The single most predictive element of the success of a gender initiative is leadership. In companies that successfully rebalance, the issue of gender balance is strongly and visibly led by the CEO. The CEO understands that the minds he needs to change are mostly among his existing (and usually male-dominated) management teams, and that those people will require strong convincing by someone who is perceived as credible.

FRONTLINE FEEDBACK: “Two years ago the CEO said [gender] was on his agenda, and that has created a real behavior change in the company.”

Yet most companies give the leadership roles for their gender initiatives either to their most senior woman (who often heads up HR), to their women’s network, or to the head of diversity. This approach simply serves to underline that it is a women’s issue or a diversity dimension rather than a business priority. (The exception is in companies where the head of diversity reports directly to the CEO and is effectively positioned as a strategic change agent.)

FRONTLINE FEEDBACK: “I think that leadership is the main stumbling block. It has to come from the top. The women’s network has delivered a whole bunch of recommendations, and they were all laughed off with somewhat snide remarks. Nothing is going to change until that group visibly changes its attitude.”

Start Smart

For companies that feel like they are behind on the diversity push and who don’t even have a head of diversity, congratulations. That offers an opportunity to avoid some of the mistakes from which we have learned. One of them is about how to lead the change.

Rather than setting up a separate diversity committee or women’s committee with dedicated resources, I recommend that companies instead assemble small, temporary, twenty-first-century leadership task forces. This is an efficient, flexible team with the knowledge and authority to make decisions and the seniority and business networks to influence key stakeholders. Such a team would emphasize the accountability of business leaders for making change happen.

FRONTLINE FEEDBACK: “Every Country Head should be leading on this topic, but I don’t know if they really are. We need alignment. Some are real believers, others are skeptics.”

Setting up diversity committees has deflected responsibility away from the people with the clout to implement change. Over the past decade, HR teams have been launching countless initiatives, doing a lot of research, setting up women’s networks, running women’s conferences, applying for awards, and establishing mentoring programs. Many are disillusioned—and tired. They feel like they understand the issues, that they’ve been struggling to get traction for years and are impatient with their bosses for the lack of gender balance evident at each new restructuring or round of promotions. They’ve been doing their job, so why don’t the executives walk their talk?

Because CEOs don’t buy it. Nor have most done enough to sell it. Here are three typical reactions, from three different companies, excerpted from the Qualitative and Quantitative QuickScan Audits we routinely do as a first step to analyzing where companies stand on gender issues:

- “Top leadership says it’s important, but they aren’t following up with the actions to support that strategic importance.”

- “We are doing this out of a sense of duty rather than any sense of conviction. So far it’s been a scorecard issue.”

- “This issue is not at all related to business. Is it an opportunity? No, that means we would discriminate the other way around. In politics, it’s OK to set quotas, we need rules because it’s a power issue; not in business, it’s a profit motive. So if gender were good for profits, companies would be better balanced already.”

In almost every session I run (in every company, in every country), the analysis of the top teams on the work that still needs to be done to promote gender balance is usually the same. The obstacles to achieving that balance typically cited by managers are a lack of skills in managing across genders and the mind-sets of the managers themselves. Managers either don’t understand or aren’t aware of the business case for more balance or don’t understand or aren’t aware of gender differences themselves.

So while many companies may be tired of hearing about a topic they feel they have been working on for decades, most firms have not even started the real work.

Sell the “Why” to the Senior Team

Why does your company want to achieve better gender balance? Your leaders need to make sense of this goal. Cisco CEO John Chambers sent a letter to his staff in 2013 announcing that “the result of creating a more equal environment will not just be better performance for our organizations, but quite likely greater happiness for all.”

Does his team buy this? Many progressive leaders don’t think they need to explain the “why” of gender balance. To them, it is a very obvious benefit to their businesses. But most managers don’t share this belief (if they did, more companies would be balanced already). And until they do—or your leaders have changed their minds—you can push all you like but are unlikely to improve your balance more in the next decade than you have in the past one.

Here is a series of reactions from a single leadership team on why gender balance is strategically smart for your business. You can see the range of opinions and general lack of alignment:

- I would rate gender balance as one of the top five factors for the company to succeed.

- Gender balance is very important in order for the company to grow.

- I believe the success of this organization will depend on greater gender balance.

- Yes, gender balance helps performance, but the benefit is not significant.

- Gender balance is a tactic that supports our strategy; it is not a strategy or an end in itself. We get no prizes for being gender balanced.

- Hmmmmmm, not sure.

