- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Greek Music in America

About this book

Winner of the 2019 Vasiliki Karagiannaki Prize for the Best Edited Volume in Modern Greek Studies

Contributions by Tina Bucuvalas, Anna Caraveli, Aydin Chaloupka, Sotirios (Sam) Chianis, Frank Desby, Stavros K. Frangos, Stathis Gauntlett, Joseph G. Graziosi, Gail Holst-Warhaft, Michael G. Kaloyanides, Panayotis League, Roderick Conway Morris, National Endowment for the Arts/National Heritage Fellows, Nick Pappas, Meletios Pouliopoulos, Anthony Shay, David Soffa, Dick Spottswood, Jim Stoynoff, and Anna Lomax Wood

Despite a substantial artistic legacy, there has never been a book devoted to Greek music in America until now. Those seeking to learn about this vibrant and exciting music were forced to seek out individual essays, often published in obscure or ephemeral sources. This volume provides a singular platform for understanding the scope, practice, and development of Greek music in America through essays and profiles written by principal scholars in the field.

Greece developed a rich variety of traditional, popular, and art music that diasporic Greeks brought with them to America. In Greek American communities, music was and continues to be an essential component of most social activities. Music links the past to the present, the distant to the near, and bonds the community with an embrace of memories and narrative. From 1896 to 1942, more than a thousand Greek recordings in many genres were made in the United States, and thousands more have appeared since then. These encompass not only Greek traditional music from all regions, but also emerging urban genres, stylistic changes, and new songs of social commentary. Greek Music in America includes essays on all of these topics as well as history and genre, places and venues, the recording business, and profiles of individual musicians. This book is required reading for anyone who cares about Greek music in America, whether scholar, fan, or performer.

Contributions by Tina Bucuvalas, Anna Caraveli, Aydin Chaloupka, Sotirios (Sam) Chianis, Frank Desby, Stavros K. Frangos, Stathis Gauntlett, Joseph G. Graziosi, Gail Holst-Warhaft, Michael G. Kaloyanides, Panayotis League, Roderick Conway Morris, National Endowment for the Arts/National Heritage Fellows, Nick Pappas, Meletios Pouliopoulos, Anthony Shay, David Soffa, Dick Spottswood, Jim Stoynoff, and Anna Lomax Wood

Despite a substantial artistic legacy, there has never been a book devoted to Greek music in America until now. Those seeking to learn about this vibrant and exciting music were forced to seek out individual essays, often published in obscure or ephemeral sources. This volume provides a singular platform for understanding the scope, practice, and development of Greek music in America through essays and profiles written by principal scholars in the field.

Greece developed a rich variety of traditional, popular, and art music that diasporic Greeks brought with them to America. In Greek American communities, music was and continues to be an essential component of most social activities. Music links the past to the present, the distant to the near, and bonds the community with an embrace of memories and narrative. From 1896 to 1942, more than a thousand Greek recordings in many genres were made in the United States, and thousands more have appeared since then. These encompass not only Greek traditional music from all regions, but also emerging urban genres, stylistic changes, and new songs of social commentary. Greek Music in America includes essays on all of these topics as well as history and genre, places and venues, the recording business, and profiles of individual musicians. This book is required reading for anyone who cares about Greek music in America, whether scholar, fan, or performer.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Greek Music in America by Tina Bucuvalas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Musical Genre, Style, and Content

Growth of Liturgical Music in the Iakovian Era1

—Frank Desby

Seldom has an art form been subjected to as strong a changing influence as the music of the Orthodox Church when it was brought to America. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, our music has been seriously impacted by the art and ethos of the New World. True, there was great influence of the Moslem world on our music after the late fourteenth century. This influence introduced some alterations in the scales upon which the melodies were constructed and rhythmic elements as well. Yet the basic concept of a single melodic line, without a background harmony, prevailed until the twentieth century. The Slavonic Church, on the other hand, developed a harmonic-contrapuntal choral idiom in the seventeenth century, while the Greek and Antiochian Orthodox retained the single melodic chant line, save for the held tone of the isokratai.

Harmonized choral music for the church did not originate in America. Greeks living in France and Germany experimented with harmonizations. Eventually, at the turn of the century, attempts at harmonized Byzantine chant were introduced by John Sakellarides.

Outside of Greece, one would expect to find choral music without much opposition, so it is no surprise that on Easter Sunday in 1844 in the Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity in Vienna, John Haviaras led a choir of twenty-four male singers in a four-part setting of the liturgical music. At the end of the nineteenth century, Spyro Spathis settled in Paris. He offered the Greek community harmonized settings for mixed chorus. Criticism of this early pioneer’s work lies in the fact that the subtleties of Byzantine scales are theoretically not adaptable to Western major-minor tonality. It is not our purpose here to discuss the possibilities of adapting one type of musical thought (Byzantine) to another (European) except to state that compromises, once believed unworkable, are possible.

