![]()

AN INTRODUCTION TO SUPERCONSUMERS

![]()

chapter 1

MAKING YOUR BEST CUSTOMERS BETTER

“Eddie, how do you think we should change the POG?” asked my client, Jeff Ackerberg, the vice president of sales and marketing of a major office-supply manufacturer. POG? I had no idea what he was talking about. The only thing that came to mind was passion-orange-guava juice from Hawaii, where I grew up. “We have a few different versions of the planogram for different retailers, but maybe you have a new idea?” Jeff continued.

The good news was that I figured out that POG was shorthand for planogram, but the bad news was that I still had no idea what a planogram was. Since I was a young consultant, just a few years out of college, I had never before helped a client with retail activation, so I wasn’t up to speed with the lingo. But after a long and uncomfortable pause, it hit me: a planogram probably referred to a diagram of a product display.

As my young career was flashing before my eyes, I fell back on the hundreds of hours I had spent listening to consumers of office supplies and the months I had spent analyzing data about what made these people tick. From my research, I knew that while the vast majority of office-supply consumers had zero emotional connection to paper clips, pens, and Post-It notes, one-third of these consumers were fanatics. I’m not kidding. There are people who love office supplies the same way some of us love bacon or our local sports teams.

A woman’s face popped into my head. Her name was Sally (not her real name), and she was one of the consumers whom my colleagues and I spoke with when we were researching the office-supply industry. A manager of a car rental agency, she rented hundreds of cars, vans, and trucks to long lines of customers each day. Often she felt set up to fail. She had to keep every promise made to a consumer with a reservation, but consumers could reserve and cancel without penalty or return their rental car earlier or later than their reservation mandated. Reconciling this uncertainty was difficult. And even when she was successful, she was left with a lot of paperwork to process, and the workload could get overwhelming.

Because of the frenetic nature of her job, Sally focused on things she could control. Specifically, she prided herself on her efficiency and organization. When she wasn’t dealing with a customer, she would make copies of the rental agreements, punch holes in the contracts, and organize them in a three-ring binder. She took this part of her job very seriously and appreciated any office supplies that were reliable and easy to use. Paperwork might seem like a chore to most people. But to Sally, a three-ring binder full of perfectly organized contracts was like a trophy for a job well done and her way of bringing order to chaos.

Through trial and error, she had settled on the best supplies for her job. The only exception was her hole puncher. Since it was a single-hole kind, she had to manually punch three holes in every page of over a hundred contracts per day. The repetitive task was a lot of work, and her hands would often cramp. But company bureaucracy made it a hassle to get a top-of-the-line three-hole puncher or an electric hole puncher.

Sally’s relationship with office supplies, however odd it seemed to me at first, was as rational as chefs’ love for their knives. When my colleagues and I gave her a heavy-duty, three-hole puncher as a thank you gift for speaking with us, she covered her mouth and was clearly touched. She told us afterward that this simple and inexpensive gift made her feel deeply understood and respected.

And Sally wasn’t alone. From our interviews and data crunching, we discovered that there were five million more consumers, just like Sally, who were passionate about office supplies. And this segment of consumers made up one-third of all consumers in the market in any given year. And better yet, they drove 70 percent of the profit.

Given those facts, we decided to pitch a novel idea: tailor the product display to Sally and her cohort of diehards. At the time, most office-supply stores placed cheaper, private-label products in their prime shelf space. Since stores didn’t think that consumers cared much about office supplies, they put the products with the lowest prices at eye level on the shelf. We went in the opposite direction. I suggested we move the heavy-duty and electric staplers and punchers from the bottom shelf to the eye-level one.

When we took our ideas to three major office-supply retailers, two retailers were impressed—they had never seen this depth of consumer insight in office supplies before and were willing to go along with the reset. In our planogram, we added signage that called out the high-performance staplers and punchers and praised the benefits of jam-free performance. We included electrical outlets so that customers could plug in the products to try them out.

We talked to other functional leaders about the two receptive retailers. We modeled the financial risk and upside with finance, discussed the inventory implications with the supply-chain people, and wrote retailer presentations for sales. Both retailers had doubts but conceded that even if we were partly right and sold even a few more higher-priced and higher-margin items, the return would more than offset any inventory and operational risk. We discussed with marketing if a big advertising campaign was necessary to push these high-end products. We decided against it, because we realized that Sally and those like her shopped or browsed these stores frequently—often, four times per month. Most other consumers shop these stores four times a year, if that. So there was no need for big marketing dollars to drive office-supply die-hards like Sally to the store, as they were already there. They needed to be romanced at retail. They needed to feel the heft of the heavy-duty stapler. They needed to hear the satisfying sound of the electric stapler. They needed to imagine a world without jammed staplers.

The retailers were pleased with the results. In nine months, heavy-duty and electric product sales doubled, and the total category went up 19 percent year after year. The third retailer, which had balked at our idea because we would be displacing its private-label products, saw its sales decline by 9 percent in the same period.

