![]()

1

WHAT IT MEANS TO PUT

ANALYTICS TO WORK

IF WE WANT TO MAKE better decisions and take the right actions, we have to use analytics. Putting analytics to work is about improving performance in key business domains using data and analysis. For too long, managers have relied on their intuition or their “golden gut” to make decisions. For too long, important calls have been based not on data, but on the experience and unaided judgment of the decision maker. Our research suggests that 40 percent of major decisions are based not on facts, but on the manager’s gut. 1

Sometimes intuitive and experience-based decisions work out well, but often they either go astray or end in disaster: executives pursue mergers and acquisitions to palliate their egos, neglecting the sober considerations that create real value; banks make credit and risk decisions based on unexamined assumptions about always-rising asset values; governments rely on sparse intelligence before deciding whether to wage war. Such are the most extreme cases of ill-informed decision making.

In other cases, nonanalytical decisions don’t lead to tragedy, but they do leave money on the table: businesses price products and services based on their hunches about what the market will bear, not on actual data detailing what consumers have been willing to pay under similar circumstances in the past; managers hire people based on intuition, not on an analysis of the skills and personality traits that predict an employee’s high performance; supply chain managers maintain a comfortable level of inventory, rather than a data-determined optimal level; baseball scouts zoom in on players who “look the part,” not on those with the skills that—according to analytics—win games.

Socrates said, “The unexamined life isn’t worth living.” We’d argue that “the unexamined decision isn’t worth making.”

Consider this firsthand report from an executive with a software company. When asked about a recent sales seminar put on by the firm, he replied: “It went fine. We had attendees from 110 companies who received a keynote presentation designed to instill confidence in our company’s future and to encourage cross-selling, and all twelve technical sessions were well received.”

That would be enough for many companies. “I guess no decision needs to be made other than to continue holding these seminars at a pace of twelve per quarter around the country,” he reflected. But after further thought, he voiced some disquieting questions about what the sales seminar did not reveal:

• How many attendees were existing customers and how many were prospects?

• Were there attendees from every customer within the geographic area?

• Were there attendees from every prospect in the geographic area?

• Which attendees were high-growth prospects?

• How many attendees also attended the company’s annual conference?

His company simply didn’t know the answers to these questions. It had never bothered to gather and analyze the data. The executive considers his company to be more analytical than most, but, at least with regard to these seminars, it has a long way to go. As this anecdote suggests, even relatively smart and sophisticated companies are missing opportunities to put analytics to work and thereby profit from better decisions.

Companies that continue to manage on autopilot—by having sales seminars because that’s what’s always been done, for example—are not competing as effectively as they could be. In this book, we’ll provide you with a set of tools to make your organization more analytical. We’ll demonstrate that becoming more analytical is not solely the responsibility of a manager: it’s an essential concern for the entire organization.

What’s the payoff for putting analytics to work in your organization? There are many, as shown in “Some Benefits of Being Analytical.” We believe it’s no accident that the companies we cite as outstanding analytical competitors are often also outstanding performers. Analytics aren’t the only way an organization can succeed, but in most industries there are excellent illustrations that the analytical path is a viable route to success.

Some Benefits of Being Analytical

• Help manage and steer the business in turbulent times. Analytics give managers tools to understand the dynamics of their business, including how economic and marketplace shifts influence business performance.

• Know what’s really working. Rigorous analytical testing can establish whether your intervention is causing desired changes in your business, or whether it’s simply the result of random statistical fluctuations.

• Leverage previous investments in IT and information to get more insight, faster execution, and more business value in many business processes.

• Cut costs and improve efficiency. Optimization techniques can minimize asset requirements, and predictive models can anticipate market shifts and enable companies to move quickly to slash costs and eliminate waste.

• Manage risk. Greater regulatory oversight will require more precise metrics and risk management models.

• Anticipate changes in market conditions. You can detect patterns in the vast amount of customer and market data coming your way.

• Have a basis for improving decisions over time. If you are using clear logic and explicit supporting data to make a decision, you or someone else can examine the decision process more easily and try to improve it.

What Do We Mean by “Analytical”?

By analytical we mean the use of analysis, data, and systematic reasoning to make decisions. What kind of analysis? What kind of data? What kind of reasoning? There are no hard-and-fast answers; we contend that almost any analytical process can be good if provided in a serious, systematic fashion.

Many approaches to analysis are fair game, from the latest optimization techniques to tried-and-true versions of root-cause analysis. Perhaps the most common is statistical analysis, in which data are used to make inferences about a population from a sample. Variations of statistical analysis can be used for a huge variety of decisions—from knowing whether something that happened in the past was a result of your intervention, to predicting what may happen in the future. Statistical analysis can be powerful, but it’s often complex, and sometimes employs untenable assumptions about the data and the business environment.

