![]()

Part One

The Changing Face of Talent

For ambitious, educated women in emerging markets, the future has never looked brighter. New opportunities beckon, calling for and rewarding their skills and their determination to use them. Employers who cultivate their talent find their efforts reciprocated with impressive levels of loyalty. We'll explore the unprecedented advantages emerging markets women bring to the workplace in Chapter 1.

But few companies can afford to be complacent about this rich lode of talent. We cannot emphasize enough the power of the societal forces tethering women's career aspirations, grounding their ambition and causing too many women to settle for a dead-end job or quit the workforce altogether. We'll describe the nature of these family-rooted “pulls” and cultural “pushes” in Chapter 2.

![]()

1

Unprecedented Advantages

When Maria Pronina graduated from Nizhni Novgorod Linguistic University in 1995, she expected to follow the conventional career track and become an English language teacher. Disappointed with the low salary, however, she switched jobs and started to work as an interpreter, first for the regional government and then for a local company. She acquired a management degree and became a supervisor, and then she moved to a multinational technology company.

Pronina still remembers the moment when she realized that her career horizons had no limits. “I really did not believe that coming from a very low level I had a real chance to make it rapidly. But at my first annual performance assessment, I suddenly understood I could be recognized and could do well. That was the turning point for me.”

Today, Pronina oversees fourteen direct reports and four hundred contractors as facilities and services team manager for Russia/CIS at Intel. Her ambition is to stay with her employer—and do even more. “My employer is doing a lot for my development and provides almost everything I would like to have. I would like to stay at this company but be responsible not only for Russia and CIS but also Europe.”

Talented women in emerging markets are ahead of the curve in unexpected ways. Like Pronina, they see work not as a stopgap measure to fill the time between marriage and motherhood but as an opportunity to realize their ambitions.

This chapter explores the remarkable combination of advantages that talented women in emerging markets bring to the workplace: impressive qualifications, ambitious career visions, and great passion and commitment to their work.

EDUCATIONAL EXCELLENCE

The World Economic Forum's 2010 Annual Gender Gap Report tracks gender parity for 134 countries along four dimensions: education, health, economic participation and opportunities, and political empowerment.1 In the BRIC countries and the UAE, the overall gender gap has consistently narrowed, and this shift is most apparent in education.

Interestingly, the spark for many women was triggered by their parents, who recognized the value of an education in a changing world and encouraged their daughters to excel in their studies, either at home or abroad. For many families, like Hiroo Mirchandani's, educational achievement was expected of children of both sexes. “We were brought up measured on how we did in school,” recalls Mirchandani, who grew up in New Delhi. “It didn't matter if you were a boy or a girl. What was expected was that you came at the top of the class.”

Other parents pushed their daughters to overcome their own shortcomings through education. Woman after woman in our focus groups and interviews had a story similar to Lisandra Ambrozio's. When Ambrozio's mother was a girl, her dream was to learn English. Her mother, however, wanted her daughter to learn to play the piano. Ambrozio's mother grudgingly studied piano for twelve years—“She hated it,” Ambrozio recalls—until she married. “And she never played the piano again.” But she never forgot her resentment at being denied the chance to learn another language, and as soon as Ambrozio could read, her mother asked whether she'd like to take English classes. When Ambrozio said yes, her mother was overjoyed. “Great!” Ambrozio remembers her exclaiming. “I'm going to pay for your English courses myself, because I think this will be good for your career and your personal life.” As a result, Ambrozio was fluent in English before she went to Pontificia Universidade Catolica, Brazil's top private university, where she received her undergraduate degree and MBA.

Ambrozio's father also supported her educational aspirations. Ambrozio's dream was to take a year-long extension course at the University of California, Berkeley. “I was working and saving money for a couple of years,” Ambrozio says, but when she finally accumulated enough money to pay for the course and her living expenses, Brazil suffered a massive currency devaluation. Half of her savings were wiped out. Ambrozio's father hadn't been happy about the prospect of his daughter's leaving the country, but he knew how much it meant to her. “He said, ‘Okay, you pay for half of the course and I'll pay for the other.’ Greeeeat father!” Ambrozio exclaims.

Today, Ambrozio is the human resources director for Pfizer, Brazil. Her brother is a civil engineer, and her sister is a lawyer. Ambrozio has never forgotten her father's action or what it represented. “This is one of the most admirable things that my father did,” she muses. “He invested in our education.”

