![]()

Part I

Conceptual Introduction

![]()

One

The Nature of Institutional Voids

in Emerging Markets

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM holds that the diffusion of skills, processes, and technologies throughout global markets is resulting in convergence; the gap between emerging economies and their more developed counterparts is quickly closing.1 This optimism has been bolstered by the development of high-tech global supply chains and the offshoring of professional services, but market transition and emergence often take more time than most decision makers anticipate. What is emerging in emerging markets is not only their forecast potential or liberalizing investment environments but also the institutional infrastructure needed to support their nascent market-oriented economies.

Institutional development is a complex and lengthy process shaped by a country’s history, political and social systems, and culture. Dismantling government intervention and reducing barriers to international trade and investment can spark market development, but they do not immediately produce well-functioning markets. The world may be becoming flatter, as columnist Thomas Friedman has argued, but the landscape of emerging markets, in particular, remains deeply striated by institutional legacies.2

Many observers of emerging markets are quick to recognize that, for them to be fully developed, it is important to create physical infrastructure—roads, bridges, telecommunication networks, water and sanitation facilities, and power plants. Without adequate physical infrastructure, it is hard for participants in product, labor, and capital markets to function effectively. However, less recognized is the importance of institutional development that underpins the functioning of mature markets.

The most important feature of any market is the ease with which buyers and sellers can come together to do business. In developed markets, a range of specialized intermediaries provides the requisite information and contract enforcement needed to consummate transactions. Most developing markets fall short on this count. Investors and companies quickly realize that these regions do not have the infrastructure, both physical and institutional, needed for the smooth functioning of markets. It is difficult for buyers and sellers to access information to find each other and to evaluate the quality of products and services. When disputes arise, there are limited contractual or other means, such as arbitration mechanisms, to resolve these issues. Because of a tremendous backlog of cases, resolving disputes in Indian courts, for example, can take five to fifteen years.3 Some joke that “if you litigate here, your sons and daughters will inherit your dispute.”4 Anticipation of these transactional difficulties also hinders contracting. We use the term institutional voids to refer to the lacunae created by the absence of such market intermediaries.5

To understand institutional voids in more concrete terms, consider the plight of an independent traveler from the United States visiting an emerging market on vacation. Beyond the challenges of operating in an environment having a different language, culture, and currency, the traveler also must navigate a different way of doing business, even as a tourist. Accustomed to booking flights through Expedia, Orbitz, or Travelocity, choosing hotels based on easily accessible and reliable reviews, obtaining travel-planning assistance from the AAA, paying for goods and services with a credit card in virtually any location, purchasing goods that meet enforced regulatory standards and possess enforceable warranties, paying taxi drivers according to standardized rates, receiving flight status updates by mobile phone text message, and finding restaurant phone numbers by simply dialing 4-1-1, the traveler must adapt to a different environment in the emerging market.

Although they might come in different forms, most other developed markets, such as European countries or Japan, have a comparable tourism market infrastructure to that of the United States. The institutional arrangement of an emerging market’s travel and hospitality marketplace, however, differs in fundamental ways. Internet-based airline ticket vendors, published travel reviewers, telephone directory assistance providers, credit card payment systems, and other such intermediaries are businesses, but they are also part of the U.S. market infrastructure. They help bring together buyers and sellers of travel services. (Nonprofit organizations, such as AAA, can also serve as market intermediaries, and governments provide many intermediary functions through regulatory bodies and civic services.)

In developed economies, companies can rely on a variety of similar outside institutions to minimize sources of market failure. Emerging markets have developed some of these institutions, but missing intermediaries are a frequent source of market failures. Informal institutions have developed in many emerging markets to serve intermediary roles. To reach rural consumers in India, for example, many brands rely on traveling salespeople to promote products in villages that have limited television, radio, and newspaper penetration. Salespeople stage live, infomercial-like performances out of the backs of trucks, explaining products while entertaining crowds with skits and banter. One such salesman, profiled in the Wall Street Journal, traveled more than five thousand miles per month, moving from village to village pitching products as wide ranging as tooth powder and mobile phones.6

Although some informal institutions may look like functional substitutes for the intermediaries found in developed markets, they often exist on an uneven playing field—accessible only to certain local players. A local loan provider might seem like a substitute for a venture capital industry, but only if the loan provider evaluates applicants on their merits or business plan. Seldom are informal market intermediaries truly open to all market participants.

Institutional voids come in many forms and play a defining role in shaping the capital, product, and labor markets in emerging economies. Absent or unreliable sources of market information, an uncertain regulatory environment, and inefficient judicial systems are three main sources of market failure, and they make foreign and domestic consumers, employers, and investors reluctant to do business in emerging markets. When businesses do operate in emerging markets, they often must perform these basic functions themselves.

Institutional voids, however, are not only roadblocks. They are also palpable opportunities for entrepreneurial foreign or domestic companies to build businesses based on filling these voids. To return to the example of the travel industry, Ctrip.com has emerged as China’s leading travel booking Web site, offering services similar to those of Expedia, Orbitz, and Travelocity. Established in 1999, Ctrip.com fills voids by aggregating hotel reservation and airline ticket information, providing rates and schedules, and offering a platform for customers to complete transactions—a powerful proposition in a market without a well-developed network of alternative intermediaries, such as travel agents.7 Ctrip.com registered $210.9 million in revenue in the year ending September 30, 2008, with a profit margin of 31.8 percent.8 Listed on NASDAQ, the company had a market capitalization of $1.3 billion as of January 13, 2009.9 The significant value that can be created by intermediary-based businesses illustrates the importance of such market institutions—and the cost of their absence. Transaction costs in markets, the role of market institutions in mitigating them, and the challenges of designing market institutions have been analyzed by several Nobel Prize–winning economists: Ronald Coase, Douglass North, George Akerlof, and Oliver Williamson. We draw on this vast literature in institutional economics in the following discussion.

