![]()

PART ONE

Creating the Corporate Theory

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Foresight, Insight, and Cross-Sight

Value creation in all domains, from product development to strategy, involves a process of creatively recombining existing elements in novel ways.1 James Burke, author of the PBS series Connections, which documents the origins of great discoveries, noted that: “ … at no time did an invention come out of thin air into somebody’s head … You just had to put a number of bits and pieces that were already there, together, in the right way.”2 Steve Jobs similarly characterized the design process as “keeping five thousand things in your brain … and fitting them all together … in new and different ways to get what you want.”3

The corporate strategist’s task is no different. It is to assemble available assets, capabilities, and activities in new ways in search of competitive advantage for the firm. But more importantly, the corporate strategist’s task is to do this successfully over and over again. This is like an almost-blind explorer navigating a rugged, mountainous landscape in constant search for a higher peak. Since she cannot clearly see the terrain, she must develop some theory of what she will find, drawing from available knowledge and past experience. Then, by conducting strategic experiments, which in the corporate world amounts to assembling assets and activities, she gains a clearer vision of some limited portion of this topography.

Strategic experiments can be costly and time-consuming. They may require several years to assemble, and often involve highly specialized and largely irreversible investments. Consequently, engaging in a purely random, experimental search for increased value is unacceptable. That’s why good strategists compose theories of how to navigate this terrain. Like a scientist’s theory, the strategist’s theory generates hypotheses that guide actions.4 Theories define expectations about causal relationships: If the world functions according to my theory, then this action will generate the following outcome. They are dynamic and are updated based on evidence or feedback received. They permit low-cost thought experiments, thereby minimizing expensive, misguided investments.

Just as academic theories enable scientists to generate breakthrough knowledge, corporate theories give birth to value-creating strategic actions. More-effective managers compose more-accurate and powerful theories—theories that open a vista of valuable experiments—a pathway toward value and a domain of value creating actions. The history of the Walt Disney Company provides an exceptional illustration of a brilliant corporate theory.

The Greatest Theory Ever Told

Walt and Roy Disney founded Walt Disney Productions in 1923. It quickly became the world’s premier animator, as the brothers, chiefly Walt, made a series of important advances in the art, technology, and practice of animation. But it was in the late 1940s and early 1950s that Walt came up with what was arguably his greatest creation—a corporate theory for the company—a clearly defined picture of how it would sustain value creation in the entertainment industry.

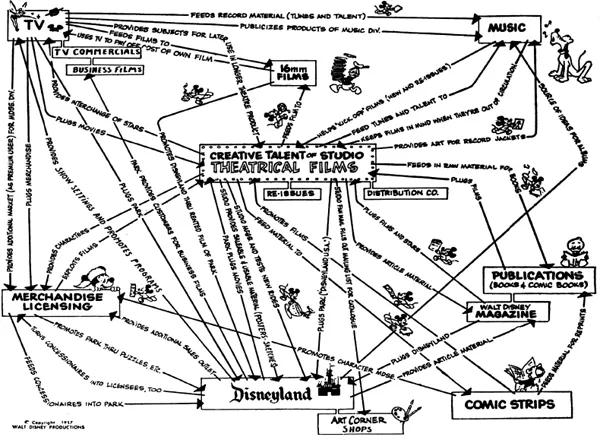

Walt Disney’s theory defined the firm’s composition, illuminated the relationships between the individual assets and resources that comprised it, and revealed paths for current and future investment. He captured this theory in the remarkable image shown in figure 1-1, which was retrieved from the Walt Disney Archives. It depicts a range of entertainment-related assets—book publishing, music, magazine publishing, comic books, theme parks, and consumer products—surrounding a core activity in film production, particularly animated film. The archives contain several versions of this theory, which evolved over time.

