- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

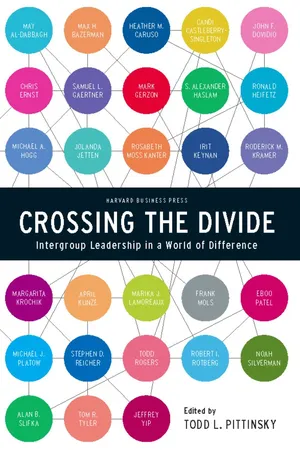

Bringing groups together is a central and unrelenting task of leadership. CEOs must nudge their executives to rise above divisional turf battles, mayors try to cope with gangs in conflict, and leaders of many countries face the realities of sectarian violence.Crossing the Divide introduces cutting-edge research and insight into these age-old problems. Edited by Todd Pittinsky of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, this collection of essays brings together two powerful scholarly disciplines: intergroup relations and leadership. What emerges is a new mandate for leaders to reassess what have been regarded as some very successful tactics for building group cohesion. Leaders can no longer just "rally the troops." Instead they must employ more positive means to span boundaries, affirm identity, cultivate trust, and collaborate productively.In this multidisciplinary volume, highly regarded business scholars, social psychologists, policy experts, and interfaith activists provide not only theoretical frameworks around these ideas, but practical tools and specific case studies as well. Examples from around the world and from every sector - corporate, political, and social - bring to life the art and practice of intergroup leadership in the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

part I

Insights and Concepts

1

Leadership Across Group Divides

Common Group Identity

John F. Dovidio

Yale University

Samuel L. Gaertner

University of Delaware

Marika J. Lamoreaux

Georgia State University

GROUP LIVING represents a fundamental survival strategy, developed across human evolutionary history, that characterizes the human species. For long-term survival, people must be willing to rely on others for information, aid, and shared resources; they must also be willing to offer information, give assistance, and share resources with others. Group membership provides necessary boundaries for mutual aid and cooperation.

Group Membership: Social Categorization and Social Identity

Improving Intergroup Relations: The Common In-Group Identity Model

Challenges of a Superordinate Identity: Multiple Categorizations and Identities

Table of contents

- Also by

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction - Intergroup Leadership

- part I - Insights and Concepts

- part II - Tools and Pathways

- part III - Cases in Context

- Index

- About the Contributors