![]()

David L Dawson & Nima G Moghaddam

1 Formulation in Action: An Introduction

Every individual experiences a complex array of events, situations, and circumstances within their lifetime that influence their psychological development and sense of personhood. Previous relationships and attachments, social roles and expectations, formative experiences and contexts, education, gender, culture, and countless other factors influence how we perceive ourselves, the world, and those around us. The nexus between our personal characteristics and experiences is where our individuality and relationality lie, and – from a psychological perspective – our preferences, biases, behaviours, peccadillos, hopes, and fears are forged within this complex milieu.

Psychological formulation (and its derivatives: case formulation and case conceptualisation) is the dynamic framework used by many psychological practitioners, in a range of applied contexts, to manage and understand this complexity. While operational definitions vary subtly between different theoretical approaches, formulation in mental health settings can be broadly understood as the process – and product – of applying psychological theory and concepts to understand the aetiology, meaning, and maintenance of the psychological difficulties we, and others, experience, and to identify ways in which these difficulties may be managed (see Corrie & Lane, 2010; Johnstone & Dallos, 2013, for a comprehensive overview of definitions).

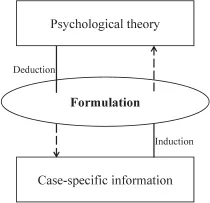

When individuals seek psychological support, formulation helps to guide identification of the processes, mechanisms, patterns, and so forth that appear to be contributing to the individual’s difficulties, assisting the psychological practitioner – and the individuals they are engaged with – to look through the complexity in order to recognise the latent factors and processes that appear key to understanding the distress and its maintenance. In this way, formulation can be thought of as the process of looking past the ripples and waves in order to understand the underlying currents and how best to navigate or harness them. Formulation is therefore considered central to the role of many applied psychological practitioners (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2005; Division of Clinical Psychology, 2010), facilitating the idiographic application of established psychological principles, and thus providing the essential bridge between psychological theory and clinical practice (e.g., Butler, 1998; Division of Clinical Psychology, 2010; Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa, & Chadwick, 2005). Figure 1.1 below depicts how formulation is informed by both inductive (information that is specific to the client) and deductive (broader psychological theory) processes. Importantly, there is a reciprocal influence between client-specific information and how a theoretical framework is applied, enabling idiographic responsivity (Persons, 2008).

Figure 1.1: In principle, formulation is constructed, validated, and adjusted through ongoing processes of deduction (drawing from, and applying, theory) and induction (grounded in data). Dashed lines indicate that theory informs assessment of case-specific information, and case information informs how theory is applied. Through case-based abstractions, case information also has potential to inform theory-building. While the above represents an idealised model of the reciprocal relationship between theory and practice, idiographic practitioner factors (e.g., experience, biases, etc.) are likely to influence how theory is deduced and applied in practice

The theoretical landscape that underpins applied psychology and therapy is constantly developing and evolving, informed by advances in basic theory, clinical observation, research, data, politics, and fashion; and individual practitioners are trained and embed their practice within different theoretical schools, traditions, and models. The process of formulating, or ‘applying theory to practice’ within a discipline as diverse, critical, and factional as applied psychology can therefore often seem unclear – particularly to students and trainees who are developing their own competencies in this area and who might be anxious to ensure that they apply the ‘right’ theory ‘correctly’. It is this process of applying psychological theory to clinical practice that is the central interest of the current volume.

The current volume has a strong applied focus and aims to demonstrate how a single case presentation (‘Molly’ – described in Chapter 2) can be formulated from a variety of theoretical perspectives. A single case description cannot capture the complexity, diversity, and dynamic processes of real-word clinical practice. However, by conveying multiple conceptualisations of a single client presentation, the salient features and unique aspects of each particular approach become more apparent – thus facilitating direct comparison and contrast between applied approaches. In this way, we wanted chapter contributors to illustrate how they apply psychological theory to their clinical practice, and to show their ‘working out’ – highlighting their initial thoughts and hypotheses, the case factors they consider salient and why, and how these issues sit within their approach – demonstrating ‘formulation in action’.

Given the issues related to applying the ‘right’ theory ‘correctly’, outlined above and elsewhere (e.g., Eells, 2011; Sturmey & McMurran, 2011), we also wanted to stimulate a critical dialogue between psychological practitioners of different theoretical positions. In this way, we aimed to further augment the compare-and-contrast function of each chapter, but also to demonstrate that all psychological formulations are open to critique – that the process of focussing on specific, theory-aligned factors within a case will inevitably entail the holding or over-looking of others – and to evince the multiple perspectives that practitioners have and how these can be debated.

There are a number of very useful resources currently available that critically examine the nature, function, validity, reliability, and utility of formulation within applied psychology (e.g., Bruch, 2015; Corrie & Lane, 2010; Eells, 2011; Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner, & Lucas, 2005; Flinn, Braham, & Nair, 2014; Johnstone & Dallos, 2013), consider its role within the profession more broadly (e.g., as an alternative to psychiatric diagnosis; Division of Clinical Psychology, 2013; Johnstone & Dallos, 2013), and demonstrate how various cases may be conceptualised from different perspectives (e.g., Sturmey, 2009). While individual chapter contributors address some of these broader issues, the current volume aims to build on the strengths of these existing resources by focussing on the applied and critical aspects of psychological formulation in action.

1.1 The Current Volume

Recent estimates indicate that there are now over 400 psychotherapy models, with varying levels of evidential support (Wedding & Corsini, 2013). The current volume describes a selection of psychological approaches commonly employed in contemporary clinical practice. This selection reflects broader trends ...