![]()

PART I

Strategy, Organizations, and Control

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This book provides a new, comprehensive theory for controlling business strategy. Over the past two decades, management theorists and economists have devoted a great deal of energy to understanding strategy formation in competitive markets. They have developed techniques for analyzing the relative economic advantage of differentiated product and service offerings, but they have paid relatively little attention to understanding how to implement and control strategies. Yet the best-laid plans are worthless unless business managers understand the tools and techniques of strategy implementation.

Notwithstanding recent advances in theories of organization and strategy, the tenor of management control reaches back to the 1960s. A “command-and-control” rhetoric underlies phrases associated with traditional management control: top-down strategy setting, standardization and efficiency, results according to plan, no surprises, keeping things on track.

But command-and-control techniques no longer suffice in competitive environments where creativity and employee initiative are critical to business success. Increasing competition, rapidly changing products and markets, new organizational forms, and the importance of knowledge as a competitive asset have created a new emphasis that is reflected in such phrases as market-driven strategy, customization, continuous improvement, meeting customer needs, and empowerment.

The tension between the old and the new reflects a deeper tension between basic philosophies of control and management:

| Old | New |

| Top-down Strategy Standardization According to Plan Keeping Things on Track No Surprises | Customer/Market-Driven Strategy Customization Continuous Innovation Meeting Customer Needs Empowerment |

How can organizations that desire continuous innovation and market-driven strategies use management controls that are designed to ensure no surprises? How can empowerment and customization be reconciled with management controls that seek to standardize and ensure that outcomes are according to plan?

In searching for answers to these questions, we cannot dismiss too quickly traditional means of control. We can ask just as easily how empowered organizations guard against flawed decisions by subordinates who may not share the same goals or information as senior management, or how far-flung, complex businesses achieve constancy of purpose if continuous innovation results in needless experimentation and conflicting initiatives.

Understanding how to control empowered organizations in highly competitive markets is important for both theorists and practicing managers. My colleague Michael Jensen concluded his 1993 presidential address to the American Finance Association with this enjoinder, “Making the internal control systems of corporations work is the major challenge facing economists and management scholars in the 1990s” (Jensen 1993).

A new theory of control that recognizes the need to balance competing demands is required. Inherent tensions must be controlled, tensions between freedom and constraint, between empowerment and accountability, between top-down direction and bottom-up creativity, between experimentation and efficiency. These tensions are not managed by choosing, for example, empowerment over accountability—increasingly, managers must have both in their organizations.

This book presents a comprehensive theory illustrating how managers control strategy using four basic levers: beliefs systems, boundary systems, diagnostic control systems, and interactive control systems. The solution to balancing the above tensions lies not only in the technical design of these systems but, more important, in an understanding of how effective managers use these systems. The four control levers are nested—they work simultaneously but for different purposes. Their collective power lies in the tension generated by each lever.

Control and Control Systems in Organizations

Control in organizations is achieved in many ways, ranging from direct surveillance to feedback systems to social and cultural controls. Rathe noted some fifty-seven connotations of the term control (1960, 32). Clearly, terminology can cause confusion if not defined precisely.

This book focuses primarily on the informational aspects of management control systems—the levers managers use to transmit and process information within organizations. For the discussion to follow, I adopt the following definition of management control systems: management control systems are the formal, information-based routines and procedures managers use to maintain or alter patterns in organizational activities.

Several features of this definition are important. First, I am concerned primarily with formal routines and procedures—such as plans, budgets, and market share monitoring systems—although we will also examine how these stimulate informal processes that affect behavior. Second, management control systems are information-based systems. Senior managers use information for various purposes: to signal the domain in which subordinates should search for opportunities, to communicate plans and goals, to monitor the achievement of plans and goals, and to keep informed and inform others of emerging developments (Figure 1.1).

These information-based systems become control systems when they are used to maintain or alter patterns in organizational activities. Desirable patterns include not only goal-oriented activities—ensuring that new stores open on schedule—but also patterns of unanticipated innovation—discovering that branch employees’ experiments with the layout of a store have doubled expected sales figures. Employees can surprise, and management control systems must accommodate intended strategies as well as strategies that emerge from local experimentation and independent employee initiatives. Finally, I am concerned with the control systems used by managers, not the host of control systems used lower in the organization to coordinate and regulate operating activities (e.g., quality control procedures for repetitive operations).

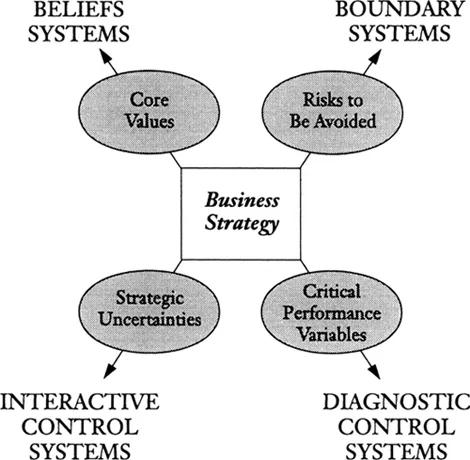

Figure 1.2 introduces the framework for the book. Business strategy—how a firm competes and positions itself vis-à-vis its competitors—is at the core of the analysis. The second level introduces four key constructs that must be analyzed and understood for the successful implementation of strategy: core values, risks to be avoided, critical performance variables, and strategic uncertainties. Each construct is controlled by a different system, or lever, the use of which has different implications. These levers are:

1.beliefs systems, used to inspire and direct the search for new opportunities;

2.boundary systems, used to set limits on opportunity-seeking behavior;

3.diagnostic control systems, used to motivate, monitor, and reward achievement of specified goals; and

4.interactive control systems, used to stimulate organizational learning and the emergence of new ideas and strategies.

