![]()

PART ONE

LAYING THE

FOUNDATION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

HOW THE KONG

RIDE LED TO

PROJECT

MANAGEMENT

FOR PROFIT

In the beginning were Arrow, two engineers named Joe, and the Kong ride.

Arrow was Arrow Dynamics, formerly Arrow Development and then Arrow-Huss, a company with a storied history and a propensity for running out of money. Based near Salt Lake City, Arrow made roller coasters. Its specialty was big, fancy rides, for the likes of Disneyland, Six Flags, and Knott’s Berry Farm. (Walt Disney himself had been a part owner of the company at one point.) Arrow was one of the most respected names in the industry, responsible for many roller-coaster innovations that are widely used today. People throughout the amusement park world knew that an innovative Arrow ride was always a big moneymaker.

The company, unfortunately, was not a big moneymaker. Its business model was to secure five or six contracts each year, build the rides, and see how much money was left at year-end. Sometimes there were profits; more often red ink. The business weathered two bankruptcies and changed hands three times during the 1980s. It was constantly scrambling to get the next contract so it could stay alive. Everyone was profiting from Arrow’s rides, it seemed, except Arrow itself. (Arrow’s final bankruptcy would come in 2001, when its assets were sold to a competitor.)

In the early 1990s, two talented young engineers came to work at Arrow.

Joe Cornwell was a mechanical engineer, born in 1959, a graduate of Christian Brothers University. At six feet seven and 280 pounds, Cornwell was a man who stood out in a crowd. He had a dark sense of humor, often coming out with phrases such as, “The best thing about people is that they are biodegradable.” At the same time, he had an unusual ability to get along with nearly everyone he met. At work, he favored T-shirts and cargo shorts. In his off-hours he enjoyed riding dirt bikes.

Joe VanDenBerghe was an electrical engineer. VanDenBerghe was closer to average height and weight, and he wore a mustache. Born in 1961, he grew up in southern Utah and earned his engineering degree from Utah State University. VanDenBerghe held a pilot’s license and later would own his own plane. He liked to tell funny stories, but his coworkers felt that he suffered from poor comic timing. It usually took them a minute to get the joke.

The pair met at Arrow and hit it off right away, working together on several projects. They discovered that they shared a taste for technical engineering challenges. They shared a distaste for Arrow’s style of management.

At one point, Cornwell and VanDenBerghe found themselves assigned to the most complex ride Arrow had ever tackled. Cornwell was the project engineer. VanDenBerghe was the lead engineer for electrical and controls. The ride would be known as Kong. At its heart was a 30-foot-tall King Kong robotic figure that interacted with theme park patrons, including giving them a dose of his banana breath. The ride part of the project was a tram car that carried people past the giant ape. As it passed, Kong would grab the tram, shake it, and then drop it toward the ground. The tram’s complex mechanisms rocked the vehicle during the shaking episode and then simulated a free fall when Kong dropped it. The mechanism stopped the tram gently as it approached the ground.

The company had assembled an all-star team to build the ride, and Cornwell and VanDenBerghe were happy to be a part of it. The technical challenges were immense—just what they liked. They watched the project clear one daunting technical hurdle after another.

But the celebrations after each accomplishment were notably short-lived. Managers began accosting the team with financial and scheduling demands. Team members began to fear that, in the grand Arrow tradition, the project was losing money. Every so often, they achieved a milestone that triggered a payment, and an accounting report would eventually show a profit or loss—usually a loss—for that portion of the project. By the time the report came out, however, the project was already two or three milestones further along. On some Arrow projects, the entire project was completed months before any accounting reports were received.

The accounting—and the lectures from management about tightening up and moving faster—smacked of Monday-morning quarterbacking. None seemed to help the project succeed. And indeed, how could they? The discussions of progress and the accounting figures often revealed worthwhile information, but by then it was mostly irrelevant. If team members had known more of the information while doing that part of the job, it would have been more useful. Instead, the team got a postgame report from the accounting department.

