![]()

PART

I long to accomplish a great and noble task, but it is my chief duty to accomplish humble tasks as though they were great and noble. The world is moved along, not only by the mighty shoves of its heroes, but also by the aggregate of the tiny pushes of each honest worker.

— Helen Keller

![]()

Who Tempered Radicals Are and What They Do

tempered \’tem-perd\ adj 1 a : having the elements mixed in satisfying proportions: TEMPERATE b : qualified, lessened, or diluted by the mixture or influence of an additional ingredient: MODERATED

radical \ra-di-kel\ adj 1 : of, relating to, or proceeding from a root . . . 2 : of or relating to the origin: FUNDAMENTAL 3 a : marked by a considerable departure from the usual or traditional: EXTREME 4 b : tending or disposed to make extreme changes in existing views, habits, conditions, or institutions1

MARTHA WILEY sits in her tenth-floor office in a prestigious highrise building in downtown Seattle. Decorated with earth-tone sofa and chair, overgrown ivies, and floor-to-ceiling ficus tree, her office looks as if she has inhabited it for years. Traditional management books line her bookshelves, interrupted only by a few recognizable volumes on women and management, a stone abstract carving of a woman and child, and a half-dozen silver-framed pictures of her two children and husband. Neatly stacked piles of paper cover her desk, suggesting that an orderly and busy executive sits behind it. Only running shoes and sweats in the corner disrupt the traditional mood of this office.

At 44, Martha has spent the past ten years working her way up to her current position as senior vice president and highest-ranking woman in the real estate division of Western Financial. She shows no sign of slowing down. From the time Martha walked into her office at 7:00 A.M. until this last meeting of the day at 5:30 P.M., she has sprinted from one meeting to the next, stopping only for a one-hour midday workout. This last meeting, before she rushes home to relieve her nanny, was requested by one of her most valued employees to talk about “the future.” Her employee nervously explains that since returning from maternity leave with her second child, she has found it increasingly difficult to be in the office five long days each week. She needs to find an alternative way to continue performing her job.

After thirty minutes, the two women agree to a plan: the employee will work two days from home and three days in the office, and every other week she will take one day off. Martha’s only request is that the employee remain flexible and be willing to come into the office when it is absolutely necessary for her work.

Martha is pleased that she can meet this employee’s needs. In fact, she has actively looked for opportunities to initiate changes that accommodate working parents and that make her department more hospitable to women and people of color. A full 30 percent of her staff now have some sort of flexible work arrangement, despite a lack of formal policy to guide these initiatives. Martha has little doubt that her experiments in work arrangements, even though she has kept them quiet, have been slowly paving the way for broader changes at Western. She had heard that word of her successes was spreading, and that it was only a matter of time before the institution caught up to her lead. (Eventually, the organization did initiate some policies that have given employees more flexibility in arranging their work schedules.)

This example is typical of Martha’s approach to change at Western. Though her agenda for change is bold—she wants nothing less than to make the workplace more just and humane—her method of change is modest and incremental. Martha constantly negotiates the path between her desire to succeed within the system and her commitment to challenge and change it; she navigates the tension between her desire to fit in and her commitment to act on personal values that often set her apart. As a result, she continues to find ways to rock the boat, but not so hard that she falls out of it.

All types of organizations—from global corporations to small neighborhood schools—have Marthas. They occupy all sorts of jobs and stand up for a variety of ideals. They engage in small local battles rather than wage dramatic wars, at times operating so quietly that they may not surface on the cultural radar as rebels or change agents. But these men and women of all colors and creeds are slowly and steadily pushing back on conventions, creating opportunities for learning, and inspiring change within their organizations.

