eBook - ePub

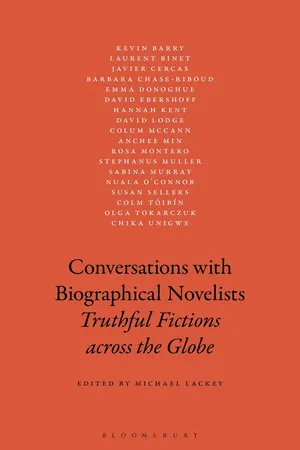

Conversations with Biographical Novelists

Truthful Fictions across the Globe

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How does a writer approach a novel about a real person?

In this new collection of interviews, authors such as Emma Donoghue, David Ebershoff, David Lodge, Colum McCann, Colm Tóibín, and Olga Tokarczuk sit down with literary scholars to discuss the relationship of history, truth, and fiction. Taken together, these conversations clarify how the biographical novel encourages cross-cultural dialogue, promotes new ways of thinking about history, politics, and social justice, and allows us to journey into the interior world of influential and remarkable people.

In this new collection of interviews, authors such as Emma Donoghue, David Ebershoff, David Lodge, Colum McCann, Colm Tóibín, and Olga Tokarczuk sit down with literary scholars to discuss the relationship of history, truth, and fiction. Taken together, these conversations clarify how the biographical novel encourages cross-cultural dialogue, promotes new ways of thinking about history, politics, and social justice, and allows us to journey into the interior world of influential and remarkable people.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversations with Biographical Novelists by Michael Lackey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism for Comparative Literature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Positive Contamination in the Biographical Novel

Kevin Barry, interviewed by Stuart Kane

Kane: Let me begin by telling you about this project. The objective is to try and define the nature of the biographical novel. It is also to clarify why this genre of fiction has become so popular in recent years. May I ask why you chose to write about John Lennon specifically?

Barry: Place is always the first thing when it comes to my writing. I’d moved to County Sligo about ten years ago, and in the early summer I’d been going out on my bike a lot around Clew Bay in County Mayo. And here we’re going to go straight into fairly esoteric country. I often think that as writers, artists, or musicians, whatever our form is, what we’re doing is trying to tune into the energies and reverberations that linger in places. I believe that human feeling escapes from humans and settles into our places. And every time I went cycling around Clew Bay I was getting this haunted feeling from the place. I was thinking a lot, whenever I was cycling around the place, about what Saul Bellow used to call “my significant dead,” or my family dead, or close friends I had lost. So there was the atmosphere of this austerely beautiful landscape mixed with this haunted feeling, and I knew that this was the atmosphere for a novel.

I had this before John Lennon came into it at all. But a little pop cultural factoid I had about Clew Bay was that John Lennon used to own an island out there. It was a familiar enough story in Ireland in the 1970s and 1980s but was long since forgotten. But I started to research it a little, or research might be a grand term for it really—I started to google a bit and found out the basics of this little story about John Lennon buying Dorinish Island in 1968. And the story lodged in my brain and just buzzed away horribly, like a bluebottle or wasp. I tried in various ways to get it out of my head. I wrote a little essay for the radio about it, for RTE. But it kept coming back, and I referred to it in a short story called “Dark Lies the Island.” John’s island is just mentioned in passing in the story and also there’s a reference to a Beatles’ track, “For No One.” I thought this would surely take care of this particular trapped wasp in my brain, but it kept coming back, again and again, along with the haunted feeling whenever I went around Clew Bay on my bike. And I remember sitting up suddenly one day, just a couple of months before City of Bohane came out in 2011. I suppose, subconsciously, I was shopping around in my brain for another novel to write. So with a start, I realized that I was going to write a novel about John Lennon.

In late 2011 I started, and it was weird. In the first few weeks, I was in this mood of glee; I thought it was a fantastic idea for a novel. Then after that first few weeks, I was in a flap and I realized how difficult it would be to get away with it.

Kane: Yes, it must have been quite a challenge to take on a character of John Lennon’s magnitude. I recently read an interview where you said that you listened to the audio of John Lennon’s voice from the 1970s to get into a rhythm for writing it. How specifically did you approach the writing of his voice?

