![]()

P A R T ONE

TRANSLATING THE STRATEGY TO OPERATIONAL TERMS

Do YOU NEED A FINANCIAL PLAN? Call any of the major accounting firms and ask for their assistance. The results they deliver will be strikingly similar. Each plan will have a pro forma income statement, balance sheet, cashflow forecast, and capital plan. The actual contents of the plans may differ, based on the knowledge and experience of the accountant, but the structure will be the same.

Look at how the situation changes when you need a strategic plan. You can go to any of the major strategy consulting firms for help, but the results they deliver will not be similar in any way. One firm will look at your portfolio of businesses. Another will focus on processes. A third may analyze customer segments and value propositions. Others will stress shareholder value, core competencies, e-strategy, or change management. Unlike financial management, strategy has no generally accepted definitions or framework. There are as many definitions of strategy as there are strategy gurus.

Why is this a problem? In this era of knowledge workers, strategy must be executed at all levels of the organization. People must change their behaviors and adopt new values. The key to this transformation is putting strategy at the center of the management process. Strategy cannot be executed if it cannot be understood, however, and it cannot be understood if it cannot be described. If we are going to create a management process to implement strategy, we must first construct a reliable and consistent framework for describing strategy. No generally accepted framework existed, however, for describing information age strategies. The financial framework worked well when competitive strategies were based on acquiring and managing tangible assets. In today’s knowledge economy, sustainable value is created from developing intangible assets, such as the skills and knowledge of the workforce, the information technology that supports the workforce and links the firm to its customers and suppliers, and the organizational climate that encourages innovation, problem-solving, and improvement. Each of these intangible assets can contribute to value creation. But several factors prevent the financial measurements—used in traditional, industrial age, management control systems—from measuring these assets and linking them to value creation.

- Value Is Indirect. Intangible assets such as knowledge and technology seldom have a direct impact on the financial outcomes of revenue and profit. Improvements in intangible assets affect financial outcomes through chains of cause-and-effect relationships involving two or three intermediate stages. For example:

Investments in employee training lead to improvements in service quality

Better service quality leads to higher customer satisfaction

Higher customer satisfaction leads to increased customer loyalty

Increased customer loyalty generates increased revenues and margins

The financial outcomes are separated causally and temporally from improving the intangible assets. The complex linkages make it difficult if not impossible to place a financial value on an asset such as “workforce capabilities.”

2. Value Is Contextual. The values of intangible assets depend on organizational context and strategy. They cannot be valued separately from the organizational processes that transform them into customer and financial outcomes. For example, a senior investment banker in a firm such as Goldman Sachs has immensely valuable capabilities for developing and managing customer relationships. That same person, with the same skills and experience, would be worth little to a company, such as E*TRADE.com, that emphasizes operational efficiency, low cost, and technology-based trading. The value of most intangible assets depends critically on the context—the organization, the strategy, the complementary assets—in which the intangible assets are deployed.

3. Value Is Potential. Tangible assets, such as raw material, land, and equipment, can be valued separately based on their historic cost—the traditional financial accounting method—or on various definitions of market value, such as replacement cost and realizable value. Industrial age companies succeeded by combining and transforming their tangible resources into products whose value exceeded their acquisition cost. Profit margins measured how much value was created beyond the costs required to acquire and transform tangible assets into finished products and services.

Companies today can measure the cost of developing their intangible assets—the training of employees, the spending on databases, the advertising to create brand awareness. But such costs are poor approximations of any realizable value created by investing in these intangible assets. Intangible assets have potential value but not market value. Organizational processes, such as design, delivery, and service, are required to transform the potential value of intangible assets into products and services that have tangible value.

4. Assets Are Bundled. Intangible assets seldom have value by themselves (brand names, which can be sold, are an exception). Generally, intangible assets must be bundled with other assets—intangible and tangible—to create value. For example, a new growth-oriented sales strategy could require new knowledge about customers, new training for sales employees, new databases, new information systems, a new organization structure, and a new incentive compensation program. Investing in just one of these capabilities, or in all of them but one, would cause the new sales strat-egy to fail. The value does not reside in any individual intangible asset. It arises from creating the entire set of assets along with a strategy that links them together.

