![]()

Section 1

Before You Get in the Room

The best negotiator is the most prepared one.

Preparation is the key to any successful negotiation, but few people spend enough time on it. I’ve had sales leaders tell me that they prepare in accordance with how long it takes to get to their customer’s office. That’s fine if your meeting is in Tokyo and you live in Manhattan. But it’s abysmal if you’re meeting the customer in Brooklyn.

Prepare as far in advance of the negotiation as possible. Take time to:

- Question your assumptions about the negotiation

- Think through what you want from the negotiation and why—and what the other party wants and why

- Get creative about your options

- Consider objective standards to apply to your options

- Assess your best alternative (and theirs)

- Plan how you’ll manage communication and your relationship with your counterpart

- Lay the groundwork for a successful negotiation by reaching out to the other party in advance

Doing all of this ahead of time gives you the advantage in the room. You’ll be able to better control the process and shape the outcome.

In the next chapter, I’ll discuss how to overcome some of the more common negative assumptions that you may hold as you go into conversations with your counterpart. Then, in the rest of this section, I’ll address how to prepare for both the substance and the logistics of your negotiation.

![]()

Chapter 2

Question Your Assumptions About the Negotiation

Develop new, more empowering expectations.

As you launch into the preparation process, you may already have a lot of assumptions about how your negotiation will go, many of them negative. You may suspect that there is only one option the other party will agree to (because your counterpart has never budged from his stated policy) or that the negotiation itself will be unpleasantly contentious (because that’s always been your experience).

But assumptions like this can be dangerous and limiting: They hinder your creativity. For example, if you think the other party is going to cling to a specific policy, you’ll be focused on combating it directly and unlikely to throw out more-inventive options that may actually get you and your counterpart something better. Or if you assume the other party is going to push hard, you might send signals that you’re going to do the same, without even realizing it.

Take, for example, a salesperson working with a procurement manager. The salesperson might think, “Well, the procurement manager has never gone for a risk-sharing deal in the past, so let’s not even bring that up this time.” This assumption will cause him to hold back what might be a viable solution for both sides, and if the purchaser learns he’s holding something back because he’s underestimated him, he risks damaging the relationship. Perhaps most dangerously, the salesperson could be leaving value on the table by not mentioning the option he’s hiding. A relatively simple shift in thinking—from “He’ll never go for that” to “If I never try, I’ll never know if he might go for some new, creative options”—can positively change the negotiation.

As you begin preparing, take a closer look at the assumptions you’ve already made and how they might be holding you back. Then challenge them, and see if you can shift them. Continue this process for the entire negotiation, checking to see what assumptions you’ve made and recasting them if necessary.

The salesperson in the example might, after all, offer risk sharing as an option: “I know you haven’t been interested in the past, but we’ve changed how we structure these deals to address the accounting issues you raised. It might solve the pricing issue, so I wanted to test this out again and see if we might be able to make it appealing for both of us.”

Even if the purchaser says no, the salesperson has demonstrated his understanding of his counterpart’s interests and his willingness to be collaborative and open to creative solutions.

Be Aware of the Assumptions You Often Make

In order to go into a negotiation with an open mind, you must first become cognizant that you hold particular assumptions that may be limiting your perspective. That’s not as easy as it sounds, because these notions are often deeply embedded; they often feel like objective truths rather than subjective beliefs.

Common negative assumptions fall into two categories: premature judgments about your counterpart, and those about the negotiation more generally:

About the other party

- As in the example with the salesperson, you may expect your counterpart to do certain things based on prior experience with her: “She’ll never go for an equal partnership” or “She always acts nice until the very end.”

- Even if you’ve never negotiated with the person, you guess how she’s going to behave based on where she’s from or her role: “People from the Northeast are aggressive; those from the West Coast are laid back” or “People in procurement care only about the bottom-line price; engineers care only about the quality of the product and are pushovers when it comes to actual cost.”

About how the negotiation will go

- You may assume that business negotiations are always formal, protracted, and overly focused on terms and conditions, or that certain kinds of personal negotiations are always contentious or zero sum, such as those about asking for a raise, purchasing a car, or buying a house.

As you’re preparing for your negotiation, think back to past negotiations, or other types of work situations, and list assumptions you made that turned out to be false. Try to spot patterns and identify the kinds of assumptions you typically make.

Then review the list and ask yourself which of these are pertinent to the current situation. As you do, add any other assumptions that come to mind about the negotiation at hand.

Shift Your Assumptions

Once you have a list of your assumptions, for each item, ask yourself whether it’s possible that the assumption is not true and then what it would take to disprove it. Depending on how you answer, there are a number of ways to change your thinking.

Shifting your assumptions about the other party

Hard data is one of the best ways to refute a myth. Find people who know the person or organization with whom you’re going to negotiate. Talk to others who have worked with him. You might even find people who have a similar job as your counterpart and can give you a sense of what the person might care about, what pressures he may be under, or what his interests might be. Gather as many facts as you can that might disprove, or at least challenge, what you’re given to believe.

If you don’t have access to those facts, invite some of your trusted colleagues to a meeting where you can explain what your assumptions are and ask that they systematically challenge them. Give them permission to poke holes in your theories, and they can help you see things from a different perspective.

