1

SO WHAT BOTHERS YOU ABOUT VACCINES?

There never was a golden age of vaccine acceptance. Immunization has never been universally accepted in any population as a method of disease prevention. The British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield’s 1998 Lancet article did not transform American parents’ perceptions of vaccines, although that article later became emblematic of vaccine skeptics in troubling ways.1 Vaccination has always had its detractors and its resistors, even as vaccinology in the twentieth century has been accepted wholeheartedly by mainstream medicine, public health, and most American parents as a primary method to prevent infectious disease.2

Historians have been clear on this issue in their analysis of vaccination in the United States and elsewhere. For example, James Colgrove shows that persuasive measures were necessary in the 1920s to convince wary American parents to vaccinate against diphtheria, which was a feared disease, although vaccine acceptance increased steadily through the 1930s.3 David Oshinsky writes in Polio: An American Story that frustration with parents not vaccinating their children for polio emerged quickly after the first few years that the Salk vaccine was available, suggesting that as soon as mass vaccination became federal policy, public health concerns about vaccine-wary parents emerged as well.4 For all the talk about “polio pioneers,” hundreds of thousands of parents did not volunteer their children for the experimental shots when they could have. Elena Conis’s Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship with Immunization demonstrates the rhetorical efforts of scientists and public health officials alike to get parents (and physicians!) to accept vaccines for the so-called mild diseases of childhood (measles, mumps, and rubella) in the 1960s and 1970s.5 Concerns about the pertussis vaccine were expressed beginning with its initial use in the 1930s, and came to prominence in the 1970s just as vaccine mandates for school entry swept the states and a British study suggested that the vaccine could cause neurological disorders. And in 1982, an NBC affiliate in Washington, DC, aired a documentary about vaccine dangers called DPT: Vaccine Roulette.6 This program is often credited with starting the contemporary antivaccination movement.7 Whether it did or not is up for debate.

This chapter describes the broad array of concerns about vaccination and viral and bacterial illnesses that have animated the public from the 1980s through the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century. The purpose here is to better understand what, precisely, the current perceived vaccination crisis is about, given existing data on vaccination attainment among children. This chapter and the next use news reporting as a way of gauging public concern, but also provide the opportunity to examine how reporting shapes public views. Ultimately, we can see how reporting has focused on certain positions about the nature of vaccine hesitancy and skepticism, and how the public has been deflected from its own complex expressed worries about vaccination.

Federal Vaccination Provision and Vaccination Attainment

Elena Conis and James Colgrove have written the two most authoritative histories of vaccination in twentieth-century and early twenty-first-century America, Vaccine Nation and State of Immunity (respectively). Readers interested in fuller historical treatments of vaccination in the United States should consult these sources. State of Immunity begins in the Progressive Era (early twentieth century) and focuses on the periodic oscillation between persuasion and compulsion in public health efforts to expand vaccination. Vaccine Nation focuses on the postpolio period, explaining how the expansion of vaccination in the last forty years of the twentieth century occurred in tandem with vaccine skepticism and outright refusal. Conis pays special attention to the social contexts and effects of federal action to broaden vaccine uptake, from John F. Kennedy’s Vaccination Assistance Act (1962) through Jimmy Carter’s Childhood Immunization Initiative (1977) and Bill Clinton’s Vaccines for Children program (part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993). Both of these sources offer insights into how past federal action on vaccination provides a context for the current vaccination controversy.

The polio vaccine was the first to be provided nationally through a coordinated federal effort. When vaccine proponents worked to ensure better immunization rates against poliomyelitis in the 1960s, they confronted an old challenge—middle-class citizens were more likely to line up themselves and their children for shots than were poor people. In the early 1960s, Kennedy’s Vaccination Assistance Act thus targeted poor children, those older than five years of age, and provided the four vaccines that were then available: polio, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus. That act was renewed during the Johnson administration, but the funding mechanism changed under President Nixon to a set of block grants to states, some of which chose to put the funds to other public health uses. In the 1970s, Jimmy Carter’s plan, which included shots for seven vaccine-preventable diseases (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, rubella, and mumps—the latter three having been developed since 1963), also focused on poor children. Carter’s Childhood Immunization Initiative relied more on volunteers and attempted to keep the federal footprint subordinated to state oversight. Conis points out that the Carter initiative involved significant moralized messaging that identified parental ignorance, misunderstanding, and lack of attention to the importance of vaccines as reasons parents didn’t immunize their children. Thus, the 1990s were not the first period in which parental belief or disposition was understood to be a problem in achieving optimal vaccination levels nationally.