Sometimes these individuals pave alternative roads just by quietly speaking up for their personal truths or by refusing to silence aspects of themselves that make them different from the majority. Other times they act more deliberately to change the way the organization does things. They are not heroic leaders of revolutionary change; rather, they are cautious and committed catalysts who keep going and who slowly make a difference. They are “tempered radicals.”2

Competing Pulls

Tempered radicals are people who operate on a fault line. They are organizational insiders who contribute and succeed in their jobs. At the same time, they are treated as outsiders because they represent ideals or agendas that are somehow at odds with the dominant culture.3

People operate as tempered radicals for all sorts of reasons. To varying extents, they feel misaligned with the dominant culture because their social identities—race, gender, sexual orientation, age, for example—or their values and beliefs mark them as different from the organizational majority. A tempered radical may, for example, be an African American woman trying to make her company more hospitable to others like herself. Or he may be a white man who holds beliefs about the importance of humane and family-friendly working conditions—or someone concerned for social justice, human creativity, environmental sustainability, or fair global trade practices that differ from the dominant culture’s values and interests.

In all cases they struggle between their desire to act on their “different” selves and the need to fit into the dominant culture. Tempered radicals at once uphold their aspiration to be accepted insiders and their commitment to change the very system that often casts them as outsiders. As Sharon Sutton, an African American architect, has explained, “We use our right hand to pry open the box so that more of us can get into it while using our left hand to be rid of the very box we are trying to get into.”4

Tempered radicals are therefore constantly pulled in opposing directions: toward conformity and toward rebellion. And this tension almost always makes them feel ambivalent toward their organizations. This ambivalence is not uncommon. Psychologists have found that people regularly feel ambivalent about their social relations, particularly toward institutions and people who constrain their freedom. Children, for example, regularly hold strong opposing feelings, such as love and hate, towards their parents.5 Sociologists have observed a comparable response in employees toward their organizations. They frequently counter organizational attempts to induce conformity and define their identities with efforts to express their individuality.6 People who differ from the majority are the most likely targets of organizational pressures toward conformity, and at the same time they have the greatest reason to resist them.

A Range of Responses

If ambivalence is the psychological reaction to being pulled in opposing directions, how does it lead people to behave? Some people make a clear choice, relieving their ambivalence by moving clearly in one direction or the other.7 Others become paralyzed and ultimately so frustrated that escaping the situation is their only relief. Some people flame out in anger. They grow to feel unjustly marginalized and focus on how to avenge perceived wrongs. They feel victimized by their situation and ultimately come to be at the mercy of their own rage. While the pain and anger are often justified, they can become debilitating.

Tempered radicals set themselves apart by successfully navigating a middle ground. They recognize modest and doable choices in between, such as choosing their battles, creating pockets of learning, and making way for small wins.

Tempered radicals also become angry, but they mitigate their anger and use it to fuel their actions. In the world of physics, when something is “tempered” it is toughened by alternately heating and cooling. Tempered steel, for example, becomes stronger and more useful through such a process. In a similar way, successfully navigating the seemingly incongruous extremes of challenging and upholding the status quo can help build the strength and organizational significance of tempered radicals.8

Note, though, that tempered radicals are not radicals. The distinction is important. The word radical has several meanings: “of, relating to, or proceeding from a root,” or fundamental, as well as “marked by a considerable departure from the usual or traditional,” or extreme.9 Tempered radicals may believe in questioning fundamental principles (e.g., how to allocate resources) or root assumptions, but they do not advocate extreme measures. They work within systems, not against them.

Martha, for example, could stridently protest her firm’s employment policies or could take a job within an activist organization and advocate for legalistic remedies to the inequities she perceives. But she has chosen the tempered path, in part because she believes that she can personally make more of a difference by working within the system. Her success has created a platform from which to make changes—often seemingly small and almost invisible—which over time have the potential to affect many people.

Martha also has chosen her course because she likes it. She is quick to admit that she loves her job, takes pride and pleasure in moving up the corporate ladder, and enjoys the status and spoils of her success. She likes living in a comfortable home and taking summer vacations in Europe. While Martha clearly enjoys the privileges that come with success, she believes that the criteria by which the system distributes these privileges need to be changed. Does this belief make her a hypocrite? Or does it simply speak to a duality she and other tempered radicals constantly straddle?