Barry: I realized that a lot of readers were going to have an expectation, before they even got to page one, of what the character should sound like. So a lot of the first year was spent looking at YouTube, especially long interviews on the Dick Cavett Show from the 1970s, where a lot of the time Lennon is just ranting off about his visa difficulties. I transcribed sentences from his speech, directly, just to get a feel for it. And he’s especially difficult to get on the page because his tone is very capricious. He can go from being really quite charming, fluffy, and light, to being quite dark and paranoid, and all this inside the beat of a sentence. After about a year or so, the voice, just in places, was starting to sound like I might get away with it. For a long time, the story was written in the first person: I am John, but it was just too risky, even for a chancer as brazen as I am. When I moved it to the third person, it felt like the character was motoring. Then the character of Cornelius turned up, initially as a minor figure, but he began to elbow his way into the picture more and more. And it was when I made Lennon part of a double act again, with Cornelius, I think that’s when things really started to stand up on the desk for me. I could hear John Lennon’s voice very well in relief against Cornelius’s West of Ireland voice, this strange mixture of innocence and knowingness, or whatever it is he’s got going on. I could do Cornelius’s voice at will because I know many Cornelius O’Gradys. Once I got him talking, it was quite easy to have John chipping in.

So after about a year and a half, I knew that I had something, but actually that felt like a dangerous moment for the project—I knew at that point I could do a kind of standard, almost biopic version. I had a character on my desk who sounded like John Lennon, and I could now do a sort of classic buddy movie with fucking you know, character development and lovely neat arcs, but I thought this would be untrue to the spirit of the subject. I had to do something that was a bit looser, wilder, and dottier really. I do think that if you can get the voice right, you can get almost everything else following on from that. If you can get their voice, you can get their soul.

Interestingly, one of the things that gave me the confidence to attempt such an outlandish project as this was the fact that I had spent more than two years living in Liverpool in the mid-noughties. With the Liverpudlian accent, there’s kind of an easy way in for an Irish writer, because the two accents are very closely related. I was also very interested in looking at what happens when Irish sentimentality, and pathos, and singing-in-pubs, all that kind of business, what happens when that migrates to the cold cities of the North of England. What do you get when those two worlds collide? And what you get is The Beatles, coming out of that whole music-hall world.

Kane: I understand that you were very selective in your research of John Lennon, but may I ask why?

Barry: I was very wary that I had to limit my research because if you open the closet on a figure of John Lennon’s standing, the whole world will fall out on top of you and smother the project. It actually became quite a superstitious thing for me not to read anything, or look at anything on TV, or film, because it would just spoil my version of him. I did listen to the music. I listened to the White Album a lot and the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

Kane: What do you perceive as the purpose of the biographical novel?

Barry: I think with a question like that it would have to be done on a case-by-case basis. With Beatlebone, I wanted the experience of reading the novel to feel like you were being lowered down into a deep fat fryer! I wanted the reader to be lowered down into this bubbling cauldron, which is this great artist’s brain at the time of creative strife.

This is where I allowed a little bit of the real -life biography to come in because we do know that around 1978, he was creatively blocked; he wasn’t getting the songs as he had done before. The sense that you get from reading biographical stuff about John Lennon, from that time, is that he thought that the problem was that he was too happy. A lot of the issues in his life had been sorted out: his marriage was back on track, his visa difficulties had ended, he had a new baby. He was in this kind of house-husband phase but, of course, he had no songs. So then it was nice to say, well okay, I can now send him to the West of Ireland, so that he can get into trouble and try and make some work out of that. I wanted this to be a very intense experience for the reader.

I thought Lennon was obviously a very interesting character in terms of pop culture history. There are figures that come along who seem to be hinge figures, or cusp figures, who introduce something new in terms of their persona and in terms of how they carry themselves. I was really interested in how his take on masculinity seemed ahead of its time. He wasn’t the world’s most masculine rock star; he was very much in touch with his feminine side, so he seemed to be a figure ahead of his time.

Kane: What can you as a novelist give readers of John Lennon that they couldn’t get in a traditional biography? What kind of human interior does the author of biographical fiction give readers?