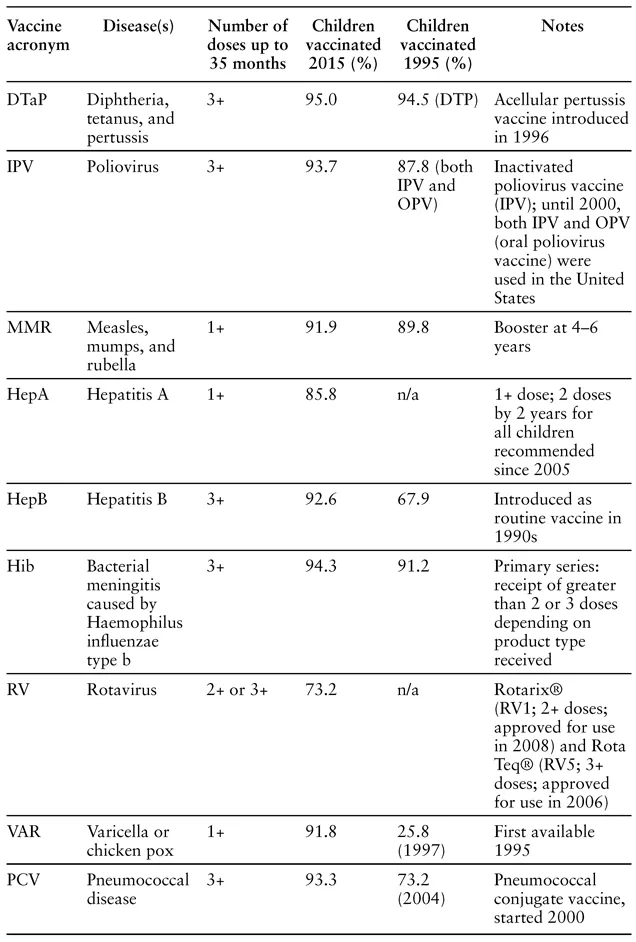

After leveled or diminished funds for childhood vaccination during the Reagan administration, and a measles epidemic from 1989 through 1991, reporting on US vaccination policies often compared them (rather negatively) to those of poor countries. Bill Clinton’s plan, like his overhaul of welfare a few years later, relied on what was termed personal responsibility, even though it was clear at the time that vaccination rates were related to socioeconomic status. Regardless of the semantics, the program has been successful in diminishing nonvaccination among the poor and improving rates overall. A comparison of vaccination rates from the mid-1990s to today demonstrates that over a twenty-year period that began in 1995, significant gains were made in improving rates of MMR and polio vaccination for infants up to thirty-five months, and that most other childhood vaccination rates have improved marginally over time. In 2015, only 0.8 percent of US children under the age of three years received no vaccinations at all.8

TABLE 1. National vaccination rates at 35 months

Sources: National Immunization Survey (NIS)—Children (19–35 months), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC.gov, https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/child/index.html; Holly A. Hill et al., “Vaccination Coverage among Children Aged 19–35 Months—United States, 2015,” MMWR 65, no. 39 (October 7, 2016): 1065–71.

The data in table 1 demonstrate that, contrary to popular belief, this country is not currently experiencing a national crisis in vaccination attainment. This is not to say that clusters of unvaccinated children and adults do not pose a public health risk, as public health officials are quick to point out, or that there is not room for improvement in these immunization rates (at least from the perspective of public health). The data shown in the table do not include the final boosters in some series, and these are often the very shots that are most difficult to attain, as toddlers and young children go to the doctor less frequently than infants, and other logistical obstacles present themselves. In addition, the table does not include some vaccines that target adolescents, like the HPV or meningococcal vaccines. Nevertheless, the data presented here suggest that hyperbolic claims of increasing rates of unvaccinated children across the nation are not based on data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A Short History of Vaccine Concerns since 1980

In 1980 seven vaccines were given routinely to children in the United States to prevent the following illnesses: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, and polio. At the time these were usually administered in two shots and a liquid dose: DTP, MMR, and oral polio.9 There were also boosters. By the end of this period, however, the recommended vaccination schedule for US infants and children had ballooned significantly to shots against a total of sixteen diseases. (It is difficult to quantify exactly the number of shots, given the variety of multiple-vaccine formulations that children can receive and that the number of doses recommended varies according to the age of the child.) The historian Mark Largent argues that the sheer number of vaccines given to infants and children is a primary, legitimate concern.10 Understanding how and why vaccinations have increased in number is helpful in getting a handle on a generalized heightened anxiety about infant and childhood vaccines.

Historically, legislation has set the context for steadily increasing recommendations and mandates for infant and childhood vaccination. In the early 1990s, the Clinton initiative made it likely that vaccine manufacturers would seek recommended status by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and try to be on the list of vaccines mandated for school entry. The Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act of 2010 expanded on Clinton’s program, requiring that insurance plans cover ACIP-recommended vaccines for children without cost to them or their families. What this means is that getting a new vaccine onto ACIP’s recommended list is a priority for vaccine manufacturers, because it ensures a reliable stream of vaccine-eligible children or adults whose immunizations are covered by insurance. (Better yet is getting onto the list of vaccines mandated for school entry, which is often a consequence of being put on the list of recommended vaccines.) This feature of federal legislation, while clearly making vaccinations affordable and thus accessible for children and adults from lower socioeconomic strata, also created the context for parental resistance to childhood vaccines, simply because there were so many added to the schedule and many are often administered at the same office visit. Immunization overload thus became a focus of parental concern in the early twenty-first century.11