I often reflect back on that meeting with wonder and appreciation. I’m sure that the vice president of sales and marketing knew I was somewhat in over my head, but to his credit, he realized the same thing that I did—that consumers like Sally can be an extraordinarily powerful north star.

This is the essence of what I call a superconsumer strategy: find, listen to, and engage with your most passionate customers; understand their tastes, emotions, and behaviors; lean into the aspects that also resonate with a much larger group of potential superconsumers; and then tailor your decision making, coordinate and concentrate your cross-functional investments, and innovate—both your product and your business model—to give these consumers what they want and need. The strategy may seem obvious now, but in my experience of helping companies with their growth strategies, I’ve seen few managers take this approach to its fullest extent.

I’ve found that managers who fully embrace a superconsumer strategy, such as the office-supply manufacturer in the story above, learn more from their consumers through increased empathy. These managers are more persuasive at getting buy-in from the leaders in their organization, make better strategic decisions, and achieve more stable, more predictable, and longer-term growth.

MEET THE SUPERCONSUMERS

Any business can profitably grow. This may seem like a silly thing to believe when you look at the tombstones of businesses such as Circuit City and Motorola, the latter of which had the hottest mobile phone on the market just over a decade ago, but my faith comes from superconsumers like Sally.

Unlike heavy users (i.e., a product’s highest-volume buyers who are defined simply by the quantity of their purchases), superconsumers are characterized by their attitude as well: they are passionate about and highly engaged with—and maybe even a little obsessive about—a category (say, golf equipment, in the case of my dad). They are the sneaker-heads who own dozens of pairs of sneakers. They are the sports fans who own replica jerseys and hang signed memorabilia in their finished basements. They are bacon, chops, and carnitas-loving consumers who call themselves “pork dorks.”

Superconsumers aren’t random oddballs who buy in bulk. They’re emotional buyers who base their purchase decisions on their life aspirations. A superconsumer of Gatorade, for example, doesn’t just buy its products because he loves how they taste; he chooses the brand because it represents hard work, and Gatorade’s drinks, chews, and protein bars allow him to recover quicker during marathon training. He’s “hiring” Gatorade for a job, to help him improve his performance—an allegiance that also ties into a broader life quest, to train for a marathon. He’s deeply invested. He wants to “be like Mike.” The secret is realizing that for superconsumers, every category has “Gatorade-level” aspirations that can be tapped into.

The same goes for other superconsumers as well. A superconsumer of American Girl dolls sees the products as a way to connect with her grandchildren and spend more time with her family, and a private-label superconsumer sees value-priced groceries as a way to save money for a house while still feeding his family high-quality food.

Superconsumers can be an eclectic bunch who are hard to pin down. But thanks to our parent company, Nielsen, my colleagues and I at the Cambridge Group have access to an enormous amount of data about what people watch and buy. Specifically, we have mined Nielsen’s US Homescan database, which consists of approximately one hundred thousand US households that have agreed to have all of their purchases measured across all channels (down to the UPC level). With this information, we created a data set of over 125 consumer-goods categories that represented more than $400 billion in sales. We analyzed the purchase behavior of consumers across demographics and interviewed selected participants about the depth of their feelings about a particular category and why they valued it so much. Thanks to Jeff Eastman, the leader of the Homescan business at Nielsen, we have hundreds of statements from the households about the benefits sought, the emotions felt, and the aspirations held for all these categories.

Because of Nielsen’s data set (which is unique in its combination of emotion and economics), we’ve become superconsumer whisperers, in a sense. We know what makes these people tick and what makes them so beneficial to businesses of all kinds—not just office-supply manufacturers and consumer-goods companies.

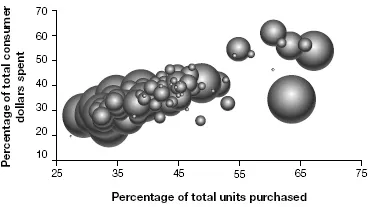

The biggest benefit of superconsumers comes down to simple math. Although superconsumers are few in number—usually about 10 percent of consumers for a particular product or category—they can drive between 30 percent and 70 percent of sales, an even greater share of category profit, and usually close to 100 percent of the insights (figure 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1

Superconsumers: the top 10 percent (across 124 consumer packaged goods categories with at least $400 billion in sales)

Source: Nielsen.

And they aren’t particularly price-sensitive. Since they have emotional and aspirational connections to the products they love, they’re willing to pay a premium for them as long as those products offer additional benefits that are appealing.

Common sense might suggest that there would be little return on investment (ROI) in trying to sell an office-supply superconsumer who owns eight staplers a ninth or a tenth one. But our analysis proves that selling those additional staplers to superconsumers is a smarter growth strategy than simply selling replacements for broken or lost staplers to normal consumers, because superconsumers buy more products at higher prices. But more important, these consumers are also gurus who can help you innovate and can act as pied pipers who spread the word to other...