Cornwell and VanDenBerghe began talking intently about the situation. Wouldn’t it be nice, they asked one another, to know that your army was running low on ammunition during the battle, as opposed to learning afterward that it had run out of ammo in the middle? Wouldn’t it be good to make course corrections during a sailing voyage, rather than waiting to reach land and then figuring out where you wound up?

Arrow’s all-star team eventually completed the Kong ride. It was one of a kind, another technical marvel that would last for years. (Installed at Universal Studios in Florida, it has since been replaced by a Revenge of the Mummy ride.) True to form, the buyer made millions on the ride. Arrow lost millions in building it. Cornwell and VanDenBerghe figured there had to be a better way.

Searching for a New System

Their frustration growing, Cornwell and VanDenBerghe decided to undertake some engineering projects on their own. The automotive air bag industry was growing rapidly at the time, and one of the major companies in the business was located nearby. The two engineers worked their contacts to secure a few design-and-build contracts for automation modules to be used in air bag manufacture. Resigning from Arrow, they began to devote full time to building a new company, which they christened Setpoint.

Setpoint thrived from the beginning. Several of Cornwell and VanDenBerghe’s colleagues from Arrow joined them. More contracts came the company’s way. The small group moved from the garage that was Setpoint’s birthplace into a rented building that provided both workshop and office space. Before long Cornwell and VanDenBerghe had regular revenue, schedules to meet, and budgets to balance.

Before long, too, they were taking on another former colleague from Arrow—one of this book’s authors, Joe Knight. Knight wasn’t an engineer. He held an MBA in finance from the University of California at Berkeley, and he had worked for Ford Motor Company and several other firms. But he seemed to have the right first name. Quickly, the trio became known to their colleagues as the Joes. In 2001, Inc. magazine ran a feature article on Setpoint by editor at large Bo Burlingham. “Other companies have senior managers,” Burlingham wrote. “Setpoint has ‘the Joes.’”

From the beginning, each Joe had his own role to play. Cornwell was the visionary, the dreamer, regularly coming up with bold ideas designed to establish the company firmly in the custom automation business. He was also the social linchpin of the group, constantly using his network of contacts to find more business. VanDenBerghe was the consummate engineer, establishing and continually refining Setpoint’s internal systems, tools, and methodologies. VanDenBerghe didn’t like gray areas. If he could make everything as black-and-white as possible, he believed, the company’s decisions would be more scientific and thus more accurate. Knight, for his part, brought the financial knowledge and business experience that the others lacked.

Despite their success in launching the company, the Joes were worried. Like Arrow, Setpoint was a project-based business. And projects, they knew from their experience, were always iffy. Setpoint had to be run differently. Nobody wanted another Kong-type project.

Some changes were obvious. Arrow, constantly short of cash, was perennially late in paying its suppliers. Some of those suppliers quit doing business with the company. Others required cash up front before they would ship. One result of Arrow’s shaky relationships with vendors was periodic interruptions in the supply of parts and services. That played havoc with project schedules. Another result: inflated costs. Vendors priced their wares high, hoping to get back some of what they had lost on earlier Arrow jobs. Customers, meanwhile, sensed Arrow’s desperate need for cash and used it against the company in price negotiations.

Setpoint, the Joes determined, would always pay its bills on time. And it would cultivate close working relationships with customers.

Solving the basic problem of projects, however, was more challenging. For instance, the Joes asked themselves this:

What would be required for us to know what a project was really going to cost? Wouldn’t it be great if we could see real costs in detail as the project goes along? The purpose of a business, after all, is to make money, and if we don’t know our costs, we won’t have a clue regarding our profit.

And this:

What about knowing as we went along how long the project was really going to take? And whether it would really meet the customer’s specifications without a lot of change orders or budget overruns? Wouldn’t that be great, too?