The drawing also describes a massive web of synergistic connections between these distinct businesses and assets, many linking directly to the central animated film asset. Comic strips “promote films,” and films “feed material to” comic strips. The theme park, Disneyland, “plug[s] movies,” and film “plug[s] [the] park.” TV “publicize[s] products of the music division,” and the film division “feeds tunes and talent to” the music division. This picture is more than just an asset description. It visualizes how these assets can be tightly linked to one another as complements, so that the value of one activity or asset is enhanced by the presence of another. As noted in the introduction, Walt Disney’s theory might be summed up as follows:

FIGURE 1-1

Walt Disney’s theory of value creation in entertainment

Source: The Walt Disney Company. © 1957 Disney

Disney believes that noble, engaging characters composed in visual fantasy worlds, largely through animation, will have vast and enduring appeal to children and adults alike, and Disney will sustain value-creating growth by developing an unrivaled capability in family-friendly animated and live-action films and then assembling other entertainment assets that both support and draw value from the characters and images developed within these films.

Walt Disney’s theory of value creation contained several key elements. It defined a valuable and unique asset; it identified patterns of complementarity among all assets; and it implicitly revealed an image of the future evolution of the industry. While this theory clearly evolved with time, the core elements never changed. This corporate theory did not merely define a position in the market; rather, it provided a road map for decades of future investments—a trajectory of growth for sustained value creation. The company continued to identify and assemble new products, services, and assets that fit the theory. Ultimately, the success of this theory played out in product market performance as its pursuit garnered either price or cost advantages in product markets. For instance, The Walt Disney Company enjoyed significant cost advantages in publishing, because it could cheaply export animated images and dialogue from its films; generating a best-selling children’s book for Disney cost a fraction of what its competitors would pay for the same type of product. Similarly, thanks in part to its investments in animated films, Disney could charge higher prices in theme parks and still draw tremendous traffic.

In many ways, the power of Walt Disney’s theory was most evident in the firm’s performance decline following his death. Leadership at The Walt Disney Company first transitioned to Card Walker and then to Ron Miller, Disney’s son-in-law and former Los Angeles Rams receiver, whom Walt had persuaded to leave football to join the organization. Surprisingly, within fifteen years of Walt Disney’s death, the company seemed to have lost complete sight of his theory, and by the early 1970s, its investments had even shifted away from animated films. In the process, the engine of value creation ground to a halt. Gate receipts at Disneyland flattened. Film revenues sagged. Character licensing fees from consumer products also dropped. The TV show The Wonderful World of Disney, for which American families gathered to watch every Sunday in what seemed like a nationwide group embrace, was dropped from network broadcast, then relaunched on Saturday evenings, only to be definitively dropped from the networks with the launch of the company’s cable channel. By the late 1970s, the Disney franchise many had grown to love as young children had seemingly disappeared.

So deep was the company’s strategic disarray that in 1984, corporate raiders attempted the unthinkable—a hostile acquisition. In the process, they threatened to essentially dismantle Disney. Saul Steinberg, the notorious corporate raider, took a 6 percent ownership position in Disney and quickly moved toward acquiring 25 percent of the company’s equity. To fund this takeover, Steinberg proposed to dismantle Disney and lined up outside investors eager to acquire key assets such as its film library and the prime real estate surrounding its theme parks. The capital markets clearly signaled that Steinberg’s proposed dismantling was more valuable than The Walt Disney Company on its current path. The board was faced with the choice of maintaining Ron Miller as CEO, selling the assets to Saul Steinberg, or finding new management.

It went for the third option, hiring Michael Eisner, who promptly rediscovered Walt Disney’s original theory of how to create value in entertainment. Guided by it, Eisner invested heavily in animated productions, with Jeffrey Katzenberg leading the effort. What followed was a string of hits beginning with Oliver & Company and followed by The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King. Box office share grew from 4 to 19 percent and its share of the video rental and video sales income jumped from 5.6 to 21 percent.

Eisner also pushed Disney’s character licensing aggressively, resulting in an eightfold growth in the operating income of this business between 1984 and 1994. Attendance and margins at the theme parks rose dramatically, requiring more investments in hotels to serve the sevenfold increase in Disney park attendees. Eisner also diversified into new assets and activities, including retail stores, cruise ships, Broadway shows, and live-action films.

Notably, these new investments followed logically from the Disney theory. Broadway shows drew characters and storylines from animated films. Cruise ships adopted characters and adapted entertainment from theme parks and Broadway shows. Retail stores promoted all of Disney’s assets, including theme parks, cruises, and extensive lines of character-related merchandise. By essentially dusting off Walt Disney’s theory and aggressively pursuing strategic actions consistent with it, Michael Eisner led The Walt Disney Company to phenomenal value creation. Under his leadership, Disney’s market capitalization shot up from $1.8 billion in 1984 to $28 billion by 1994.

