![]()

CHRONICLE TWO

THE EVIDENCE MAN

A conspiracy is everything that ordinary life is not. It’s the inside game, cold, sure, undistracted, forever closed off to us. We are the flawed ones, the innocents, trying to make some rough sense of the daily jostle. Conspirators have a logic and a daring beyond our reach. All conspiracies are the same taut story of men who find coherence in some criminal act.

—Don DeLillo, Libra

![]()

8

DEPARTMENT OF EASY VIRTUE

One day in the summer of 1925, Tom White, the special agent in charge of the Bureau of Investigation’s field office in Houston, received an urgent order from headquarters in Washington, D.C. The new boss man, J. Edgar Hoover, asked to speak to him right away—in person. White quickly packed. Hoover demanded that his staff wear dark suits and sober neckties and black shoes polished to a gloss. He wanted his agents to be a specific American type: Caucasian, lawyerly, professional. Every day, he seemed to issue a new directive—a new Thou Shall Not—and White put on his big cowboy hat with an air of defiance.

He bade his wife and two young boys good-bye and boarded a train the way he had years earlier when he served as a railroad detective, riding from station to station in pursuit of criminals. Now he wasn’t chasing anything but his own fate. When he arrived in the nation’s capital, he made his way through the noise and lights to headquarters. He’d been told that Hoover had an “important message” for him, but he had no idea what it was.

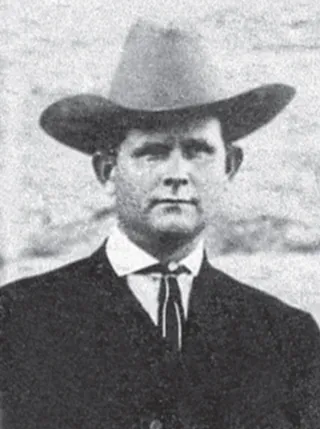

White was an old-style lawman. He had served in the Texas Rangers near the turn of the century, and he had spent much of his life roaming on horseback across the southwestern frontier, a Winchester rifle or a pearl-handled six-shooter in hand, tracking fugitives and murderers and stickup men. He was six feet four and had the sinewy limbs and the eerie composure of a gunslinger. Even when dressed in a stiff suit, like a door-to-door salesman, he seemed to have sprung from a mythic age. Years later, a bureau agent who had worked for White wrote that he was “as God-fearing as the mighty defenders of the Alamo,” adding, “He was an impressive sight in his large, suede Stetson, and a plumb-line running from head to heel would touch every part of the rear of his body. He had a majestic tread, as soft and silent as a cat. He talked like he looked and shot—right on target. He commanded the utmost in respect and scared the daylights out of young Easterners like me who looked upon him with a mixed feeling of reverence and fear, albeit if one looked intently enough into his steel-gray eyes he could see a kindly and understanding gleam.”

White had joined the Bureau of Investigation in 1917. He had wanted to enlist in the army, to fight in World War I, but he had been barred because of a recent surgery. Becoming a special agent was his way of serving his country, he said. But that was only part of it. Truth was, he knew that the tribe of old frontier lawmen to which he belonged was vanishing. Though he wasn’t yet forty, he was in danger of becoming a relic in a Wild West traveling show, living but dead.

President Theodore Roosevelt had created the bureau in 1908, hoping to fill the void in federal law enforcement. (Because of lingering opposition to a national police force, Roosevelt’s attorney general had acted without legislative approval, leading one congressman to label the new organization a “bureaucratic bastard.”) When White entered the bureau, it still had only a few hundred agents and only a smattering of field offices. Its jurisdiction over crimes was limited, and agents handled a hodgepodge of cases: they investigated antitrust and banking violations; the interstate shipment of stolen cars, contraceptives, prizefighting films, and smutty books; escapes by federal prisoners; and crimes committed on Indian reservations.

Like other agents, White was supposed to be strictly a fact-gatherer. “In those days we had no power of arrest,” White later recalled. Agents were also not authorized to carry guns. White had seen plenty of lawmen killed on the frontier, and though he didn’t talk much about these deaths, they had nearly caused him to abandon his calling. He didn’t want to leave this world for some posthumous glory. Dead was dead. And so when he was on a dangerous bureau assignment, he sometimes tucked a six-shooter in his belt. To heck with the Thou Shall Nots.

His younger brother J. C. “Doc” White was also a former Texas Ranger who had joined the bureau. A gruff, hard-drinking man who often carried a bone-handled six-shooter and, for good measure, a knife slipped into his leather boot, he was brasher than Tom—“rough and ready,” as a relative described him. The White brothers were part of a small contingent of frontier lawmen who were known inside the bureau as the Cowboys.

Tom White had no formal training as a law-enforcement officer, and he struggled to master new scientific methods, such as decoding the mystifying whorls and loops of fingerprints. Yet he had been upholding the law since he was a young man, and he had honed his skills as an investigator—the ability to discern underlying patterns and turn a scattering of facts into a taut narrative. Despite his sensitivity to danger, he had experienced wild gunfights, but unlike his brother Doc—who, as one agent said, had a “bullet-spattered career”—Tom had an almost perverse habit of not wanting to shoot, and he was proud of the fact that he’d never put anyone into the ground. It was as if he were afraid of his own dark instincts. There was a thin line, he felt, between a good man and a bad one.

