![]()

The Irish in Gallipoli

Francis Ledwidge, 1917

Where Aegean cliffs with bristling menace front

The Threatening splendor of that isley sea

Lighted by Troy’s last shadow, where the first

Hero kept watch and the last Mystery

Shook with dark thunder, hark the battle brunt!

A nation speaks, old Silences are burst.

Neither for lust of glory nor new throne

This thunder and this lightning of our wrath

Waken these frantic echoes, not for these

Our cross with England’s mingle, to be blown

On Mammon’s threshold; we but war when war

Serves Liberty and Justice, Love and Peace.

Who said that such an emprise could be vain?

Were they not one with Christ Who strove and died?

Let Ireland weep but not for sorrow. Weep

That by her sons a land is sanctified

For Christ Arisen, and angels once again

Come back like exile birds to guard their sleep.

I

Things Fall Apart: Art Emerges from Conflict

1919. In Dublin, the artist Harry Clarke is struggling with a commission to illustrate an anthology of poetry edited by Lettice d’Oyly Walters, titled The Year’s at the Spring. Harrap’s in London has just published Clarke’s macabre illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. William Butler Yeats writes ‘The Second Coming’, reflections on the aftermath of the First World War. Dáil Éireann assembles in January, but by September is ruled illegal. Two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary are killed in Tipperary. The aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown cross the Atlantic in their First World War era Vickers Vimy bomber, landing in Clifden, Connemara. The complete poems of Francis Ledwidge, who was killed in the Battle of Passchendaele, are published posthumously.

The Treaty of Versailles is signed on 28 June 1919, marking five years to the day after the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Anarchy and revolution spread throughout Germany. In Berlin, Max Beckmann completes his painting, Die Nacht. On Bastille Day in Paris, a two-hour victory parade marches under the Arc de Triomphe, passing a towering pyramid of cannons along the Champs Élysées. In London, Edwin Lutyens designs a cenotaph to the dead and wounded that will be the centerpiece of Allied Peace Day celebrations. In Dublin, the Viceroy, Sir John French, decides that in Ireland, too, there will be a parade and a permanent memorial to the missing and wounded. Harry Clarke receives the commission to illustrate the eight volumes of Ireland’s Memorial Records.

Ireland’s Memorial Records are Commissioned

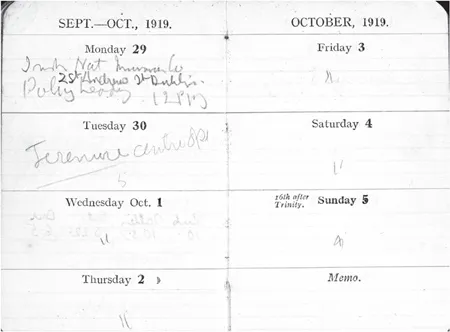

Ireland’s Memorial Records were commissioned in 1919 and published in 1923 by the Dublin firm Maunsel and Roberts.1 These volumes contain the names of 49,435 individuals of Irish birth, ancestry, or regimental association who were killed in action or died of wounds in the First World War. There are eight volumes and 100 sets of Ireland’s Memorial Records. They are distinctive as honour rolls because of the richly illustrated borders by Harry Clarke, who is recognized in Ireland as one of the foremost artists of the early twentieth century. Clarke contributed an evocative Celtic-themed title page and eight illustrated borders. When Harry Clarke was awarded the commission to create decorative margins for Ireland’s Memorial Records, the only trace he left of any conversations was a line in his pocket diary for 29 September 1919, which reads simply, ‘Irish Nat Memorials’.2

FIGURE 1.1

Harry Clarke Diary 1919. Image Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland, MS 39, 202 (B)(2).

One hundred years later, computer programs and web-based interfaces allow Ireland’s Memorial Records to be searched online for names, regiments, and dates of death. The ease of international access to the data has meant that the artistic achievement of Ireland’s Memorial Records has been lost. The artwork has been removed from the online search capability; the illustrations are considered secondary to the text, mere decoration. What if we were to set aside the text for a time and consider only the borders? What if Ireland’s Memorial Records were considered not a flawed collection of names, but a superior realization of memorial art?

Maunsel and Roberts were known for printing nationalist literature including J. M. Synge’s The Well of the Saints (1907) and the Collected Works of Padraic [Padraig] H. Pearse (1917). Thus, they were a suitable publisher for printing the roll of the Irish dead. Given the choice of publisher and artist it appears as though Clarke’s illustrations and George Roberts’s visual design were symbolic acts of repatriation of the Irish soldiers, removing them from Britain’s army into a realm of purely Irish aesthetics. Each volume of Ireland’s Memorial Records measures twelve inches by ten inches. Following the decorative title page, eight images are repeated throughout the volumes, in recto and verso (reversed) – including soldiers in silhouette, ruined houses, graves, trenches, the Gallipoli Peninsula, cavalry, airplanes, tanks, bursting shells and searchlights. Sets were delivered to libraries and cathedrals in Ireland, England, Canada, Australia, and the United States. A very fine set was presented to King George V on 23 July 1924 and, also at that time, a set was conveyed to the Vatican.3

Who was Harry Clarke? He is known as a talented and visionary stained-glass artist. He was born in Dublin, educated at Belvedere College, and left school at age 14 to enter into a series of apprenticeships. While he began to refine and perfect his stained-glass technique through plating and aciding the glass, he also was working on pen and ink illustration. In 1913, Clarke received the commission to illustrate the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen for George Harrap & Co., London and he was occupied with his illustrations and travels on the continent throughout 1914. When England declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Clarke did not enlist. From 1914 onward, he was dedicated to a commission to complete eleven stained-glass windows at the Honan Chapel in Cork, which are now considered among his masterpieces.4

The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Sir John French, instigated the idea for a national war memorial on 17 July 1919, the day prior to the Peace Day celebrations.5 The year marks the beginning of a great age of war memorials in Britain and the Commonwealth, with public and private monuments raised to commemorate over one million British troops dead or missing in the war. The pressing desire for post-war remembrance fostered two exhibitions held in London in 1919 by the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Academy War Memorials Committee. Clarke’s domestic stained-glass panel ‘Gideon’ was among the new works exhibited at the V&A exhibit that opened in July 1919.6 In Ireland, a core group that would become the sustaining subcommittee for Irish memorials came together at the 1919 meeting, including in particular, Andrew Jameson (director of the whiskey distillery) and Clarke’s patron, the former MP Laurence Waldron.7

This meeting in July 1919 resulted in two resolutions that were ‘unanimously passed’: first, ‘to erect in Dublin a permanent Memorial to the Irish Officers and men of His Majesty’s Forces who fell in the Great War’; and to prepare ‘parchment rolls’ upon which ‘should be recorded the names of Irish Officers and men of all services who had fallen in the war’.8 At this point in 1919, from the first meeting of a group of interested and, it appears, mostly loyalist parties, Ireland’s Memorial Records were joined with a permanent memorial structure to house them, which we know today as the Irish National War Memorial Gardens. Although Ireland’s Memorial Records were completed in 1923, the memorial would not be complete until 1938, the eve of Britain’s entry into the Second World War. Consequently, the memorial was not officially opened until 1988.9

Given an absence of historical records, it is difficult to answer with any certainty why Harry Clarke was chosen as the illustrator or Maunsel as the publisher. Extant historical documents are silent on the official decisions and parlour conversations that might shed light on the making of the books....