It was a remarkable run, but it finally ran out of steam. Between 1994 and 2004, the company’s cumulative growth in value was a mere 22 percent. What went wrong? It’s possible that Disney had simply exhausted all valuable strategic experiments that the theory revealed, and what remained was the pursuit of opportunities and assets unlikely to yield value. Thus, while the move into Broadway shows was strongly complementary with animated films, character licensing, and theme parks, other strategic moves—such as the acquisition of a local Los Angeles TV station or the purchase of the California Angels baseball team—lacked the same synergies. If this were the case, the theory’s inability to reveal new sources of value was the direct cause of Disney’s stagnant share price and it was time to create a new theory.

The alternative explanation is simply that Disney had again lost its way and had failed to take actions or make investments consistent with its theory. Much like the period following Walt Disney’s death, the company’s core asset, animation, had atrophied substantially during the latter decade of Eisner’s leadership; many blamed his abrasive management style for the loss of key animation talent. Bottom line—the animation group had failed to keep up with technology trends and ownership of the best-in-the-world animation asset had consequently drifted from Disney to Pixar. Although Disney had access to this asset through a contract for five CGI animated films, its value-creation machine was powered by an engine that it did not own. Relations between Disney and Pixar grew increasingly contentious and finally broke down entirely just before Eisner stepped down. Disney’s new CEO, Robert Iger, clearly recognized the centrality of animation in the Disney theory and quickly moved to purchase Pixar, spending more than $7 billion dollars. In doing so, he restored Disney’s ownership of the unique asset most central to its theory of value creation (I take up discussion of this specific incident in chapter 4).

More interestingly, perhaps, is that Iger identified potentially new core assets that he believed would complement Disney’s constellation of capabilities and resources: the superhero franchise of Marvel Comics and the Lucasfilm/Star Wars franchise. Both feature characters very different from the princess-heavy character set that Disney had historically generated and sustained. It remains to be seen whether these assets represent an extension of Walt Disney’s original theory of how value creation worked and will broaden the terrain the organization’s value-creating machine can cover, or whether these actions will force Disney to modify its theory. But whatever the outcome of the Marvel and Lucas experiments, it is indisputable that Walt Disney’s theory of value creation for The Walt Disney Company provided a road map for value-creating growth that endured many decades past his death—a remarkable illustration of the power of theory to carry on the intentions and sustain the success laid down by one brilliant leader.

The Three “Sights” of Strategy

The Disney strategy has all the hallmarks of a powerful corporate theory. It has consistently given senior managers enhanced vision—a tool to repeatedly use in selecting, acquiring, and organizing complementary bundles of assets, activities, and resources. Importantly, Walt Disney’s graphic representation was not really a strategy per se, but rather a guide to the selection of strategies—a theory that would shape value-creating strategic actions, including acquisitions, investments, and organization design.

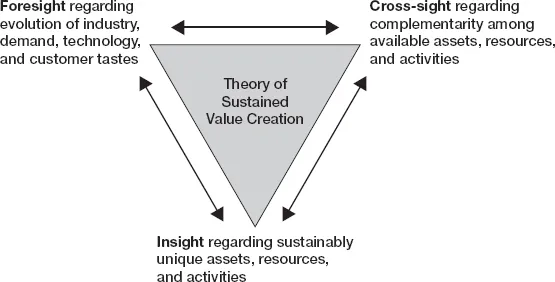

As briefly discussed in the introduction, corporate theories provide managers with enhanced vision, sight, or perspective in three key ways, as depicted in figure 1-2. First, they define foresight regarding an industry’s evolution in technology and customer demand and tastes. Second, they provide insight regarding sustainably unique assets, resources, and activities possessed by the firm. Third, they provide cross-sight—revealing patterns of complementarity between assets, activities, and resources both within and outside the firm. Let’s look at each of these components in turn.

FIGURE 1-2

Pillars of corporate theory

Foresight

An effective corporate theory...