Tom White had witnessed many of his colleagues at the bureau cross that line. During the Harding administration, in the early 1920s, the Justice Department had been packed with political cronies and unscrupulous officials, among them the head of the bureau: William Burns, the infamous private eye. After being appointed director, in 1921, Burns had bent laws and hired crooked agents, including a confidence man who peddled protection and pardons to members of the underworld. The Department of Justice had become known as the Department of Easy Virtue.

In 1924, after a congressional committee revealed that the oil baron Harry Sinclair had bribed the secretary of the interior Albert Fall to drill in the Teapot Dome federal petroleum reserve—the name that would forever be associated with the scandal—the ensuing investigation lay bare just how rotten the system of justice was in the United States. When Congress began looking into the Justice Department, Burns and the attorney general used all their power, all the tools of law enforcement, to thwart the inquiry and obstruct justice. Members of Congress were shadowed. Their offices were broken in to and their phones tapped. One senator denounced the various “illegal plots, counterplots, espionage, decoys, dictographs” that were being used not to “detect and prosecute crime but . . . to shield profiteers, bribe takers and favorites.”

By the summer of 1924, Harding’s successor, Calvin Coolidge, had gotten rid of Burns and appointed a new attorney general, Harlan Fiske Stone. Given the growth of the country and the profusion of federal laws, Stone concluded that a national police force was indispensable, but in order to serve this need, the bureau had to be transformed from top to bottom.

To the surprise of many of the department’s critics, Stone selected J. Edgar Hoover, the twenty-nine-year-old deputy director of the bureau, to serve as acting director while he searched for a permanent replacement. Though Hoover had avoided the stain of Teapot Dome, he had overseen the bureau’s rogue intelligence division, which had spied on individuals merely because of their political beliefs. Hoover had also never been a detective. Never been in a shoot-out or made an arrest. His grandfather and his father, who were deceased, had worked for the federal government, and Hoover, who still lived with his mother, was a creature of the bureaucracy—its gossip, its lingo, its unspoken deals, its bloodless but vicious territorial wars.

Coveting the directorship as a way to build his own bureaucratic empire, Hoover concealed from Stone the extent of his role in domestic surveillance operations and promised to disband the intelligence division. He zealously implemented the reforms requested by Stone that furthered his own desire to remake the bureau into a modern force. In a memo, Hoover informed Stone that he had begun combing through personnel files and identifying incompetent or crooked agents who should be fired. Hoover also told Stone that per his wishes he had raised the employment qualifications for new agents, requiring them to have some legal training or knowledge of accounting. “Every effort will be made by employees of the Bureau to strengthen the morale,” Hoover wrote, “and to carry out to the letter your policies.”

In December 1924, Stone gave Hoover the job he longed for. Hoover would rapidly reshape the bureau into a monolithic force—one that, during his nearly five-decade reign as director, he would deploy not only to combat crime but also to commit egregious abuses of power.

Hoover had already assigned White to investigate one of the first law-enforcement corruption cases to be pursued in the wake of Teapot Dome. White took over as the warden of the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, where he led an undercover operation to catch officials who, in exchange for bribes, were granting prisoners nicer living conditions and early releases. One day during the investigation, White came across guards pummeling a pair of prisoners. White threatened to fire the guards if they ever abused an inmate again. Afterward, one of the prisoners asked to see White privately. As if to express his gratitude, the prisoner showed White a Bible, then began to lightly rub a mixture of iodine and water over its blank fly page. Words magically began to appear. Written in invisible ink, they revealed the address where a bank robber—who had escaped before White became warden—was hiding out. The secret message helped lead to the bank robber’s capture. Other prisoners, meanwhile, began to share information, allowing White to uncover what was described as a system of “gilded favoritism and millionaire immunity.” White gathered enough evidence to convict the former warden, who became prisoner No. 24207 in the same penitentiary. A bureau official who visited the prison wrote in a report, “I was very much struck with the feeling among the inmates relative to the action and conduct of Tom White. There seems to be a general feeling of satisfaction and confidence, a feeling that they are now going to get a square deal.” After the investigation, Hoover sent a letter of commendation to White that said, “You brought credit and distinction not only to yourself but to the service we all have at heart.”

White now arrived at headquarters, which was then situated on two leased floors in a building on the corner of K Street and Vermont Avenue. Hoover had been purging many of the frontier lawmen from the bureau, and as White headed to Hoover’s office, he could see the new breed of agents—the college boys who typed faster than they shot. Old-timers mocked them as “Boy Scouts” who had “college-trained flat feet,” and this was not untrue; as one agent later admitted, “We were a bunch of greenhorns who had no idea what we were doing.”

White was led into Hoover’s immaculate office, where there was an imposing wooden desk and a map on the wall showing the locations of the bureau’s field offices. And there, before White, w...