In Athens, the influence of John Sakellarides on the musical habits or customs of the Greeks was minimal; it was in America that his influence became enormous. As an opera coach and music teacher at a number of schools, and also trained thoroughly as a psaltis (a precentor, or chanter), Sakellarides came into contact with a large number of musicians of varying backgrounds. In the 1920s he met Henry J. Tillyard, of England, who was with the British School at Athens. Tillyard became quite interested in Byzantine music and secured Sakellarides as his teacher. Together they explored some of the earlier layers of melodic tradition, noting that the melodic style and, indeed, the tonality had been subjected to several transformations. Music before the Turkish conquest (1453) was different, and every 150 years or so thereafter the melodies were subjected to “interpretations,” which the Byzantine composers called “exegesis.” The last transformation occurred during the last half of the eighteenth century, culminating in 1814 with a revision of teaching methods. Also, for the first time, in 1820, it became possible to engrave and print Byzantine music.

With this vehicle of mass reproduction, it was unfortunately only the latest style that became universally established. Little of the music of the older melourgoi survives today except in manuscripts. Furthermore, what melodies had survived had become decorated to the point of corruption. Sakellarides studied the early examples, combed out many ornaments, and produced a kind of classical reform. This purging upset his contemporaries. However, many of his simplified versions became standard, but not his harmonic versions.

With the migration of Greeks to the United States, beginning at the turn of the twentieth century, came some of Sakellarides’s students. They offered their services as psaltes and even as instrumentalists for community entertainment. The creation of language schools for the first generation of Greek American children created new demands from the church. In many instances, the local precentor was also the local Greek schoolteacher.

The influence of public school choral music, and its existence in local non-Greek churches, was strong enough to introduce in our churches some experimentation with choral music and a participating group—the choir. Separated from the Mother Church, the Greek church in the United States was not under the watchful eye of anyone objecting to innovations. So, in the first quarter of the twentieth century, the Greek church of the New World introduced choral music on a permanent basis.

Early Contributors

No one knows for sure where and when the first choir was formed in America’s Greek churches, or when organ accompaniment was introduced, but many have laid claim to being the originators. Among the early choir directors are the Sakellarides group, especially those who had their training under the Athenian master. These include Christos Vrionides and Angelos Desfis. Others who had come under Sakellarides’s influence were Nicholas Roubanis, George Anastassiou, and Athan Theodores. These few were singled out because they contributed published material to our churches.

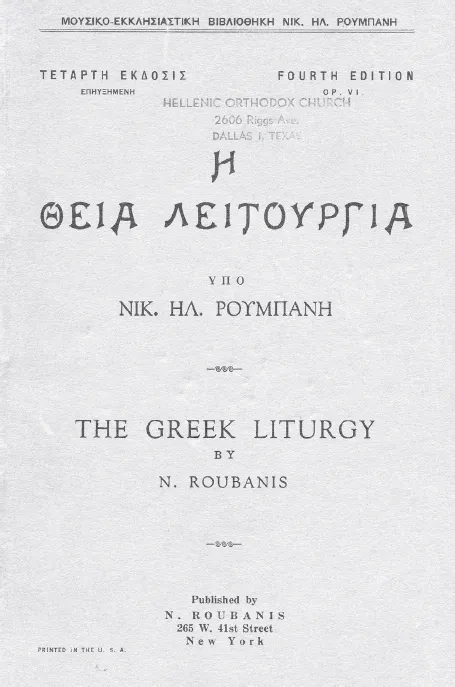

Figure 33. Nicholas Roubanis, I Theia Leitourgia: The Greek Liturgy. Photo by Tina Bucuvalas.

In each of the large cities, the precentors organized choral groups to take part in the liturgy and occasionally other akolouthiae for Holy Week and major feast days. The inclusion of young girls and women seemed to raise no objection by either the faithful or the clergy. Indeed, this seemed to be another vehicle for preserving the heritage, while in Greece the inclusion of women in church services is still not acceptable. The music brought to this country had been written for four-part male ensemble. It was soon discovered that with women now part of the choir, such writing was unsuitable. Rewriting was inevitable, as was the influence from non-Hellenic sources. Some of the new directors had received full formal training in Western music in addition to their Byzantine training. Here are brief profiles of these leading choir directors:

Figure 34. The Damaskenos Byzantine choir, directed by Father George Anastassiou, Tarpon Springs, Florida, 1934. Courtesy of Esther Raptis.

Christos Vrionides had received diplomas in the United States as well as Greece, was thoroughly trained on several instruments, and served as conductor of a number of symphony orchestras. By appointment of the federal government, he founded and conducted the Long Island Symphony in Babylon, New York. Vrionides was recognized in the 1951 Who’s Who of Music. Later, he became the music instructor at Holy Cross Seminary, teaching both Byzantine music and the formal music of the West. He wrote the first US-published treatise on Byzantine chant.

Nicholas Roubanis came to the United States in the twenties from Alexandria, Egypt, as a French horn player. He was active in Chicago for a number of years before moving to the East Coast, becoming involved with the musical growth of several communities. His “Divine Liturgy for Mixed Voices” was to become immensely popular due to its simplicity and effective part writing. His song “Misirlou” became an international hit in the popular music field. He was active in the church all his life; his final position was as a choir director in New Jersey.

