- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work (HBR Guide Series)

About this book

Are you suffering from work-related stress?

Feeling overwhelmed, exhausted, and short-tempered at work—and at home? Then you may have too much stress in your life. Stress is a serious problem that impacts not only your mental and physical health, but also your loved ones and your organization. So what can you do to address it?

The HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work will help you find a sustainable solution. It will help you reach the goal of getting on an even keel—and staying there. You'll learn how to:

- Harness stress so it spurs, not hinders, productivity

- Create realistic and manageable routines

- Aim for progress, not perfection

- Make the case for a flexible schedule

- Ease the physical tension of spending too much time at your computer

- Renew yourself physically, mentally, and emotionally

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work (HBR Guide Series) by Harvard Business Review in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Crescita personale & Competenze per il business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

Understanding How You’re Wired

Chapter 1

Are You Working Too Hard?

A Conversation with Herbert Benson, MD

A summary of the full-length HBR interview with Herbert Benson, MD, highlighting key ideas.

THE IDEA IN BRIEF

The key to overcoming negative stressors is the breakout principle, or relaxing at the height of your struggle. There are four steps:

- Take on a thorny problem, and really work hard at it until you feel you have reached the limits of your performance.

- Walk away. Do something entirely different, such as breathing deeply while focusing on a calm phrase or taking a nap or hot shower.

- Let go. This is the actual breakout, where you experience a flow of creative ideas and solutions.

- Return to the “new-normal” sense of self-confidence.

Do the breakout sequence whenever you need to—and achieve gains in productivity and success.

When does stress help your performance, and when does it hurt? To find out, HBR senior editor Bronwyn Fryer talked with Herbert Benson, MD, founder of the Mind/Body Medical Institute in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Also an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Benson has spent more than 35 years conducting research in the fields of neuroscience and stress. He is best known for his 1975 best-seller, The Relaxation Response. He first described a technique to bring forth the complex physiological dance between stress and relaxation, and the benefits to managers of practices such as meditation, in “Your Innate Asset for Combating Stress” (HBR July–August 1974). His most recent book is Relaxation Revolution (Scribner, 2011) with William Proctor.

Benson and Proctor have found that we can learn to use stress productively by applying the breakout principle—a paradoxical active-passive dynamic. By using simple techniques to regulate the amounts of stress we feel, we can increase performance and productivity and avoid burnout. In this edited conversation, Benson describes how we can tap into our own creative insights, boost our productivity at work, and help our teams do the same. He is quick to acknowledge the large part Proctor’s thinking has played in the ideas he discusses here.

HBR: We all know that unmanaged stress can be destructive. But are there positive sides to stress as well?

Yes, but let’s define what stress is first. Stress is a physiological response to any change, whether good or bad, that alerts the adaptive fight-or-flight response in the brain and the body. Good stress, also called eustress, gives us energy and motivates us to strive and produce. We see eustress in elite athletes, creative artists, and all kinds of high achievers. Anyone who’s clinched an important deal or had a good performance review, for example, enjoys the benefits of eustress, such as clear thinking, focus, and creative insight.

But when most people talk about stress, they are referring to the bad kind. At work, negative stressors are usually the perceived actions of customers, clients, bosses, colleagues, and employees, combined with demanding deadlines. At the Mind/Body Medical Institute, we also encounter executives who worry incessantly about . . . the impact of China on their companies’ markets, the state of the economy, the world oil supply, and so on. Additionally, people bring to work the stress aroused by dealing with family problems, taxes, and traffic jams, as well as anxieties stemming from a continuous diet of bad news that upsets them and makes them feel helpless—hurricanes, politics, child abductions, wars, terrorist attacks, environmental devastation, you name it.

Many companies offer various kinds of stress-reduction programs, from on-site yoga classes and massage to fancy gyms to workshops. What’s wrong with these?

It’s critical that companies do something to address the rampant negative effects of workplace stress if they want to compete effectively, but often the kinds of programs they institute are stopgaps. HR may bring in a lecturer once or twice a year or set up tai chi sessions and urge everyone to go, but few people show up because they feel they can’t take the time to eat their lunch, much less spend an hour doing something perceived as both unrelated to work and relaxing to boot. Unless the leadership and culture explicitly encourage people to join in, employees will continue to feel guilty or worry that they’ll be seen as slackers if they go.

This state of affairs is inexcusable if you look at the billions lost to absenteeism, turnover, disability, insurance costs, workplace accidents, violence, workers’ compensation, and lawsuits, not to mention the expense of replacing valuable employees lost to stress-related problems. Fortunately, each of us holds the key for managing stress, and leaders who learn to do this and help their employees to do likewise can tap into enormous productivity and potential while mitigating these costs.