The Balanced Scorecard provides a new framework to describe a strategy by linking intangible and tangible assets in value-creating activities. The scorecard does not attempt to “value” an organization’s intangible assets. It does measure these assets, but in units other than currency (dollars, yen, and euros). In this way, the Balanced Scorecard can use strategy maps of cause-and-effect linkages to describe how intangible assets get mobilized and combined with other assets, both intangible and tangible, to create value-creating customer value propositions and desired financial outcomes.

In Chapter 3, we develop the concept of a strategy map, a logical architecture that defines a strategy by specifying the relationships among shareholders, customers, business processes, and competencies. Strategy maps provide the foundation for building Balanced Scorecards linked to an organization’s strategy. Chapter 4 presents strategy maps and scorecards for several private sector organizations. These illustrate how a range of strategies can be represented in strategy maps. Chapter 5 provides analogous strategy scorecards for nonprofit, public sector, and health care organizations.

![]()

C H A P T E R T H R E E

Building Strategy Maps

WHEN WE FIRST FORMULATED THE BALANCED SCORECARD in the early 1990s, we built strategy scorecards from a clean sheet of paper. We let the story of the strategy emerge onto the four perspectives through executive interviews and interactive workshops. We have now analyzed the hundreds of strategy scorecards built since that time and have mapped the patterns into a framework that we call a strategy map. A strategy map for a Balanced Scorecard makes explicit the strategy’s hypotheses. Each measure of a Balanced Scorecard becomes embedded in a chain of cause-and-effect logic that connects the desired outcomes from the strategy with the drivers that will lead to the strategic outcomes. The strategy map describes the process for transforming intangible assets into tangible customer and financial outcomes. It provides executives with a framework for describing and managing strategy in a knowledge economy.

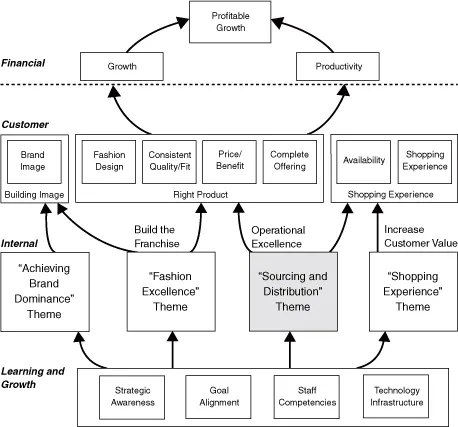

A Balanced Scorecard strategy map is a generic architecture for describing a strategy. As an example, the left-hand diagram in Figure 3-1 illustrates the architecture of a strategy map for a retail firm specializing in women’s clothing. The cause-and-effect logic of this design constitutes the hypotheses of the strategy. The financial perspective contains two themes—growth and productivity—for improving shareholder value. The value proposition in the customer perspective clearly emphasizes the importance of fashion, fit, and a complementary product line for the growth strategy. Four strategic themes in the internal perspective—brand dominance, fashion excellence, sourcing and distribution, and the shopping experience—deliver the value proposition to customers and drive the financial productivity theme. The right-hand diagram in the figure shows the detailed strategy map and Balanced Scorecard for one of the four strategic themes: sourcing and distribution. The diagram shows how this theme affects the customer objectives of product quality and product availability that, in turn, drive customer retention and revenue growth. Two internal processes—the factory management program and the line planning process—also contribute to these objectives. The former determines the quality of the factories used for manufacturing the product, and the latter determines the quantities, mix, and location. New skills and information systems support both of these processes. The strategy map and scorecard for the sourcing and distribution theme define the logic of the approach to improving product, quality, and availability. The cause-and-effect relationships on the strategy map—and the measures, targets, and initiatives on the scorecard—comprise the strategy for this theme.

Figure 3-1 A Fashion Retailer’s Strategy Map

| The Revenue Growth Strategy | The Productivity Strategy |

| “Achieve aggressive, profitable growth by increasing our share of the customer’s closet” | “Improve operating efficiency through real estate productivity and improved inventory management” |

Strategy maps help organizations see their strategies in a cohesive, integrated, and systematic way. Executives often describe the outcome from constructing this framework as “the best understanding of strategy we have ever had.” And beyond just understanding, strategy maps provide the foundation for the management system for implementing strategy effectively and rapidly.

The...