![]()

PART I

The Three-Dimensional Developmental Model

THE FIRST THREE chapters of this book present the three developmental dimensions that make up our model: ownership, family, and business. Each chapter explores the stages of one dimension in detail, providing the theoretical and conceptual foundation for our generalizations and conclusions about family business. In particular, we focus on the key challenges of each stage, which must be met as the system continues to develop.

![]()

1

The Ownership Developmental Dimension

EVEN MORE THAN the family name on the door or the number of relatives in top management, it is family ownership that defines the family business. Just as for family and business structure, there are many forms that ownership may take in the family business. The structure and distribution of ownership—who owns how much of what kind of stock—can have profound effects on other business and family decisions (who will be CEO or a family leader, for instance) and on many aspects of operations and strategy. In fact, we have observed that even minor structural changes in ownership, whether triggered by the aging of family members or by strategic decisions, can have powerful ripple effects through each of the three circles for generations. These different patterns of ownership, evolving over time, make up the first developmental dimension of this model.

Private ownership of enterprise has been a hot topic for many centuries. Aristotle’s Politics and Plato’s Laws and Republic had much to say about the role of private ownership in the creation of the ideal state.1 Debates over inheritance laws and customs have been well documented in the cultural history of societies as varied as medieval Europe, ancient China, and the colonial Americas.2 One central premise of the Communist Manifesto was the abolition of private ownership and inheritance (especially of work enterprises).3 At the same time, capitalist economies were witnessing the dramatic expansion of the business-owning middle class and the introduction of public shareholding. Even theology has addressed private enterprise, as in the Papal Encyclical of 1891, which found divine justification for the family’s right to “the ownership of profitable property” and its “transmission to children by inheritance.”4

Even so, early work in the family business field gave less attention to ownership than to either management or family dynamics. Recently, however, some of the best research on family firms has been on their governance and ownership dynamics. The three-circle model explicitly identified the ownership group in the family business system, replacing the two-circle concept that did not differentiate between ownership and management.5 Then the insightful work of John Ward first called attention to different categories of ownership for family companies.6 Ward proposed a typical progression of ownership from founder to sibling partnership, and finally to the family dynasty. Our own thinking about how the ownership structure develops in a family company, and how ownership influences the dynamics of the entire system, has been strongly influenced by Ward’s work.

There has been a tendency to see ownership as simply passed from one generation to another as a by-product of management control. Actually, an accurate and detailed portrayal of the range of family businesses reveals a much broader and more interesting variety of ownership structures. Ownership can be held through different classes of stock, in an infinite variety of trusts, and by elaborate multigenerational combinations of large and small distributions. Furthermore, these shareholding configurations are typically the prime determining characteristic of the stage of development of the family company.

Thinking Developmentally about Ownership

The structure of ownership in a family business can remain static for generations, even as the individual owners change. For example, a winery outside Lausanne, Switzerland, has placed majority control in the hands of one family member in each generation for fourteen generations—a sequence of single dominant owners for over 300 years. Typically, however, after the first generation, the form of ownership, not just the individual owners, changes between generations. Most often, ownership becomes increasingly diluted from a single majority owner, to a few or several owners, and then on to a much broader distribution. With each change in the ownership structure, there are corresponding changes in the dynamics of the business and the family, the level of power held by employed and nonemployed shareholders, and the financial demands placed on the business.

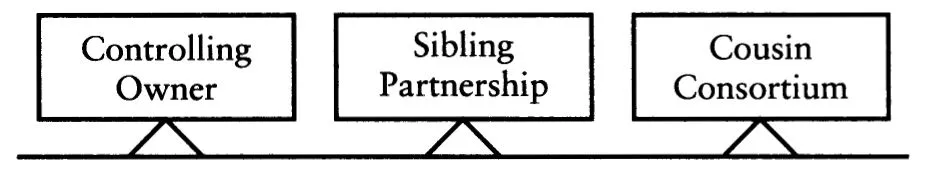

Figure 1-1 ■ The Ownership Developmental Dimension

Although the specific ownership structure in any family company reflects its unique history and family membership, most cases fall into one of three types (figure 1-1): companies controlled by single owners (Controlling Owner), by siblings (Sibling Partnership), and by a group of cousins (Cousin Consortium).7 We think of the progression of ownership from one form to another as developmental because it follows a predictable sequence and is at least partially driven by the aging and expansion of the owning family. However, this is a loose interpretation of the concept of development. The sequence of stages is not inalterably determined along a fixed path, as is much of biological development. And companies may be founded with any of the three ownership forms. As in the Swiss winery, ownership of the family business may remain concentrated in one or a few persons for many generations. Alternatively, the distribution of shares can move back and forth among individual, sibling, and cousin control, following periods of consolidation, expansion, and transfer of ownership both within and between generations.

The Ownership Stages of the Family Business

In the United States and most other Western economies, we estimate that about 75 percent of all family companies are majority owned by one person or by a married couple; we categorize them as Controlling Owner family companies. Around 20 percent of all U.S. family companies are ownership controlled by Sibling Partnerships. Finally, we estimate that around 5 percent of family companies are Cousin Consortiums.8

Many family companies have hybrid ownership forms;9 for instance, majority controlled by one group of siblings but with some cousin shareholders as well, and perhaps even managed by the minority cousin owners. These hybrids normally represent transitions from one stage to another. Especially in later generations, the range of siblings’ and cousins’ ages can be broad and the generations can become mixed. Therefore it is very common for ownership to change from one stage to another in a series of intermediate steps that may last from a few months to many years.

