![]()

CHAPTER 1

Maryland on Trial

The Old Line State in the Civil War and the Trial of the Lincoln Conspirators, 1861–1865

Baltimorean Virginia Craig’s words to her husband U.S. Army captain Seldon Frank Craig just a few days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln targeted her native state. She met her husband while he was stationed in Baltimore, and they married in April 1864. In her April 19, 1865, letter, she remarked that even in Baltimore a “shadow of grief appeared to hover about the countenances of all of our loyal citizens, and indeed over many who have always been considered the enemies of Mr. Lincoln.” This expression of grief, however, was not enough for her to take pride in her home state.

Craig lamented her own connection to Maryland: “The South! How I detest the name, and everything with the horrid doctrine of Secession! How I wish that I had been born a ‘Yankee’ (though I once disliked them) or anything but a Marylander, for our state has produced some of the worst characters which this rebellion has brought to light.” She insisted that from “the 19th of April ’61 until the present time, the meanest most cruel and wicked acts of this accursed war (I blush to say it) have been done by Maryland villains.” In her mind, Craig did not believe anything “could have exceeded in wickedness and blood-thirstiness, the acts of the lawless mob on the 19th of April 1861,” with the exception of the “last desperate act of Maryland ‘rebels,’ the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.” Craig claimed that even among those responsible for the horrid conditions of Confederate prisons, “none were so harsh or so cruel as those who claimed Maryland as their native state.” She took comfort in the fact that Lincoln’s remains would not travel through Baltimore because “there would be too many who would look at them with joy in their hearts.” Craig’s disdain for the citizens of her own state underscored the divisiveness of Civil War Maryland.1

The American Civil War fractured and disrupted Maryland society deeply. The divides that developed over the issue of secession continued to grow throughout the course of the war and, unlike the fighting that ceased in 1865, remained long after its conclusion. Maryland’s schism over Union and Confederate identities and sympathies between 1861 and 1865 set the stage for debates and conflicts over postwar memory that persisted well into the twentieth century. Maryland during the Civil War era represented points of fracture for many of the states’ citizens as well as those outside the state. From the Baltimore Riot of 1861 to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Maryland was a focal point of the Civil War, and its centrality contributed to its conflicted legacy. Many in the state resisted the changes the war wrought and longed for a sense of equality that they felt the war unfairly hijacked. The trials Maryland faced in the mid-nineteenth century were only the beginning but nevertheless created a foundation for divided Civil War memories.

Maryland on the Eve of the Civil War

Maryland was divided years before the outbreak of the Civil War. The eastern and southern regions of the state were vastly different from the northern and western counties. The varied nature of the economies throughout Maryland played a central role in their dichotomous relationship. The Eastern Shore developed its own unique culture apart from the mainland portion of Maryland. With the growing inability to produce tobacco on the Eastern Shore, the region witnessed a dramatic decrease in the number of slaves and a tremendous rise in the number of free blacks in the decades prior to 1860. The white population grew wary of the growing free black population and struggled to sustain its farms financially in a region of the state that lacked significant land transportation.2

The issue of transportation marked the most important difference between the two regions. Western Maryland’s industries and economy experienced unprecedented growth in the first half of the nineteenth century with the construction of canals, railroads, and roads. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and the National Road played vital roles in expanding the reach of western Maryland and providing opportunities for export. By 1850, western Maryland was home to nearly “70 percent of the state’s total white population, nearly half of its free blacks, and less than 20 percent of its slaves.”3

What set southern Maryland apart from other portions of the state was the persistence of the institution of slavery and the region’s reliance on farming for the subsistence of its economy. Improved farming techniques and diversifying crop output aided the survival of white famers in southern Maryland. The white planter class in southern Maryland also enjoyed the benefits of new farming techniques and provided a steady demand for slave labor. The expansion of slavery into the southwest during the first half of the nineteenth century added value to slave labor and encouraged southern Maryland slave owners’ participation in domestic slave trading.4