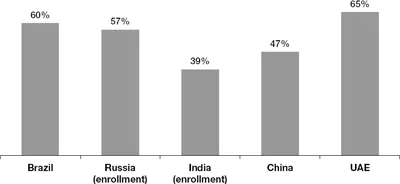

This groundswell of expectation, encouragement, and support from both parents endorses one of our most striking findings: that women are flooding into university and graduate schools in record numbers. Just as in the United States, where women college graduates now outnumber men, there is an “achievement gap” in three of our target geographies: women represent 65 percent of college graduates in the UAE, 60 percent in Brazil, and in China they are already 47 percent of this group (see figure 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1

Percent of women in tertiary education

Source: World Bank Education Statistics Database.

It is no surprise that in Russia, where Communism promoted universal access to education, 86 percent of women aged eighteen to twenty-three are enrolled in tertiary education—compared with 64 percent of men the same age—and the numbers in the other BRIC markets are also impressive.2 More than one-third of women in the appropriate age group in Brazil and the UAE are enrolled in tertiary education, a percentage notably larger than that of their male counterparts.

In China and India, with far larger and less urbanized populations, the overall percentage of women in this age group enrolled in colleges and universities is lower—23 percent and 10 percent, respectively—but the interesting story is who has the determination to go beyond the initial diploma. Half the Indian women in our sample hold graduate degrees, outstripping men by 10 percentage points, and the number of Chinese women with graduate degrees is virtually equal to the number of Chinese men. As one of the women we interviewed explained, “There was a time in India when people saved up money for their daughter's marriage or for their son's education, but the urban middle-class community in India doesn't do that anymore. Today, for a son or a daughter, the priority is education.”

The BRIC/UAE education figures are impressive also in their sheer scale, because the actual number of university graduates in these countries has increased at a phenomenal rate. Thanks to the rapid expansion in the number of institutions of higher education, an area that has experienced reinvigorated government and private sector focus in recent years, higher education enrollment in China has more than tripled since 2000, and the number of doctoral degrees awarded annually rose sevenfold between 1996 and 2006.3 In India, the number of universities has doubled since 1990, and the government has committed to boosting higher education spending ninefold, to $20 billion annually in the five-year period that began in 2007. This colossal investment will be directed toward seventy-two new postsecondary schools, including eight new Indian Institutes of Technology, seven new Indian Institutes of Management, five new Indian Institutes of Science, Education and Research, and twenty new Indian Institutes of Information Technology.4

The broadening access to higher education has been paralleled by vast improvements in the quality of education available in BRIC countries and the UAE. It's no secret that the quality of BRIC and UAE university graduates has been uneven, to say the least, with many degree holders unprepared to succeed in a competitive multinational environment. Each year, for instance, India produces as many young engineers as the United States, and Russia graduates ten times as many finance and accounting professionals as Germany; yet the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that a mere 25 percent of professionals in India and 20 percent in Russia are top-quality, “ready” talent; similarly, in China it is estimated that fewer than one in ten university graduates is prepared to succeed in a multinational environment.5 Until very recently, the smartest students in developing economies sought entry to the most prestigious universities in the United States and Western Europe.

Today, though, emerging markets can boast about their own ivory towers. Six of China's universities are ranked among the top two hundred in the world, as are two each in India and Russia.6 The shift in quality is even more pronounced at the graduate level, with the Indian School of Business (ISB) in Hyderabad and the China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) in Beijing recently included in the top twenty-five of the Financial Times' Global MBA rankings in 2010, taking their place alongside such storied institutions as Harvard Business School, Wharton, and the London Business School.7 Notably, 26 percent of the students at ISB and 33 percent at CEIBS are women, a figure on par with representation at top MBA campuses in the developed world.8

Furthermore, many Western-based business schools are partnering with or opening their own campuses in emerging markets. France-based INSEAD, one of the world's top-ranked business schools, has offered full-time MBA degrees at its Singapore branch since 2000; it opened an executive education center in Abu Dhabi in 2007. This is no isolated trend: University of Chicago's Booth School of Business has had an executive MBA program based in Singapore since 2001, and Harvard Business School established a presence in Shanghai in 2010.9 If the enrollment trends above are any guide, a significant percentage of the students will be women.

The good news for global companies: educated women in emerging markets are already important sources of skills and expertise. The rising demand for advanced education, the corresponding opportunities now available in their home countries, and the increasing number of women taking advantage of these opportunities will indelibly change the face of talent in the years ahead.

ASPIRATION AND AMBITION

“When I was growing up, I never thought I would be someone,” confides Aisha al-Suwaidi. Both of her parents were uneducated: her father was a fisherman in Sharjah, her mother had gone to elementary school for only a few grades. As a result, after the UAE became independent in 1971, “both my parents pushed all of their children to get an education.”

Al-Suwaidi's timing couldn't have been more fortuitous. The local economy was booming, foreign universities were establishing UAE satellites, and al-Suwaidi was in the thick of it, earning first a business degree and then switching her focus to career counseling.