What is the science behind your research, and what does it reveal?

First, let me say that we at the Mind/Body Medical Institute didn’t discover anything new. The American philosopher William James identified the breakout principle in his Varieties of Religious Experience in 1902. What we set about to do was explore the science behind what James had identified.

Over the past [several decades], our teams have collected data on thousands of subjects from population studies, physiologic measurements, brain imaging, molecular biology, biochemistry, and other approaches to measuring bodily reactions to stress. From these we identified the relaxation response and could see how powerful it was. It is a physical state of deep rest that counteracts the harmful effects of the fight-or-flight response, such as increased heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension.

Neurologically, what happens is this: When we encounter a stressor at work—a difficult employee, a tough negotiation, a tight deadline, or worse—we can deal with it for a little while before the negative effects set in. But if we are exposed for excessively long periods to the fight-or-flight response, the pressure on us will become too great, and our system will be flooded with the hormones epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. These cause blood pressure to rise and the heart rate and brain activity to increase, effects that are very deleterious over time. But our . . . findings indicate that by completely letting go of a problem at that point by applying certain triggers, the brain actually rearranges itself so that the hemispheres communicate better. Then the brain is better able to solve the problem.

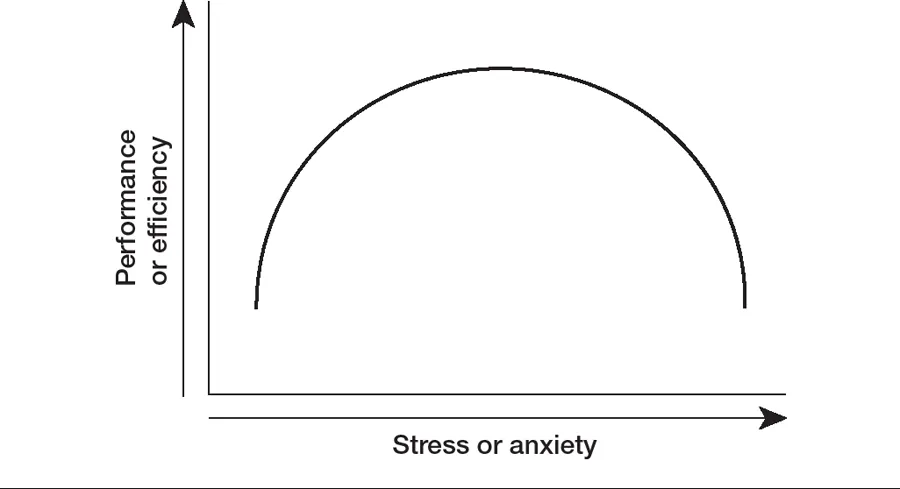

The best way to understand this mechanism is to go back [about] 100 years to the work of two Harvard researchers, Robert Yerkes and John Dodson. In 1908, these two demonstrated that efficiency increases when stress increases, but only up to a point; after that, performance falls off dramatically (see figure 1-1). We found that by taking the stress level up to the top of the bell curve and then effectively pulling the rug out from under it by turning to a quieting, rejuvenating activity, subjects could evoke the relaxation response, which effectively counteracts the negative effects of the stress hormones. Molecular studies have shown that the calming response releases little “puffs” of nitric oxide, which has been linked to the production of such neurotransmitters as endorphins and dopamine. These chemicals enhance general feelings of well-being. As the brain quiets down, another phenomenon that we call calm commotion—or a focused increase in activity—takes place in the areas of the brain associated with attention, space-time concepts, and decision making.

FIGURE 1-1

The Yerkes-Dodson curve

Stress is an essential response in highly competitive environments. Before a race, before an exam, before an important meeting, your heart rate goes up and so does your blood pressure. You become more focused, alert, and efficient. But past a certain level, stress compromises your performance, efficiency, and eventually your health. Two Harvard researchers, Robert M. Yerkes and John D. Dodson, first calibrated the relationship between stress and performance in 1908, which has been dubbed the Yerkes-Dodson law.

In eliciting the relaxation response, individuals experience a sudden creative insight, in which the solution to the problem becomes apparent. This is a momentary phenomenon. Thereafter, the subjects enter a state of sustained improved performance, which we call the new-normal state, because the breakthrough effect can be remembered indefinitely.

We find this to be an intriguing phenomenon. By bringing the brain to the height of activity and then suddenly moving it into a passive, relaxed state, it’s possible to stimulate much higher neurological performance than would otherwise be the case. Over time, subjects who learn to do this as a matter of course perform at consistently higher levels. The effect is particularly noticeable in athletes and creative artists, but we have also seen it among the businesspeople we work with.