Northern and southern Maryland was also divided on the eve of the Civil War. Historian Charles W. Mitchell notes, “Maryland’s economy in 1860 was a blend of Northern mercantilism and Southern agrarianism” and Baltimore “reflected this dichotomy.” The commercial development occurring in the city certainly resembled the growth of industry in the North, but the population of Baltimore emanated a more traditionally southern culture.5 Baltimore also possessed a complex black population in 1860. The free black population in the city numbered approximately 25,000 compared to 2,218 slaves. Competition for jobs with native and immigrant whites ultimately forced many free blacks in Baltimore to look elsewhere for work. Added to this complex racial society was the rise of the Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s. Founded and focused on nativist principles, the Know-Nothings thrived in Baltimore by preying on the fear of an ever-growing immigrant population.6

The growing sectionalism occurring throughout the United States in the years immediately preceding the outbreak of hostilities only furthered the divides in Maryland. Although the Know-Nothing Party emerged prominently in Baltimore during the 1850s, the issue of slavery subsumed it and other social concerns as the United States and Maryland grappled with heightened sectionalism. Historian Kevin Conley Ruffner notes that throughout the secession crisis “Marylanders could not decide whether they were northern or southern.”7 The presidential election of 1860 underscored the state’s conflicted position amid the growing sectional crisis. Although the nationwide election was a four-candidate race, there were only two candidates who garnered significant votes in Maryland: John C. Breckinridge, the southern Democrat from Kentucky, and Tennessean John Bell, representing the Constitutional Union Party. Breckinridge appealed to voters who were invested in the institution of slavery and favored the expansion of slavery into new territories in the United States. Bell advocated on behalf of compromise and devotion to the Union. Although Bell garnered votes across the state, he failed to win Baltimore. Breckinridge’s success in Baltimore, along with his popularity in southern and Eastern Shore counties, allowed him to claim the state’s electoral votes. Maryland was the northernmost state to give electoral votes to the southern Democratic candidate. The much-maligned “Black Republican” candidate, Abraham Lincoln, received less than 3 percent of the vote in Maryland.8

The election of Abraham Lincoln sent ripples of discontent across the state. Constitutional Union supporters were disappointed with Bell’s loss and fearful of the consequences of Lincoln’s election. Southern Democrats expressed their support for the first states to secede and pledged to contribute volunteers to their cause. White Marylanders feared that the racial foundation of their state was shifting beneath their feet. Lucinda Rebecca Beall of Frederick County, Maryland, wrote to her brother James Francis Beall, a teacher and farmer from Frederick, in the winter of 1860 in this growing climate of paranoia. “There has been a great talk about a company of abolishionist being in the mountain,” she warned. She confessed, “Some of the folks was afraid to sleep at night.”9

Not all Marylanders were disappointed with the results of the 1860 election. An African American man sat down among white passengers on a train in Baltimore and when he was confronted he responded “that Lincoln was elected, and he would ride like ‘any other man.’” The conductor removed the man from the train. The passenger believed that Lincoln’s election meant his equality was finally realized. He would inevitably be disappointed by the persistent racial inequality that would characterize Maryland for the rest of the nineteenth century and beyond.10

As other states seceded from the Union following Lincoln’s election, Maryland leaders wrestled with what course of action to take. Governor Thomas H. Hicks refused requests for a special session of the General Assembly, as it was an off-year for the legislative body, and in the first few months of 1861 individuals in counties across the state organized committees to discuss, debate, and promote actions on behalf of Maryland. In February 1861, James Beall received a letter from his uncle that expressed his fear that “Governor Hicks and Mister Davis will sell if not already don it Maryland to Black republicans.” The tensions between opposing sides in Maryland and the growing resentment of the president-elect prompted Abraham Lincoln to sneak through Baltimore in the middle of the night on February 22, 1861, en route to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration. Internal divisions were present in Maryland well before the country fully fractured in two, and the political developments of early 1861 highlighted the points of separation. The debates over Maryland’s position escalated into more visceral and physical expressions of conflict as the secession winter melted away and the reality of war became clear.11