Barry: The traditional biography is hemmed in by the facts. I’m a reader of biographies, I love them, but where they can’t really go is inside. There is a place where only fiction can go and it’s into the nerve endings of a character, into a sense of them as pure consciousness. I think fiction is the only thing that can get you there. I think as well that you can go into narrower places than a traditional biography. The truth of the biography is the broad sweep of the life and the big events, but with fiction, you can go into the tiny moments. But then in a loose biographical fiction, such as this one, where I am making an awful lot of stuff up out of thin air, you have to imagine from nothing what it would be like for John Lennon to be eating some black pudding with a farmer in 1978. When I am writing a scene like that, all I’m thinking is if it’s true to the character at some kind of spiritual level: is this how he would react?

The only thing that my two novels have in common is that they are about being unable to escape from the shadows of the past and characters not being able to step forward because they’re constantly being dragged back. And how we have to develop some momentum in life, which is what he’s trying to do. Biographical fiction can go into the minutiae, and you can bring the character down into very small moments that hopefully can open out, and illuminate in some way their personality.

Kane: Jay Parini (critic, biographer, fictional novelist) states, “When possible, a writer of fiction should behave like a professional historian, seeking the facts where possible.” Would you agree with Parini’s statement, or do you think this is not the remit of a writer of fiction?

Barry: I think that is a perfectly legitimate remit for some writers and there is nothing in that statement that would suggest you can’t write a terrific novel in that way. Pragmatically, my difficulty with such an approach is that I am not a researcher; I skimp on the research, always, no matter what the project is, because for me research always equates to procrastination. If I’m doing research, it means I don’t want to write. So I tend to make it all happen on the desk and invent it out of the ether. What I tend to do with research is do a little bit after the fact. After I’ve written a bit of fiction, I will then look stuff up to see if that holds. In the case of Beatlebone, it certainly felt like I was skating on thin ice in some regards, because I was inventing events out of thin air for an actual historical figure. And it felt to me like I was going into elements of the most unfashionable literary genre of all, which is fan fiction! But I just kept saying to myself that if I stay true to the character, then I could get away with it. It was nice, toward the end of the process, when I was confident enough to open a book or two about Lennon, and I was reading a piece by a photographer who was quite friendly with Lennon, at that time, late 70s, and it talks about how he went off to Japan and booked himself into a hotel for the first time, and he’d started to go off on these little solo trips. So it sort of qualified the book for me, retrospectively. I thought that it was absolutely possible that he could go off on such a madcap expedition around this time in his life. It felt in keeping with something that he might have done.

Kane: Do you think it is misguided to see the goal of biographical fiction as an attempt to get to the biographical subject’s “true” or “authentic” self?

Barry: I think, again, this is something you’d have to take on a novel-by-novel basis, but in Beatlebone that’s exactly what I was trying to do. I was trying to give the real, pared-back essence of John Lennon and trying to get down to the very tips of his nerves and trying to expand out from there and show who I thought he was at this point in his life. It became quickly apparent that as I was writing this, with this particular goal in mind, that it was a book about making something. It was a book about how to try and make a piece of art: whether it’s a novel, or an album, or a painting, or film. It’s about going to the dark places—we don’t write, or draw, or make music because we are fine, we do it because we’re messed up, because life is meaningless, cruel, often disastrous and ridiculous and there is no fucking shape to it. That’s why we make art, as an attempt to put meaning and shape onto our lives. I guess that’s what I was trying to do with Beatlebone.

Kane: When writing about John Lennon, in Beatlebone, was there an internal censor at work in your mind as you were writing? What kind of ethical responsibility does an author have to the actual biographical subject?

Barry: It’s an interesting question, and it was absolutely on my mind from the start of the book. Do I have any right to do this? I think it felt to me that it was just about decorous because of the time span. The 1970s were getting to a point where they were moving into the realm of historical fiction. But no matter what I’m writing, I always think you should ask yourself the question: what gives me the right to do this? And I felt what gave me the right, with Beatlebone, is the fact that I was prepared to spend four years of my life in a shed in County Sligo using absolutely every ounce of ability that I could muster to do as good a job as I could on it. The fact of your ability and the fact that you’re prepared to do the slog, the thousands of hours it’s going to take to get something like this through to the finish. I guess those things gave me the sense that I was allowed to do it. Also the sense that I was going to keep a fidelity with the characte r in a way that felt right. It goes back to what I was saying earlier, that the book had to be nutty, loose, and wild. It had to be loose and wild enough so that no one would take it as something that actually happened in John Lennon’s life. And I felt that once I have him talking to a seal in a cave, nobody can take it as any kind of realism. This is going to be a nutty, surreal take. An awful lot of my work begins at a point where it looks broadly realistic, then very quickly moves out to the edges of believability, or likelihood.