So how can we actually go about tapping into the breakout principle?

A breakout sequence occurs in four steps. The first step is to struggle mightily with a thorny problem. For a businessperson, this may be concentrated problem analysis or fact gathering; it can also simply be thinking intently about a stressful situation at work—a tough employee, a performance conundrum, a budgetary difficulty. The key is to put a significant amount of preliminary hard work into the matter. Basically, you want to lean into the problem to get to the top of the Yerkes-Dodson curve.

You can tell when you have neared the top of the curve when you stop feeling productive and start feeling stressed. You may have unpleasant feelings such as anxiety, fearfulness, anger, or boredom, or you may feel like procrastinating. You may even have physical symptoms such as a headache, a knot in the stomach, or sweaty palms. At this point, it’s time to move to step two.

Step two involves walking away from the problem and doing something utterly different that produces the relaxation response. There are many ways to do this. A 10-minute relaxation-response exercise, in which you calm your mind and focus on your out-breath while disregarding the thoughts you’ve been having, works extremely well. Some people go jogging or pet a furry animal; others look at paintings they love. Some relax in a sauna or take a hot shower. Still others “sleep on it” by taking a nap or getting a good night’s rest, having a meal with friends, or listening to their favorite calming music. One male executive I know relaxes by doing needlepoint. All of these things bring about the mental rearrangement that is the foundation for new insights, solutions, and creativity. The key is to stop analyzing, surrender control, and completely detach yourself from the stress-producing thoughts. When you allow your brain to quiet down, your body releases the puffs of nitric oxide that make you feel better and make you more productive.

One executive we observed was worried about a big presentation she had to make before some top-level managers. She worked and worked on it, but the harder she worked, the more befuddled she became and the more anxiety took over. Fortunately, she had learned to evoke her relaxation response by visiting the art museum near her office. So she did. After a while, she felt a sense of total release as she stood there looking at her favorite pictures. At that point, she suddenly had the insight that she was trying to cover too many topics at once and needed to pare down the presentation to a single, overriding concept she could illustrate with solid examples. She felt inspired and confident that she had the answer. She went back to the office, redid the presentation, and, feeling relaxed and happy, went home for the day.

This third step—gaining a sudden insight—is the actual breakout. Breakouts are also often referred to as peak experiences, flow, or being in the zone. Elite athletes reach this state when they train hard and then let go and allow the muscle memory to take over. They become completely immersed in what they’re doing, which feels automatic, smooth, and effortless. In all cases, a breakout is experienced as a sense of well-being and relaxation that brings with it an unexpected insight or a higher level of performance. And it’s all the result of a simple biological mechanism that we can tap into at will.

The final step is the return to the new-normal state, in which the sense of self-confidence continues. The manager who reorganized her presentation, for example, came in the next morning knowing all would be well. The meeting did go well, and she received accolades for her work from her bosses and colleagues.

Does a breakout occur all the time or just occasionally? What percentage of people, according to your research, experience breakouts in this way?

We don’t yet have hard data on this, but anecdotally I can tell you that when you compare groups of people who have been trained to evoke the relaxation response to groups who lack such training, the former experience breakouts much more frequently. About 25% of people trained in this process, and sometimes many more, can reliably reach the breakout stage.

It sometimes takes a serious illness caused or exacerbated by stress for people to have their “aha” moments. One well-known CEO we worked with spent years putting in more than 60 hours a week at his intensely stressful job. He came to us after he had been diagnosed with a silent heart attack. His world had completely turned upside down. He took a leave of absence from work to focus on healing, to ask himself why he was on the planet, and to spend time with his family. We trained him to use the relaxation response and the breakout principle. He recovered and came back to work far more resilient and productive than he was before.

Can teams or groups do this together or somehow feed off one another?

Certainly. The benefits of mind/body management are by no means limited to individuals. Those who become skilled in these techniques can also expect to have an exponential impact in groups or teams; they can work together to solve organizational problems as part of what we might call a mind/body orchestra.

Let me give you an example of how this works. A few years ago, three software executives with whom we had worked spent two days trying to cajole venture capitalists in Singapore to fund several projects having to do wi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- What You’ll learn

- Contents

- Introduction: Nine Ways Successful People Defeat Stress

- Section 1: Understanding How You’re Wired

- Section 2: Renewing Your Energy

- Section 3: Improving Your Work/Life Balance

- Section 4: Finding The Tools That Work For You

- Index

- Back Cover