When done correctly, statistical analyses can be both simple and valuable. You may remember from your college statistics course that “measures of central tendency”—means, medians, and modes (everybody always forgets what a mode is; it’s simply the category with the highest frequency)—are useful ways to express what’s going on in data. Sometimes analysis simply means a visual exploration of data in graphic form. You can look at a series of points on a two-dimensional graph, for example, and notice a pattern or relationship. Are there outliers in a pattern that require explanation? Are some values out of range? Visual analysis helps us to “stay close to the data” using “exploratory data analysis,” an approach that the great statistician John Tukey made respectable and Edward Tufte further popularized by helping people create clear visual representations of their data. 2

The key is to always be thinking about how to become more analytical and fact based in your decision making and to use the appropriate level of analysis for the decision at hand—and when analyses and decisions are working well, not to rest on your laurels, lest you get stuck in a decision-making rut and be unable to adapt quickly when conditions change.

Some areas of business, like environmental sustainability, haven’t historically used data or analysis, so you could become more analytical by creating simple metrics of key activities (for example, a carbon footprint), reporting them on a regular basis, and acting on the patterns that emerge. This initial step would accomplish a lot—but getting an organization to agree upon metrics in a new area is no easy task.

In other areas, such as customer behavior, you may have so much detailed data available—from a loyalty card program, say, or a Web site—that making good decisions about how to treat customers requires sophisticated analytics, including detailed segmentation, scoring customers based on their propensity to exhibit certain behaviors, and next-best-offer analysis for what customers should buy next. Producing a mere report would be seriously underachieving in this data-rich domain.

Of course, some forms of analysis don’t require quantitative data. For example, in the fields of corporate anthropology and ethnography, marketers conduct analysis by systematically observing customers while they use products or shop in stores. As Yogi Berra noted, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” The most rigorous marketers employ video and systematic behavior coding to ensure that all recorded behaviors can be analyzed later in detail. Ethnography can help companies identify problems that customers have with their products and services. Data gained through observation can also shed light on a statistical association. We may know that men with young families purchase both beer and diapers in the grocery store, but only systematic observation can reveal which they buy first, and whether it makes sense to shelve them in close proximity or at opposite ends of the store.

The most analytical firms and managers employ a combination of techniques, both quantitative and qualitative. eBay, for example, undertakes extensive and varied analyses by performing randomized tests of Web page variations before making any change to the Web site or the business model. With more than a billion page views per day, eBay can run thousands of such experiments, many concurrently. To make sense of all these tests, eBay built its own application, called the eBay Experimentation Platform, to lead testers through the process and to keep track of what’s being tested at what times on what pages. Of course, you may not feel that you can undertake the kinds of complex and detailed testing and analyses that eBay, blessed with a massive amount of data (all those mouse clicks), can support.

But in addition to online testing, eBay considers changes to its Web site using a variety of analytical approaches: the company conducts extensive, face-to-face testing with its customers, including lab studies, home visits, participatory design sessions, focus groups, and iterative trade-off analysis. eBay also conducts quantitative visual design research and eye-tracking studies, and diary studies to see how users feel about potential changes. The company will make no significant changes to its site without these analyses. This analytical orientation is not the only reason eBay is successful, but it’s clearly one factor, with 113 million items for sale in over fifty thousand categories at any given time.

It’s not our goal in this book to provide you with a list of all possible analytical tools, but rather to persuade you that putting analytics to work can help your managers and employees make better decisions, and help your organization perform better. Analytics aren’t just a way of looking at a particular problem, but rather an organizational capability that can be measured and improved. It is our goal to describe the primary components of that capability and the best ways to strengthen them. Think of this book as therapy for your organization’s analytical brain.

What Kinds of Questions Can Analytics Answer?

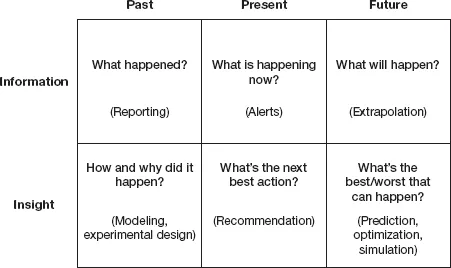

Every organization needs to answer some fundamental questions about its business. Taking an analytical approach begins with anticipating how information will be used to address common questions (see figure 1-1). These questions are organized across two dimensions:

• Time frame. Are we looking at the past, present, or future?

• Innovation. Are we working with known information or gaining new insight?

The matrix in figure 1-1 identifies the six key questions that data and analytics can address in organizations. The first set of challenges is using information more effectively. The “past” information cell is the realm of traditional business reporting, rather than analytics. By applying rules of thumb, you can generate alerts about the present—what’s happening right now (like whenever an activity strays outside of its normal performance pattern). Using simple extrapolation of past patterns creates information about the future, such as forecasts. All of these questions are useful to answer, but they don’t tell you why something happens or how likely it is to recur.

The second set of questions requires different tools to dig deeper and produce new insights. Insight into the past is gained by statistical modeling activities, which explain how and why things happened. Insight into the present takes the form of recommendations about what to do right now—for example, what additional product offering might interest a customer. Insight into the future comes from prediction, optimization, and simulation techniques to create the best possible future results.

FIGURE 1-1

Key questions addressed by analytics

Together these questions encompass much of what an organization needs to know about itself. The matrix can also be used to challenge existing uses of information. You may find, for example, that many of your “business intelligence” activities are in the top row. Moving from purely information-oriented questions to those involving insights is likely to give you a much better understanding of the dynamics of your business operations.

Analytics for the Rest of Us

In our...