it uses adverbs?

To start answering these questions, it’s important to note that just as different authors vary in their use of adverbs, so do different books by the same author. The rate of these -ly adverbs is rare—under 2 %—even for authors who use them more than other scribes. And there is often great variation from book to book within an author’s career.

For instance, looking at Hemingway’s novels, we see a wide range. Several of his books have adverb rates much lower than most au...