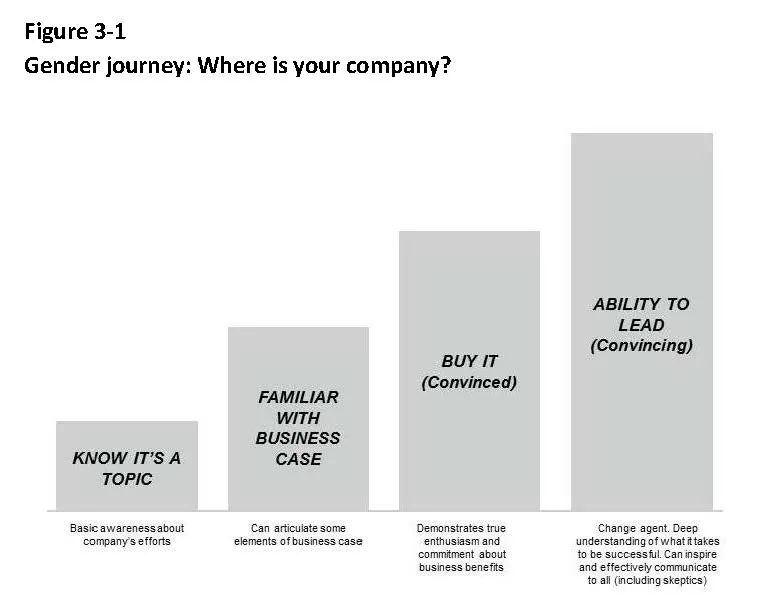

Companies that successfully gender balance do so because their leaders believe it will improve quality, culture, performance, and the bottom line—and they spend a lot of time and effort selling that belief to their colleagues. Do your managers get it? Do they buy it? Will they sell it to their colleagues? Take a look at figure 3-1, and see where your leaders stand.

Prepare the CEO

A rarely understood challenge is getting the CEO to play his (or, more rarely, her) part in the change. While strong CEO leadership is the number one criterion for successful gender balancing, not much has been written on the nature of leadership needed. Truly progressive men may not always be effective leaders on gender issues due to four blind spots that may influence their effectiveness. These blind spots can be addressed by building CEOs’ awareness of their attitude and its impact.

It’s a no-brainer.

Some intuitively progressive CEOs consider the case for gender balance so obvious that it doesn’t require elaboration or argument. These leaders don’t think they need to convince anyone of the benefits of balance. They don’t think anyone needs to hear any kind of business case anymore—that is yesterday’s battle. They assume their teams are all aligned behind them, and all they need to do is communicate a target. Such CEOs usually launch enthusiastically into the fray, over-communicating their goal and underestimating the incomprehension that usually meets their efforts. They end up frustrated a couple of years later at the lack of progress. These leaders often waste precious time and goodwill on ineffective approaches that respond to a partial understanding of the underlying issues and don’t take into account the potential reaction from their male majorities. Essentially, they charge out of the closet—and into a buzz of backlash.

As a result, these leaders often take overly aggressive approaches with unrealistic timelines. They either revisit the topic with more appropriate resourcing after a few years of unsatisfactory progress, or a successor quietly shelves their efforts.

It’s not worth fighting for (or being identified with).

Other CEOs are quiet supporters but don’t want to make it a big deal. It’s kind of like religion: something to be practiced quietly at home but not discussed in public.

This point of view is probably the one most commonly held by the progressive men I’ve met. Yet this majority status makes these men crucial to changing the cultures of the companies and countries where they work. Moreover, these individuals are currently developing, promoting, and financing tomorrow’s talent. This requires the skills and engagement to be proactively leading on gender issues. Yet in many of the sessions I run, it is the nay-sayers that are loud, assertive, and argumentative. The progressive men hold back, occasionally suggesting a caveat to a reactionary’s voluble bluster. It takes a lot of courage for men to stand up to other men on the topic of gender balancing.

Too many progressive men are taken aback by some of the heated reactions they encounter and often decide that gender is not enough of a priority to fight for. So they let louder voices dominate—and then drown—the debate.

It will happen naturally.

Some leaders argue that it is a simple case of meritocracy: recognizing and promoting the best people. They assume that, since the pipeline of colleges, graduate programs, and entry- to mid-level jobs are full of high-performing women, merit will win out and eventually women will start to make it in real numbers to the senior levels. Just as they have seen in their own teams. They think the issue is on its way to being solved naturally, without intervention.

In doing so, they underestimate their own skills and gender bilingualism. They don’t see that their own ability to recognize talent equally well among both men and women is an unusual skill that not all managers possess. They are usually reluctant to spend much time and effort equipping others with the skills and awareness that they themselves take for granted. This blind spot has much the same effect as the others: ineffective leadership on the issue.

I’m a champion, but not the right person to spearhead the effort.

Many progressive men still view any mention of the word “gender” as being about women, and they feel they should defer to female leadership on the topic. They ask their most senior women to take the visible leadership role, and they become “champions” or “sponsors” of the effort. They typically give the introductory remarks at their women’s networks’ events and meet with senior women to listen to their feedback, but they will rarely engage with their peers or other men on the topic at all. This reinforces the perspective that gender balance is an issue that is entirely in the hands of women, and that leaders have no accountability or responsibility on the topic, aside from encouraging the gal...