But while increased immunizations for infants and children is an important part of this story, it is not the only, or necessarily the most important, part. In what follows I trace a history of vaccination and infectious disease concern that tacks back and forth between fears of vaccine shortage in the context of disease outbreak and nervous attention to vaccine risk. It is important to understand that these tendencies occur together, suggesting ambivalence about medicalized approaches to health at the same time that illness is feared. The high vaccination attainment demonstrated in table 1 came about in the context of growing concerns about vaccination and the emergence of what we think of today as a highly charged vaccination controversy in the public sphere. What we have, then, is something of an enigma—high attainment in the context of growing concern. What we normally don’t think about, however, is the range of concerns about vaccines that have been raised historically and how those relate to what sometimes seems a narrow focus on childhood vaccines and, in particular, the possibility of a connection between childhood vaccines and autism. This section of the chapter traces concerns about vaccines that were documented in news reporting from the early 1980s through 2015.

The acceleration of vaccine approval and insertion into the recommended schedule during the 1980s and 1990s coincided with the emergence of the AIDS epidemic and the changes it wrought on drug development regulations and activist medical culture at large. Because developments concerning HIV/AIDS were so prevalent in news reporting during this period, I have not included them in this discussion, but they do provide a context for vaccination controversy as it emerged. It also bears noting that in 1976, during a time when there were significant concerns about the whole-cell pertussis vaccine causing neurological damage, a vaccine against a strain of swine flu was thought to have caused increased incidence of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), a temporary form of paralysis. A huge rollout of swine flu vaccinations during Gerald Ford’s presidency was halted when GBS was thought to be caused by that vaccine.

What should be clear by this point is that concerns about vaccines did not arise de novo in the 1980s or 1990s but have persisted since the rollout of federally supported vaccination programs in the 1950s. Indeed, many historians have traced long-standing concerns back to the 1790s, when Edward Jenner invented the smallpox vaccine. But the thirty-five-year period from 1980 to 2015 is long enough to demonstrate significant and diverse worries about vaccines in the United States, as well as the triumphant development of many vaccines that have lowered infant morbidity and mortality.

The early to mid-1980s saw increased concerns about vaccines in the media as well as the development and approval of two important vaccines for children. In 1982 an NBC affiliate in Washington, DC, aired DPT: Vaccine Roulette, a documentary about vaccines and their dangers. Excerpts were also shown on the Today Show. The documentary followed concerns about the whole-cell pertussis vaccine from the 1970s, when British researchers claimed that it caused neurological damage. A vaccine safety group, Dissatisfied Parents Together (with the same acronym, DPT), established itself at this time. (This group later became the National Vaccine Information Center, one of the country’s largest and most vocal vaccine safety organizations, with an expansive website.) A few years later, in 1985, a vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib, a bacterial disease) was released. Before the vaccine, Hib was a major cause of meningitis in infants. Updated in 1987, the vaccine allowed physicians to rule out meningitis when infants presented at emergency rooms with high fevers. And in 1986, a recombinant vaccine for hepatitis B (Hep B) was developed as an improvement over the older vaccine, released in 1981, which was made from human blood products.

From 1989 to 1991, tens of thousands of Americans were sickened by a measles outbreak that spread across the United States. The outbreak was thought to be the result of low vaccination rates that were themselves the outcome of more than a decade of lagging attention to childhood vaccination attainment. The outbreak motivated Bill Clinton, once he was president, to initiate the Vaccines for Children program in 1993, which aimed to reduce socioeconomic and racial disparities in vaccine availability and receipt by lowering logistical barriers to vaccination for poor children. In the public imagination, however, the outbreak was partly overshadowed by the Gulf War, also known as Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. The war was a response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and involved a coalition of forces led by the United States. Gulf War Syndrome, a controversial diagnosis involving numerous complaints (including fatigue, diarrhea, rashes, cognitive difficulties, and other symptoms), was linked by some to the anthrax vaccines given to soldiers deployed to the Persian Gulf. Thus, just as in the early to mid-1980s vaccine development occurred in tandem with vaccination concerns, so too at the beginning of the 1990s worries about epidemic-level infectious disease emerged at the same time that new illnesses were being blamed on vaccination receipt.

The pattern would continue throughout the decade, as new vaccines were released and included in the recommended schedule for infants and children. In 1991 ACIP recommended a change in the schedule for hepatitis B vaccination, with a goal of total disease elimination in the United States. Trying to vaccinate adults and those at risk of hepatitis B had not worked to lessen transmission in the United States in line with CDC goals. As a result, ACIP recommended universal childhood vaccination against Hep B that would begin, optimally, on the day of their birth. In 1995 a vaccine against chicken pox (varicella) was added to the recommended immunization schedule for children, although most states would not include it as a mandatory vaccine for school entry for a few more years. In 1996 an acellular version of the pertussis vaccine replaced the whole-cell version, partly in response to concerns about neurological injury presented in DPT: Vaccine Roulette.

Thus, one new vaccine, one redesigned vaccine, and a new schedule for yet another preceded the emergence of significant new concerns about childhood vaccination in the ...