Why Markets Fail and How to Make Them Work

Transactions vary in difficulty. It is generally easier to transact in developed than in developing markets. For example, renting a car in Boston is far easier than it is in Mumbai, São Paulo, or Ankara. Purchasing a home in London, although increasingly cost prohibitive, is a much easier feat than buying real estate in Moscow, with its infant mortgage market. Even in developed economies, however, there are degrees of transactional difficulty. For instance, U.S. consumers find it far more complex to buy health-care services than to buy groceries or consumer electronics.

Transaction costs, which offer one measure of how well a market works, include all the costs associated with conducting a purchase, sale, or other enterprise-related transaction. Well-functioning markets tend to have relatively low transaction costs and high liquidity, as well as greater degrees of transparency and shorter time periods to complete transactions.

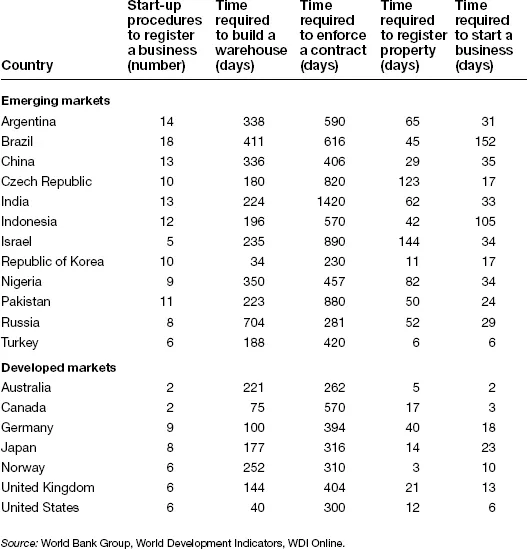

The World Bank Group’s World Development Indicators highlight the variance in market performance between countries. Brazil, China, and India required more than twice the number of start-up procedures to register a business in 2007 than the six procedures required in the United States; Australia required only two. Another transaction cost measure is the time required to build a warehouse. A warehouse could be completed in leading developed countries in fewer than 200 days in 2007—in some cases far fewer—whereas in major developing markets such as Brazil, China, India, and Russia, it took 411, 336, 224, and 704 days, respectively. Other indicators, such as time to enforce a contract, time to register property, and time to start a business, also suggest higher transaction costs in many developing regions (see table 1-1).

All markets, irrespective of development phase, are less than perfectly efficient. Compared with emerging markets, however, developed markets are more likely to approach consistent standards for efficient transactions. Conducting even simple transactions in developing economies can be a time- and resource-intensive process, posing hazards for those expecting the fluidity of developed markets.

The challenge of transacting in the absence of well-developed market infrastructure is best illustrated through the Nobel Prize–winning economist George Akerlof’s example of a used car market. Akerlof’s work showed the difficulty of creating a well-functioning market when the quality of goods and services being bought and sold is uncertain.10 After owning and maintaining a car for five years and driving it for sixty-five thousand miles, the seller knows the condition of the car far better than the buyer. Unfamiliar with the car and its seller, the buyer will therefore approach the transaction with a degree of apprehension and mistrust. Is the seller selling a used car in decent working condition, or is he peddling a car with inferior quality relative to its price—a lemon? Is the car worth the price being asked?

TABLE 1-1

Comparing transaction costs in emerging and developed markets (2007)

The difference in knowledge about the car between buyer and seller—what economists call information asymmetry—and lack of trust make the buyer wary of taking the seller’s claims of quality at face value. As a result, a prudent buyer generally is reluctant to pay the price asked by the seller. Given these conditions, how can the buyer and seller consummate the transaction to their mutual satisfaction?

One obvious solution, practiced in ancient bazaars for centuries, is price bargaining. Suppose the seller is asking $10,000 for the car. The buyer can respond by offering a lower price—say, $6,000—to compensate for the variety of unknowns. If the seller finds the price acceptable, the transaction will take place; otherwise, the seller will walk away.

But simple bargaining leaves most market participants unsatisfied. Why? The seller has a pretty good idea of the true value of the car, so he will be happy with the $6,000 offer from the buyer only when it exceeds the car’s true intrinsic value. This, of course, means that the buyer would have overpaid for the car even though the bid price is substantially lower than the asking price. In contrast, if the seller were honestly representing the facts of the car’s quality and asking a reasonable price given its true value, he would find the $6,000 bid from the buyer unattractive, prompting him to walk away from the deal. Thus, with a strategy of bargaining for a price lower than the asking price, the buyer will consummate only deals that are systematically adverse to his interests.11

This type of used car market leaves buyers unhappy, because they systematically overpay for any given level of quality. Sellers of genuinely high-quality cars will find no takers, because the market-clearing prices are always lower than sellers’ assessment of fair prices. The only participants who will be happy are sellers who sell lemons at an inflated price. Clearly, this type of market will not last very long because sellers of genuinely high-quality cars will learn not to use it, and buy...