- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

HBR Guide to Leading Teams (HBR Guide Series)

About this book

Great teams don't just happen.

How often have you sat in team meetings complaining to yourself, "Why does it take forever for this group to make a simple decision? What are we even trying to achieve?" As a team leader, you have the power to improve things. It's up to you to get people to work well together and produce results.

Written by team expert Mary Shapiro, the HBR Guide to Leading Teams will help you avoid the pitfalls you've experienced in the past by focusing on the often-neglected people side of teams. With practical exercises, guidelines for structured team conversations, and step-by-step advice, this guide will help you:

- Pick the right team members

- Set clear, smart goals

- Foster camaraderie and cooperation

- Hold people accountable

- Address and correct bad behavior

- Keep your team focused and motivated

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access HBR Guide to Leading Teams (HBR Guide Series) by Mary Shapiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

Build Your Team’s Infrastructure

Chapter 1

Pull Together a Winning Team

If you’ve ever led a team, you’ve dealt with maddening members: Those who dominate meetings. Slowpokes who analyze every problem from every angle when the schedule is tight. Those who harp on reasons not to support decisions the group made months ago. Quiet folks who say nothing in meetings, but then complain endlessly at the coffee station about decisions that were made in their presence. Those who compete for “resident expert” status without actually contributing much at all.

You may have wondered: Do they stay up all night thinking of ways to torment me? What’s wrong with them? Why can’t they be more like me?

That’s a common—though a bit melodramatic—response to the challenge of leading a team of diverse individuals. Socially we all gravitate toward people who are like us—those who understand our humor, enjoy doing the same things we do, and don’t get offended when we cancel at the last minute (after all, they do it, too). Sameness minimizes conflict and misunderstanding. Yet, to paraphrase U.S. gum maker William Wrigley Jr. when two people think alike on a team, one of them is redundant. Assemble a team of people who are just like you, and you’ll undoubtedly experience less frustration. The group will reach decisions more quickly, and members will approach the work in the same way.

But lack of diversity has a serious downside. If everyone on the team prefers big-picture thinking, who comes up with the practical steps necessary to realize the group’s vision? If everyone likes taking risks, who plans a soft landing before you leap? Who handles the tasks you don’t like to do or can’t do well?

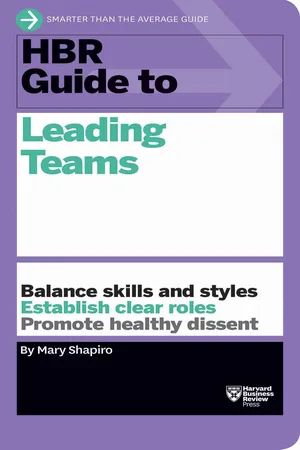

Research repeatedly shows that greater diversity on a team yields more innovation and higher-quality work. That’s why each individual on your team should bring some unique combination of expertise and skills that will help you produce great work (see figure 1-1).

To achieve the diversity “sweet spot” you’re aiming for, you must first envision the results you want, and then determine what strengths and capabilities you’ll need to achieve them. If you’re building a business case, for instance, you’ll need expertise in data mining and proposal writing. Tap your network for people who are good at those things or ask your colleagues whom they’d recommend. Once you’ve got someone on board who possesses a critical skill, don’t add another team member who excels at the same thing. Remember to address both task-related strengths and people skills when assembling your team.

FIGURE 1-1

Making the most of diversity

Use this list of task- and people-related strengths to determine what mix of knowledge and skills your team requires.

Consider this hypothetical example illustrating the value of diversity on a team.

Imagine that your company has experienced a dramatic increase in products returned from customers. If you pull together a team of six engineers to analyze the problem, chances are they’ll quickly come to one conclusion and make a recommendation consistent with their common backgrounds: It’s an engineering issue, and the solution is to rework the design.

I know this is a cliché, but it applies here: When everyone on your team is a “hammer,” then every problem will look like a nail, and every solution will be to pound it. Outcomes will be quick, consistent, and harmonious—but not innovative.

Now suppose you add people from customer service and marketing to your team. Team members will look at the problem from different viewpoints. Maybe it’s an engineering problem, maybe customers don’t understand how to use the product correctly, or maybe they’re buying the wrong model for their purposes.