Shifting your assumptions about how the negotiation will go

To address your negative ideas about how the negotiation will go, reframe them into “enabling” assumptions—ones that support a more positive outcome. (If you aren’t able to disprove myths about the other party, this approach can work for her as well.)

To do so, imagine how you would act if your belief weren’t true. This is what the salesperson did in the example earlier: Realizing his possibly faulty and debilitating assumption—that his counterpart was likely to be “yet another unimaginative procurement manager” who would never even consider discussing a risk-sharing deal, and therefore that it wasn’t worth even raising the idea—he jotted down a few ways in which risk sharing could work (both for him and his counterpart). Armed with this list, he is ready to share this information with the procurement manager in the negotiation itself in order to both test his openness to the idea and persuade him how it could benefit each of them.

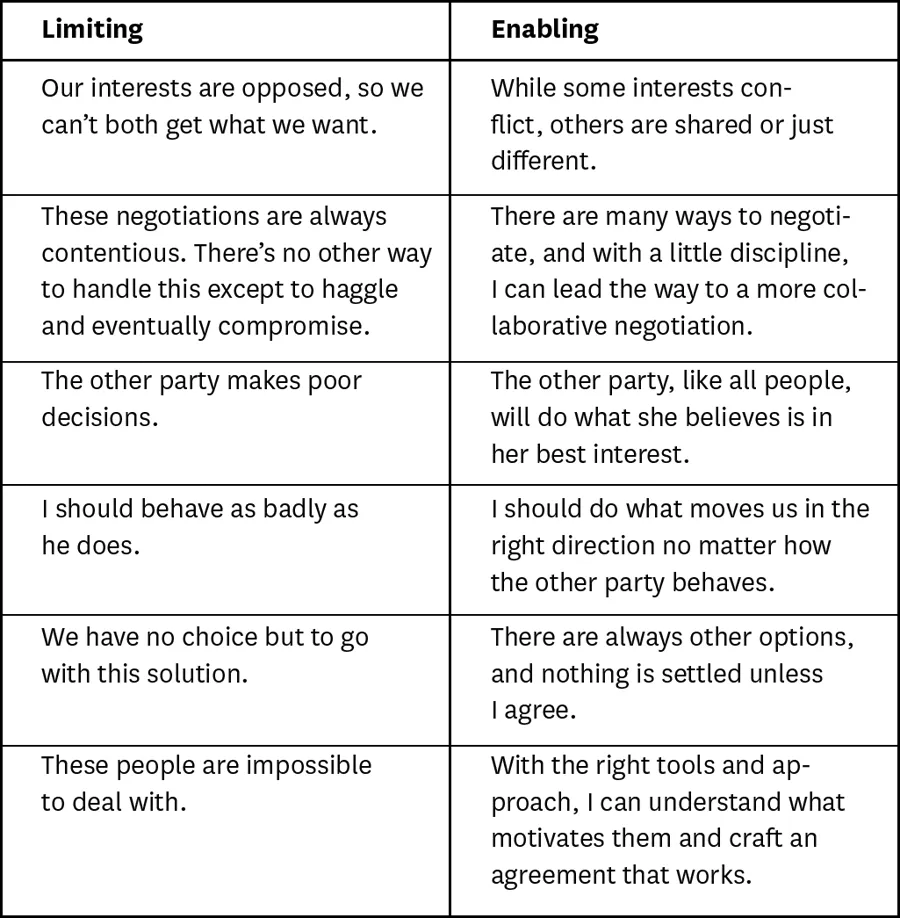

In table 2-1, I’ve listed some other limiting assumptions and their more enabling partners.

TABLE 2-1

Shifting your assumptions about the negotiation

Copyright © 2013 Vantage Partners, LLC. All rights reserved.

Look to Be Surprised

Throughout your interactions with your counterpart, continue to look for data that challenges your assumptions. Consider assigning someone on your team to be a watchdog; his job is to keep an eye out for any evidence that proves your expectations wrong. Maybe you presumed that the other party was going to be unbending, but you notice a willingness to involve new people in the discussion or to share information that you never thought she’d reveal: It looks like it’s time to revisit your beliefs about her.

Also question your assumptions anytime you get stuck in the negotiation. Go back to your list and see which of the thoughts you wrote down might be holding you back at this particular moment. If you could disprove or reframe any of them, would it help you move the process forward?

Finally, review your assumptions after the negotiation is over. Look over the list and determine what you’ve learned. Record the new lessons so that you don’t make the same mistakes next time. (I’ll go into more detail on learning from your negotiation in section 4.)

Keep in mind that many of your assumptions, even negative ones, will be proven correct once you’re in the room. After all, you made many of them based on past experience, and that can be a good guide. Perhaps the other party does make poor decisions or is particularly stubborn. But shifting to a more positive belief anyway will get you beyond those limitations. If you assume that you or the other party cannot get creative, change the course of the negotiation, fix the relationship, or trust each other, you never will.

![]()

Chapter 3

Prepare the Substance

Understand interests, brainstorm options, research standards, and consider alternatives.

To be agile and creative in a negotiation, you need to prepare for both the substance and the process—what you will say and do and also how you say and do it. You’ve been ...