A Spectrum of Strategies

Martha makes choices every day, some conscious, some not, in order to strike a balance. She is committed to chipping away at her “radical” agenda, but not so boldly as to threaten her own legitimacy and organizational success. What is the right balance to strike? More generally, how do tempered radicals navigate the often murky organizational waters to pursue their ideals while fitting in enough to succeed? How do they successfully rock the organizational boat without falling out?

These questions drove my research and form the heart of this book. Not surprisingly, there is no single formula for finding a successful course. Rather, tempered radicals draw on a wide variety of strategies to put their ideals into practice, some more forceful and open, others subtler and less threatening. By choosing among these strategies, each tempered radical creates the balance that is appropriate for him or her in a given situation.

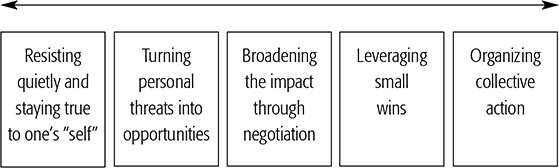

Figure 1-1 presents a spectrum of strategies. It is anchored on the left side by a collection of strategies I have labeled “resisting quietly and staying true to one’s ‘self,’” which includes acts that quietly express people’s “different” selves and acts that are so subtle that they are often not visible to those they would threaten. The other end of the spectrum, “organizing collective action,” reflects actions people take to get others involved in deliberate efforts to advance change. Martha’s initiatives around flexible work arrangements and similar strategies fall in the category of “leveraging small wins,” between the two endpoints.10

The spectrum varies along two primary dimensions. First, it speaks to the immediate scope of impact of a tempered radical’s actions. At the far left, only the individual actor and a few people in his or her immediate presence are likely to be directly affected by the action. At the opposite end of the spectrum, tempered radicals’ actions are meant to provoke broader learning and change. At the far left, the action is invisible or nearly so and therefore provokes little opposition; at the far right, the action is very public and is more likely to encounter resistance.

Figure 1-1: How Tempered Radicals Make a Difference

The second overlapping dimension is the intent underlying a person’s actions. At the left, people primarily strive to preserve their “different” selves. Many of these people who operate quietly are not trying to drive broad-based change; they simply want to be themselves and act on their values within an environment where that may feel difficult. Others who resist quietly do intend to provoke some change, but they do it from so far behind the scenes that the actions are not visible. At the right end of the spectrum, people are motivated by their desire to advance broader organizational learning and change. In reality, of course, no one person sits on a specific point on the spectrum, and the strategies themselves blur and overlap. I’ve distinguished them for the purpose of contrast, rather than to suggest that they reflect distinct responses. A few examples may help bring this spectrum to life.

Sheila Johnson is a black woman from a working-class family. She has worked her way up to senior vice president in the private equity division at Western Financial. Even though she is one of only a handful of black women in Western’s professional ranks, she thought that she would have a reasonable chance of succeeding here because of Western’s stated commitment to “diversity.” Sheila has tried over the years to keep a low profile, but when she has a chance to help other minorities, or when she feels she must speak up, she usually does so.

Sheila recalls a period when her division’s human resource manager complained about the inability to find and hire “qualified minorities” at every level. She knew that standard recruiting procedures at elite college and graduate schools did not constitute the kind of pipeline that would bring in enough diverse candidates to change the face of Western. So she took it upon herself to post descriptions of entry-level jobs throughout minority communities. She did not call attention to her intervention—she didn’t ask for permission or insist that the practice become recruiting policy. But through her quiet efforts, she helped create a more diverse pool of candidates, many of whom were hired into entry-level jobs.

Sheila could have broadened the impact of her actions by talking openly about them to enable others to recognize why their standard recruiting practices had failed to fill the bill. Had she made this link clear, she would have pushed others to learn from her ac...