That’s the good news—a variety of perspectives expands the number of possible solutions. But the team still must work together to come up with a single creative solution. The decision making takes much longer, and relationships may get strained as members hash out conflicting ideas.

So what’s the right amount of diversity? Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith define the optimal makeup of a team in their classic Harvard Business Review article “The Discipline of Teams” this way: “A small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.”

Building on this definition and drawing on my years of experience consulting with teams and leading my own, I’ve developed the following principles for assembling an effective team:

Make It Small

The larger the team, the more difficult it is to find meeting times, the longer it takes to make decisions, and the tougher it is to manage information and work flow. So bring together the smallest number of people necessary to provide the skills and perspectives you need. That’s usually somewhere between three and seven members. Other contributors who will be needed only occasionally—organizational allies, content experts, and advisers—should not be included as full-fledged members: That just wastes everyone’s time. Instead, consult them at specific points and assign one member to serve as a conduit of information back and forth. For example, a finance representative should weigh in as you put together a budget request for a project, but that person obviously shouldn’t participate in all the team building and ongoing work that doesn’t require financial expertise.

If you are assuming leadership of an existing team, you’ll need to start by deciding whom to keep and whom to cut loose. If the numbers feel bloated, consider defining a core team of a few essential people and moving others onto a “support” team that you enlist on an ad hoc basis. This strategy is particularly useful if you have inherited some noncontributors, complainers, or obstructionists. If you can’t eliminate them, you can at least marginalize their impact.

Incorporate Skills and Knowledge

List the skills and types of expertise you’ll need to tackle the team’s responsibilities—not just what’s needed to accomplish the work but also what will facilitate collaboration. (Again, use figure 1-1 to get started.) Then identify the fewest number of people who can cover most of those requirements.

You can also conduct this inventory to reevaluate your current team. If certain members aren’t contributing much, ideally you’ll remove them. But if you don’t have that authority, try giving them “support team” status as suggested above. Does your team lack key competencies? Add people to fill those gaps—or at least identify advisers you can call on periodically.

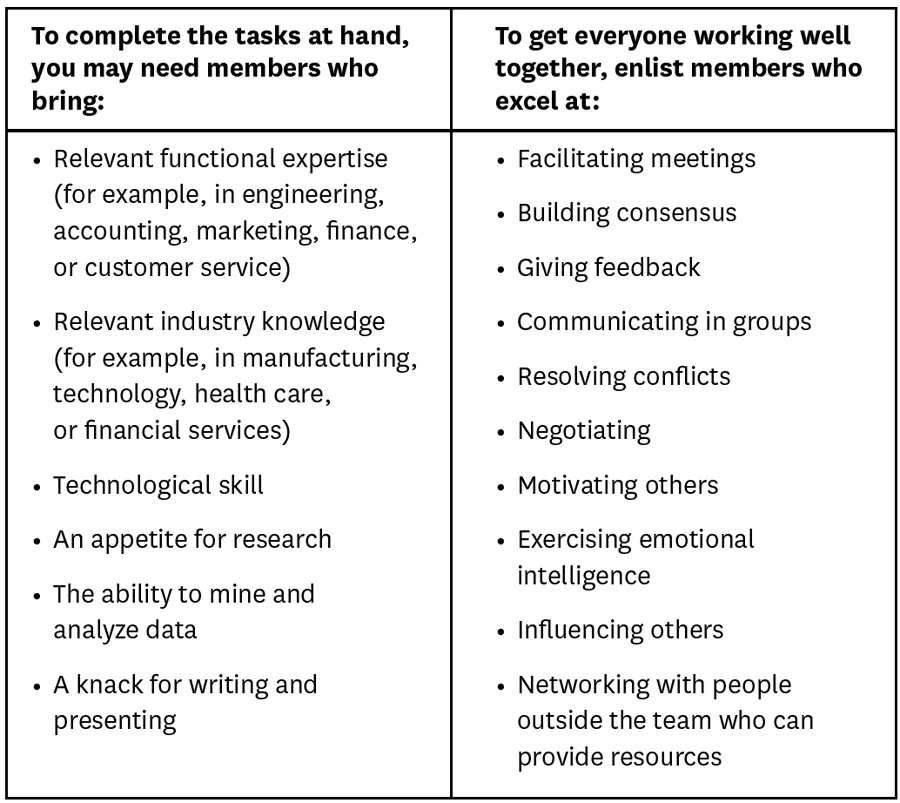

Include Diverse Approaches to Work

The best teams offer a mix of work styles: people who carefully address one task at a time and those who can multitask, folks who excel at contingency planning and those who nimbly adjust when problems strike, and so on. Here, we’re talking about people’s natural inclinations, not the skills they’ve acquired through training or experience. When assembling your team, consider how people differ in their outlooks, priorities, and attitudes about decision making, change, and risk.