Kane: In some biographical novels, there is a prefatory disclaimer that the characters are fictional, but you actually go much further in Beatlebone by providing the reader with details about your research methods and your writing processes in a first-person story-cum-essay. Was this because you felt that as a writer of biographical fiction you owed the reader an explanation, or were there other reasons?

Barry: It goes back to the point we were discussing earlier, about this being a book about making something and a book about the nature of artistic creation and how it works. There is nothing new in fiction, and it is as old as time to break the wall in this way. Laurence Sterne was doing it hundreds of years ago. I think in Victorian times they used to call it “baring the device” when the author intruded and appeared in the story. I thought it felt right for me to make an appearance and an awful lot of the time, when you’re writing fiction, it’s at that kind of gut level, day by day—does this feel right? Is this adding to the portrait, is this deepening the experience and intensifying it for the reader? Because I had another one of those dangerous moments when Cornelius and John had got on the road as a double act. I could see that page by page, it was great fun, and it was really working as that kind of story, and I thought I can just follow this through and give them lots of madcap adventures. But again I wanted to intensify from that point and just bring it up another level, or down another level, or deeper in. So it felt right to go with the baring of the device and showing how I went about it.

Kane: So the essay which appears in Beatlebone gives the reader an insight into not just the research methods you used but also brings to light some of the biographical and historical facts surrounding the back story of John Lennon and his purchase of Dorinish Island. It al...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Agency Aesthetics of Biofiction in the Age of Postmodern Confusion Michael Lackey

- 1 Positive Contamination in the Biographical Novel KEVIN BARRY, INTERVIEWED BY STUART KANE

- 2 Reflections on Truth, Veracity, Fictionalization, and Falsification LAURENT BINET, INTERVIEWED BY MONICA LATHAM

- 3 Resisting the “Dictatorship of the Present” in the Biographical Novel JAVIER CERCAS, INTERVIEWED BY VIRGINIA RADEMACHER

- 4 Sally Hemings’s Staircase: On Biofiction’s Afterlives BARBARA CHASE-RIBOUD, INTERVIEWED BY MELANIE MASTERTON SHERAZI

- 5 Voicing the Nobodies in the Biographical Novel EMMA DONOGHUE, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- 6 The Biographical Novel as Life Art DAVID EBERSHOFF, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- 7 Fictions of Women HANNAH KENT, INTERVIEWED BY KELLY GARDINER

- 8 The Bionovel as a Hybrid Genre DAVID LODGE, INTERVIEWED BY BETHANY LAYNE

- 9 Contested Realities in the Biographical Novel COLUM MCCANN, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- 10 The Biographical Novelist as Cultural Diagnostician ANCHEE MIN, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- 11 Speculative Subjectivities and the Biofictional Surge ROSA MONTERO, INTERVIEWED BY VIRGINIA RADEMACHER

- 12 Stitching up the Auto/Biographical Seam STEPHANUS MULLER, INTERVIEWED BY WILLEMIEN FRONEMAN

- 13 Complex Psychologies in the Biographical Novel SABINA MURRAY, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- 14 The Slant Truth of the Biographical Novel NUALA O’CONNOR, INTERVIEWED BY JULIE A. ECKERLE

- 15 Postmodernism and the Biographical Novel SUSAN SELLERS, INTERVIEWED BY BETHANY LAYNE

- 16 The Anchored Imagination of the Biographical Novel COLM TÓIBÍN, INTERVIEWED BY BETHANY LAYNE

- 17 I Believe in the Novel OLGA TOKARCZUK, INTERVIEWED BY ROBERT KUSEK AND WOJCIECH SZYMAŃSKI

- 18 Biographical Fiction and the Creation of Possible Lives CHIKA UNIGWE, INTERVIEWED BY MICHAEL LACKEY

- List of Biofiction Authors

- List of Interviewers

- Further Reading

- Index

- Copyright