George Anastassiou was a student in Cyprus of the famous Stylianos Chourmouzios but studied the choral settings of Sakellarides with great diligence when he immigrated to the United States and formed a choir in Tarpon Springs, Florida. Eventually he moved to Philadelphia, where he was the protopsaltis, directed the choir, and became a greatly respected music teacher. Anastassiou, like others about him, realized that the four-part male choir setting of Sakellarides could not be used with mixed voices. Therefore, he composed his own music for the Divine Liturgy. While the work of Anastassiou was similar to the liturgies of Vrionides and Roubanis, it introduced some additional material, contained both a major and minor version of the liturgy, and included information for use of the organ. Most valuable was an appendix of the special hymns needed throughout the ecclesiastical year. This material, appearing in Western staff notation, makes this volume indispensable. Probably no choir director even today is without one.

Athan Theodores’s and Angelos Desfis’s contributions consisted mostly of separate hymns of the liturgy, such as the Cherubic and Communion hymns. Privately published, their circulation was not extensive. In 1947, Desfis on a visit to Greece secured the publishing rights to Sakellarides’s Western notation liturgical book, Hymns and Odes, which explains how so important a transition work came to be printed in America.

Father Demetrios Lolakis studied at the Conservatory of Athens, becoming proficient in the piano and violin, which he played all his life. He came to the United States about 1927 and was active mostly in the Midwest. He transcribed an enormous amount of Byzantine music into staff notation and recorded much of this on tape. This contribution has proven to be quite valuable to priests and psaltes alike. After his ordination in 1922, his musical activities grew rather than becoming subordinate to parish duties; yet, as a parish priest, he was always highly esteemed. After his retirement, he continued his musical activities with undiminished interest and vigor.

The Postwar Period

At the outbreak of World War II, most churches had a choir of mixed voices, ages ranging from fifteen to twenty-five. They also had an organ of some kind, either a harmonium with pedals to pump the bellows or a simple electric instrument, and a choir director who might also be church secretary, psaltis, language teacher, or all three.

When the service members returned home, they displayed a new spirituality and renewed interest in their ethnic roots. This resulted in a welcome renaissance for the church. The returning military entered colleges and joined musical organizations there. As they participated in their local choir, they required the church to offer more challenging musical fare. In many cases, the liturgical repertoire remained identical to the prewar music, but standard choral music was added so that church-sponsored programs offered the community a broader selection. Many second-generation Greeks also majored or minored in music; therefore, as the original directors retired, the positions were filled by well-trained newcomers. As a result, more challenging types of music became manifest.

It should be mentioned that all of the archbishops of these periods, despite their traditional upbringing, encouraged the adaptation of choral music and inclusion of an accompanying instrument. A little-known but interesting piece of information concerns the introduction of a pipe organ to the church on the island of Kerkyra (Corfu) by then Metropolitan Athenagoras (later, archbishop of North and South America and, in 1949, ecumenical patriarch). Whenever a new prelate takes over, there is naturally some anxiety on the part of the clergy and laity as to whether progress will be maintained. It was therefore exceptionally fortunate for the Orthodox Church in America to have Archbishop Iakovos elevated to this post in 1959. Our new archbishop, extensively educated and cultured, was well aware of the worldwide religious situation. He was up to date on all facets of community life, education, spirituality, music, art, and architecture. Having traveled widely, he was not given to snap decisions nor did he impede progress in any field. With his encouragement and participation, the musical life of the communities flourished for many years. It was our good fortune to have a prelate who possessed experience and wisdom combined with good judgment.

Musical Styles

Some discussion of prewar and postwar (World War II) musical style is necessary to clarify the position of both the musical contributors and the hierarchy. The single-line melody of Byzantine chant (monophony) of the Church of Greece was rendered by two groups of precentors, explicitly guided by the rubrics or red-printed directions in the service books and the Typicon. Services in the early American churches (Annunciation, Chicago, 1893; Holy Trinity, New York, 1902; Holy Trinity, Boston, 1903) were followed by others, reaching fifty-two by 1962. The service music was certainly supplied by a right and left psaltis plus volunteers when available, carrying on the tradition of the Mother Church. Yet, here too, a kind of melting pot was created. Because not all psaltes came from Athens or the Peloponnese but from all over Greece and Asia Minor, a mixture of various styles was absorbed at large in the New World.

In 1902, the first edition of Sakellarides’s Sacred Hymnody was published in Byzantine notation in Athens. This was of little use to the American-based church except that the author had managed to write, for the first time, two-and three-part harmonizations in this notation, thereby giving Athenian congregations a taste of harmony. In 1930, he published this music in European staff notation. It was this music that was used by our earliest choirs. One can imagine that in America the Sunday School children were taught the melodies at first and introduced to harmonized versions soon after. Sakellarides’s music was reprinted in bootleg editions in those early days by Greek American newspaper publishers.

What was this music like? It consisted of the melody in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Overview of Greek Music in America

- Part One: Musical Genre, Style, and Content

- Part Two: Places

- Part Three: Delivering the Music: Recording Companies and Performance Venues

- Part Four: Profiles

- Appendix: Greek Music Collections in the United States

- Contributors

- Index