Now the director general for Dubai Women Establishment, al-Suwaidi is passionate about improving opportunities for women in the UAE. “Political advocacy is one of the most important things I work on. I'm talking about being able to deliver something unique, which will impact a lot of people, for which you'll be remembered for generations.”

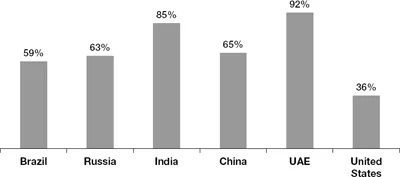

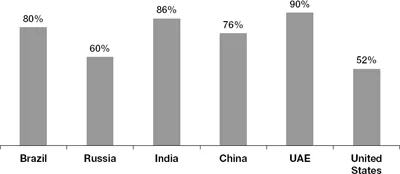

Highly educated women the world over are ambitious, but the widespread nature of ambition and aspiration among women in the BRIC countries and the UAE is extraordinary (see figure 1-2). The majority of women surveyed consider themselves “very ambitious,” compared with only 36 percent of their American counterparts. Aspiration levels are equally impressive (see figure 1-3).

Armed with their freshly minted diplomas, women in emerging markets are hungry to prove themselves, even more so than their male classmates. One HR leader for a global management consultancy that recently reentered the Chinese market says, “For the majority of college grads, career is a very important thing, but we often find female candidates to be as competitive, if not more so, than their male counterparts.” So many highly qualified women are applying for jobs, in fact, that her boss jokingly remarked, “Finally, here's one place where we don't have to worry about equal opportunity.”

FIGURE 1-2

Percentage of women with high level of ambition

FIGURE 1-3

Women who aspire to a top job

These impressive levels of aspiration are no accident. The fast-evolving nature of the emerging market economies amplifies a sense of possibility and optimism. You only have to open your eyes and look around to see the proof that dreams can become concrete reality, says Alpna Khera, a senior commercial leader running a $30MM P&L at GE's transportation division in India. “People have created fortunes in this market, and it is encouraging to know that one can create opportunities for oneself and achieve great things,” she says. Her own career trajectory is defined by an unambiguous desire for continued advancement within leadership ranks. Khera was the first woman in India to work in a gas-based power plant—at a time when there was no separate women's washroom—and aspires to eventually be the head of GE Energy in India.

Many of the women we spoke to were keenly aware of their role and participation at a significant point in the history of their countries, in essence being part of a huge national development project. The adrenaline rush of being front and center in a tremendous transition fuels ambition in a big way. “In Europe, you would work on refining a company's business strategy. Here, you have the opportunity to be involved in high-impact projects that are reshaping countries and the region as a whole,” explains Leila Hoteit, an Abu Dhabi-based principal at Booz & Company working with public sector entities.

Part of what propels the extraordinary ambition of women in emerging markets is a seismic shift in their family roles and social status. The regions' rapid economic growth has transformed gender roles in a way that the West tends to underestimate, not only by encouraging female participation in the workforce but also by enabling women to move into management positions in impressive numbers. They can aspire to high-flying careers because of another startling change on the home front: on average, women in BRIC countries have fewer than three children, and in China and Russia fewer than two—a huge decline from past generations.10 (We discuss the details of this metamorphosis in the chapters focusing on specific countries.)

As women move into management positions, a startling number are earning salaries equal to or greater than their spouses. In Brazil, China, Russia, and the UAE, we found that nearly 20 percent or more of women working full time outearn their spouses. The power of the purse, even more than educational opportunities and career aspirations, is helping women break through the social traditions that held back many in their mothers' generation. After all, a mother-in-law is less likely to expect her son's wife to wait on her hand and foot when she's bringing home a big share of the family income.

With living costs escalating in emerging markets, especially in urban areas, women's contribution to household expenses is not only appreciated but also indispensable. Six of the thirty most expensive cities in the world are in Russia, China, and Brazil.11 “Women have to work because the cost of living in Moscow and St. Petersburg is very expensive,” says Veronika Bienert, a senior executive at Siemens Russia. Similarly, a Beijing-based HR manager notes, “In China today, there is no way that only the husband can work and the wife stay home, because you need the income on both sides.”

With financial need trumping cultural pressure, the majority of women in our sample do not experience social pressure to quit work after they marry or even upon the birth of their first child, with the exception of India, where traditional social norms adhere far more closely than elsewhere. Yet even there, change is imminent. One Indian executive explained that her entire family supported the choices she has made as a working mother: “My husband says, ‘There's no way you are leaving your job. You're too driven, you're well qualified, and you have ambition.’ My mother wanted to study and couldn't, so she pushed me to achieve things she was not able to. I would never consider leaving my job” for fear of disappointing her...