The Controlling Owner Stage

Characteristics

Most, but not all, family businesses are founded as Controlling Owner companies, in which ownership is controlled by one owner or, less typically, a married couple.10 It is tempting to label these companies “entrepreneurial” family businesses, because most founder businesses are of this form, but that would be somewhat inaccurate. Not all Controlling Owner family businesses are entrepreneurial (in the sense of being innovative or risk taking), and not all entrepreneurial businesses have one controlling owner.

The Controlling Owner Stage of Ownership Development

Characteristics

- ■ Ownership control consolidated in one individual or couple

- ■ Other owners, if any, have only token holdings and do not exercise significant ownership authority

Key Challenges

- ■ Capitalization

- ■ Balancing unitary control with input from key stakeholders

- ■ Choosing an ownership structure for the next generation

Controlling Owner family businesses vary enormously in size. Although most remain modest in scale, some achieve revenues of many millions of dollars, sometimes even within the first generation. Family employees are most often limited to the nuclear family of the owner. The board of directors, especially in the first generation of an owner-manager family business, is typically a “paper board,” which exists only to meet incorporation requirements but performs no real advisory role, or a “rubber stamp board,” which meets only to endorse what the owner-manager has already decided to do. In both cases, these boards tend to be composed entirely or primarily of family members. Because of the owner-manager’s dominant position in the company and often in the family, board meetings are generally not forums for business or family debate.

Cragston Employment Services

A powerful illustration of the importance of ownership factors at the Controlling Owner stage is provided by Cragston, an impressive service business that has grown to over $100 million in sales in its first generation. In 1978 Arthur Cragston, the charismatic and visionary founder, bought a small firm that processed workers’ compensation claims. Arthur had just earned a degree from a local law school. Since he was already thirty-six, with a family to support, he was pessimistic about his chances to rise quickly enough in the hierarchy of a major law firm. When he learned that the father of a law school acquaintance was trying to sell a small company that processed workers’ compensation claims, he put together his modest savings and went to a local bank to borrow the rest of the purchase price. The bank turned him down, citing his lack of business experience. But Arthur was determined. He remortgaged his home and convinced the company’s seller to finance the rest of the purchase with a 10-year note. The office came with two full-time and two part-time employees. Arthur’s second wife, Carolyn, helped him run the office for a few years, then returned to her vocation as a novelist.

The firm was modestly successful for two years, until Arthur began to read about a new trend toward contract employees. Craig, a longtime friend who was a CPA, came to Arthur with an idea to transform Arthur’s company. They would serve medium-sized companies by “hiring” all their employees for them, handling all benefit and tax matters, and leasing the staff back to the employer. Craig proposed a partnership, but Arthur offered a generous salary and profit share instead. Craig contributed a small amount of investment capital from his savings in return for a 10 percent share of the stock, and the deal was made. Arthur and Craig put together a packet of sales materials and began to make the rounds of Arthur’s current workers’ compensation clients, pitching the new arrangement. Only two were interested, but it gave the new company, Cragston Employment Services, the experience it needed. Just after the first six months with these first two clients, two very favorable rulings came down from the IRS, in support of the employee leasing concept. Suddenly, demand exploded; Cragston was riding a huge new wave and began to grow rapidly.

To save on initial operating costs, Arthur continued to run Cragston out of the tiny office that he had used for his workers’ compensation employees. He hired new staff one by one as he needed them, stretching current staff near the breaking point with long hours and overtime until it was essential to add a new person. His personal style with each employee and his stories about the great company they were building worked amazingly well to motivate the staff.

One day, at a business lunch, Arthur met Frank Hampton, who was also developing an employee leasing program for a large employment services company. Arthur decided he needed Frank’s expertise at Cragston and offered him a 50 percent raise over his current salary and generous performance incentives to come to work for him. When Craig heard about the offer, he was furious. After a bitter and near-violent fight, Arthur fired Craig. Craig filed suit and, with Arthur refusing to settle out of court, the battle dragged on for almost three years, eventually costing the company thousands of dollars.

Frank took over management of the individual client plans, while Arthur handled marketing. The office was in constant turmoil because of the frantic level of activity in the cramped space. Arthur was a gifted salesman, and he was rapidly generating business. Frank often complained that he could not keep up without new staff, better computers, and more room. Arthur’s first response was always, “If the customers don’t see it, we can’t afford to spend money on it.” The real problem was that Arthur still insisted on knowing every part of each customer’s package. Each new proposal required Arthur’s approval at every step. Since he was also out in the field selling new accounts, paperwork piled up on his desk. Frank finally convinced Arthur to hire a new accountant to get the books in order and take a look at their cash flow. As a result of this work, it became clear that the business could afford higher rent and more staff out of current operating revenues, avoiding the kind of debt that Arthur feared. Following the move to a larger, better equipped office, things calmed down, and Arthur took a week’s vacation with his family—his first time away from the company in three years.

Key Challenges

Three key challenges characterize the Controlling Owner stage: securing adequate capital, dealing with the consequences of ownership concentration, and devising an ownership structure for continuity. Arthur Cragston succeeded because he responded well to the first of these challenges and survived his problems with the second one. However, as shown later, his avoidance of the continuity issue may mean that the business never moves beyond the Controlling Owner stage.

Capitalization. In first-generation firms, where the owner-manager is the founder, the principal sources of capital are usually the savings and “sweat equity” invested by the majority owner, family, and friends. Unless the individual owner-manager has considerable investment capital, first-generation firms usually pool assets from family members. Although there may be important psychological strings attached, these are still the most unencumbered sources: the spouse (investing either his or her own funds or assets inherited from the in-law family), parents, siblings, or even children of the owner-manager. Relatives are more likely than outsiders to loan money to the founder with only the promise of dividends and asset appreciation if the business succeeds, and without any intention to help run the company. Sometimes there is a family norm of putting excess cash into relatives’ new ventures. Sometimes new spouses have savings, in the family business v...