These four levers create the opposing forces—the yin and yang—of effective strategy implementation. In Chinese philosophy, positive and negative forces are opposing principles into which creative energy divides and whose fusion creates the world as we know it. Two of these control levers—beliefs systems and interactive control systems—create positive and inspirational forces. These are the yang: forces representing sun, warmth, and light. The other two levers—boundary systems and diagnostic control systems—create constraints and ensure compliance with orders. These are the yin: forces representing darkness and cold. As I shall demonstrate, senior managers use these countervailing forces to achieve a dynamic tension that allows the effective control of strategy.

Selecting these levers—and using them properly—is a crucial decision for managers. Their choices reflect their personal values, reveal their opinions of subordinates, affect the probability of goal achievement, and influence the organization’s long-term ability to adapt and prosper.

Controlling Business Strategy

Before we develop principles for controlling strategy, we must have a clear understanding of what we mean by the term strategy. Like the concept of control, the definition of strategy seems straightforward until we attempt to describe it in practice; then we find ourselves unconsciously slipping into and out of several different meanings. Henry Mintzberg (1987a) identifies at least four distinct ways the term may be used—as a plan, as a pattern of actions, as a competitive position, and as an overall perspective. As we shall see, each of these is controlled by a different lever.

The most familiar usage recognizes strategy as a plan, or a consciously intended course of action. This view ties in most strongly with the military’s notion of strategy and tactics in which generals develop battle plans and issue instructions and field troops carry out orders. In this book, we examine the diagnostic control systems managers use to command and control through monitoring critical performance variables—the small number of variables essential to achieving intended business goals.

Strategy can be inferred from consistency in behavior, even if that consistency is not articulated in advance or even intended. Henry Ford offered his Model T only in black in the United States (and blue in Canada). Was this observable consistency a strategy? As Mintzberg states,

Every time a journalist imputes a strategy to a corporation or to a government, and every time a manager does the same thing to a competitor or even to the senior management of his own firm, they are implicitly defining strategy as pattern in action—that is, inferring consistency in behavior and labeling it strategy. They may, of course, go further and impute intention to that consistency—that is, assume there is a plan behind the pattern. But that is an assumption, which may prove false.

Thus, the definitions of strategy as plan and pattern can be quite independent of each other: plans may go unrealized, while patterns may appear without preconception. To paraphrase Hume, strategies may result from human actions but not human designs. (1987a, 13)

Managers control emerging patterns of action, often created by spontaneous employee initiatives, by using interactive control systems to focus attention on strategic uncertainties—uncertainties that could undermine the current basis of competitive advantage.

The view of strategy as position recognizes that firms choose different ways to compete in a product market. They may focus on differentiation of products, low cost, or specific customer groups (Porter 1980). Strategy as position focuses on the content, or economic substance, of the chosen strategy. Automobile manufacturers, for example, may choose to win market share by competing on either design features (BMW) or price (Hyundai). Managers attempt to control strategic position by using boundary systems to focus organizational attention on risks to be avoided—the identifiable, potentially severe risks that accompany choices about how to compete in chosen product markets.

Finally, many organizations such as Nike, Hewlett-Packard, and McDonald’s view the world in a way that is embedded in their history and culture. For these organizations, strategy can be analyzed as a unique perspective or way of doing things. Strategy in this respect is to the organization as personality is to the individual.

This [final] definition suggests above all that strategy is a concept. This has one important implication, namely, that all strategies are abstractions which exist only in the minds of interested parties. It is important to remember that no one has ever seen a strategy or touched one; every strategy is an invention, a figment of someone’s imagination, whether conceived of as intentions to regulate behavior before it takes place or inferred patterns to describe behavior that has already occurred.

What is of key importance about this [final] definition, however, is that the perspective is shared. As implied in the words Weltanschauung (German for “worldview”), culture, and ideology … strategy is a perspective shared by the members of an organization, through their intentions and/or by their actions. In effect, when we are talking of strategy in this context, we are entering the realm of the collective mind—individuals united by common thinking and/or behavior. A major issue of strategy formation becomes, therefore, how to read that collective mind—to understand how intentions diffuse through the system called organization to become shared and how actions come to be exercised on a collective yet consistent basis. (Mintzberg 1987a, 16–17)

To control this aspect of strategy, managers employ beliefs systems to communicate and control core values—the shared purpose of the business.

Implementing strategy effectively requires a balance among the four levers of control. This balance permits the simultaneous management of strategy as plan, pattern, position, and perspective. While management scholars have paid a great deal of attention to strategy formation, the control of strategy—that is, the control of the processes of strategy formation and implementation—has been relatively neglected. This book, then, presents an integrated theory for the control of strategy and illustrates the levers that turn theory to pr...