Don’t drive yourself crazy trying to include every conceivable work style on your team. It’s just not possible. But identify people whose wiring differs from your own and who possess characteristics essential for your team’s success. If you’re leading a team that will drive deep change in the organization, you may want members on both sides of the “change” spectrum: early adopters to generate creative ideas and late adopters to anticipate sources of resistance (see figure 1-2).

FIGURE 1-2

How are they wired?

When you’re selecting team members, think about how they’re naturally inclined to act. On each dimension below, most people will gravitate toward one end of the continuum or the other when they’re on “autopilot,” though they can adjust their behaviors with effort—when under deadline pressure, for instance.

Though work quality will benefit from a mix of personalities and approaches, relationships may suffer. For example, the big-picture thinkers might regard the detail-oriented people as data geeks crippled by “analysis paralysis.” And the detail people may dismiss the big-picture folks as unrealistic or people who “shoot from the hip.”

Why would you want both types on your team? Imagine how much work would get done with only big-picture thinkers to execute ideas. Probably very little. They’d generate lots of excitement and creative thought, but the goals would keep changing and expanding, and no one would focus on how exactly to accomplish them. And you wouldn’t be any better off with an entire team of detail-oriented colleagues. They’d provide clarity, structure, and solid documentation of progress—but their outcomes would probably resemble what’s been done in the past. They wouldn’t break new ground.

So the differences are worth the potential headaches. We’ll talk more about how to handle the conflict—both destructive and beneficial—that is a natural by-product of diversity in chapter 11, “Resolve Conflicts Constructively.” But let’s now look at ways to minimize the headaches by anticipating some of the problems members will have.

Chapter 2

Get to Know One Another

Now that you’ve identified the skills and expertise your project needs and pulled together your team, it’s time for your launch meeting. You’ve made a PowerPoint deck outlining the project. You’ve provided coffee and donuts, and everyone’s sitting around the table expectantly. How do you begin? If you’re like most of us, you welcome everyone, introduce yourself, and then ask each person to share his or her name, title, and maybe “a little about yourself.”

But hang on. Don’t zip past those introductions. Before you dig into that deck and start explaining and organizing tasks, it’s essential to gather some personal data to help the group establish effective goals, roles, and rules of conduct. I’m not suggesting that your team members should share their favorite reality TV shows or “fun facts” about themselves. Rather, I’m encouraging you to connect with them in a meaningful way so that you—and the rest of the group—will know what each person needs to do his or her best work.

Begin by addressing the fundamental questions they’re privately contemplating while munching on their donuts:

- Why am I on this team, and what are your expectations of me?

- Why are others on this team?

- How do you see us working together?

If your team members understand why you chose them, they’ll have a clearer sense of how they can contribute. And just as important, they’ll learn what other team members bring to the table. You’re also helping people recognize from the outset the purpose for the team’s diversity, so they’ll be less likely later to snipe about how some members “leap before they look” and others can’t “analyze their way out of a paper bag.” By naming differences from the beginning, you’re acknowledging the need to work across them and highlighting the value each person brings.

Having everyone say “Hi, my name is Ellen, and I’m from St. Louis” doesn’t accomplish any of that.

As the team leader, you’ve intentionally chosen people with complementary skills and perspectives. Now you need to shed light, in a series of group conversations, on members’ personal strengths, work styles, and priorities.

Personal Strengths

Each member’s skills, knowledge, and work style will add to the pool of valuable team resources. A simple way of getting the group...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- HBR Press Quantity Sales Discounts

- Copyright

- What You’ll Learn

- Contents

- Introduction

- Section 1: Build Your Team’s Infrastructure

- Section 2: Manage Your Team

- Section 3: Close Out Your Team

- Appendix A: Rules Inventory

- Appendix B: Cultural Audit

- Appendix C: Team Contract

- Index

- About the Author