Project managers, they felt, lived in a world of unreality, held together by hope and prayer. What would it take to bring projects into the real world, to create a sense of commitment and discipline among everyone involved, to keep everyone focused on the right priorities?

Maybe, they decided, we could design a project management system that would do all that. We’re engineers, aren’t we? And that’s what engineers do: design systems.

The design specs for this system would include all that real-time knowledge just mentioned. They would also include several other requirements for successful projects:

- The system would be proactive rather than reactive. It would allow a project team to get on top of what needed to be done, rather than continually putting out fires.

- The system would help project teams achieve both short-term and long-term goals, and it would tie financial scorekeeping directly to those goals. It would enable the company to reward people for hitting accurately determined project targets.

- It would allow for regular, accurate communication with customers, in words they could understand.

- It would build in commitment and discipline from top to bottom, overcoming the complacency that often shows up in the early stages of a long job.

- Finally, it would help people focus on tasks that were important rather than urgent.

That last requirement may require a word of explanation, because project managers and team members are forever concentrating on whatever seems most urgent. That practice, the Joes believed, was exactly wrong, and was at the heart of a lot of project management troubles.

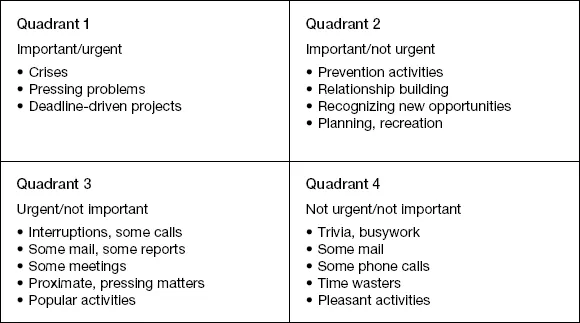

Stephen R. Covey’s famous time management system divides tasks into the two-by-two matrix shown in figure 1-1. In his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Covey argues that all critical work is completed in quadrant 2, the one labeled Important/not urgent. The Joes believed that every project management activity, when properly executed, should fall into quadrant 2. Their reasoning was simplicity itself. Every project management activity is important, or else it shouldn’t be done at all. And every task should be completed before it becomes urgent. If a task is suddenly urgent, it is likely to be expensive—and the project manager has failed.

FIGURE 1-1

The Covey time management matrix

Source: Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (New York: Free Press, 2004), 151.

Now that they had their design specs formulated, it was time for the real work to begin. The ambitious specifications had to be rolled together into a workable business system that everyone could easily understand and use. Of course, it also had to integrate directly, in real time, with Setpoint’s accounting system. Little did they know how big that factor would become.

To understand it, we’ll have to take a brief detour into the world of accounting.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

WHY THE

ACCOUNTING

DEPARTMENT IS

YOUR WORST

ENEMY

In the United States, a mammoth code known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP, pronounced “gap”) spells out the procedures governing accounting. GAAP comprises thousands of pages’ worth of rules and guidelines. A private organization called the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) monitors GAAP and regularly updates it. Most other countries have something similar.

Every publicly traded company in the United States must maintain its books according to the rules of GAAP. Privately held companies aren’t required to do so, but if a private company wants to establish a credit line or get a loan from a bank, it will often have to show the bank’s loan officer a set of financial statements compiled or audited according to GAAP. When Joe Cornwell and Joe VanDenBerghe started Setpoint, they hired a certified public accountant to set up the company’s books. Like any self-respecting CPA, he followed GAAP’s rules in doing so.

Cornwell, trained as a mechanical engineer, didn’t know accounting. But he decided he would learn. He talked to the accountant. He bought some textbooks. Then he began meeting every Wednesday night with his friend Joe Knight, the finance expert, who at that point hadn’t yet joined Setpoint. They got together at the small building that served as Setpoint’s combined office and shop.

Cornwell also wanted to share some financial data with his employees. The group at ...