The Baltimore Riot

One week after the first shots fired at Fort Sumter, the start of war for Marylanders and the rest of the United States echoed in the streets of Baltimore on April 19, 1861. Responding to Lincoln’s call for troops on April 15, federal troops scattered about the country made their way to Washington, D.C., to prepare for war and receive their orders. News of U.S. troops’ planned marching path through Baltimore reached the city’s citizens, and many southern sympathizers expressed their resistance to this action. Lincoln was aware of rumblings of discontent and potential unrest prior to the troops’ arrival in Baltimore. Secretary of War Simon Cameron wrote Governor Hicks on April 18 to implore him and the city of Baltimore to prepare for their arrival. He noted that Lincoln “thinks it his duty to make it known to you so that all loyal and patriotic citizens of your State may be warned in time and that you may be prepared to take immediate and effective measures against it.” In the eyes of Cameron and Lincoln, the best possible outcome would be averting violence while simultaneously demonstrating the power and authority of the loyal sentiment in Maryland.12

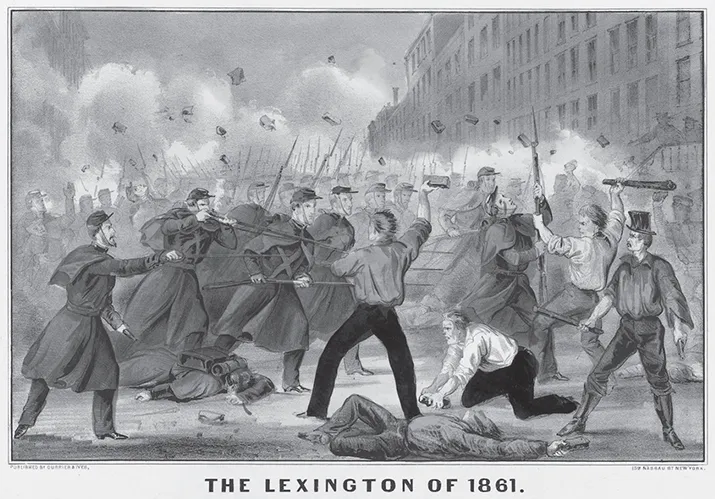

They were ultimately disappointed with the events in Baltimore the following day. The Union soldiers from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania arrived in Baltimore on April 19 and prepared to transfer railroad lines while in the city. Their cars were hitched to horses for the transfer through Baltimore. A mob formed around the cars on their journey, and as the crowd grew in number they were eventually forced to stop as cobblestone pieces crashed into the cars’ windows. The Sixth Massachusetts disembarked and was assaulted by the angry crowd hurling stones. Two shots were fired and the situation escalated with fist fighting. The Baltimoreans grabbed weapons from the soldiers and used them on the soldiers themselves. Once the riot died down, two Massachusetts soldiers were dead and dozens more wounded; twelve Baltimoreans lay dead on the streets.13

Reports of the activities in Baltimore recounted the frenzied state of the secessionist-leaning city. Colonel Edward F. Jones of the Sixth Massachusetts Militia authored his report of the events on April 22, 1861. He recalled the orders he personally gave his troops on the train to Baltimore on learning that they would likely face a resistant crowd. After distributing ammunition to his soldiers, Jones warned the troops of the opposition and challenge awaiting them: “You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and perhaps, assaulted to which you must pay no attention whatever, but march with your faces square to the front, and pay no attention to the mob, even if they throw stones, bricks, or other missiles.” He qualified this order by stating that “if you are fired upon and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire” and “select any man whom you may see aiming at you, and be sure you drop him.” Upon arriving, Jones reported that his men “were furiously attacked by a shower of missiles” and as they quickened their marching pace the increase in speed “seemed to infuriate the mob, as it evidently impressed the mob with the idea that the soldiers dared not fire or had no ammunition.” After pistol shots were fired into the crowd, the order to fire was given and “several of the mob fell” as the soldiers continued their trek through the streets of Baltimore. According to Jones, even the mayor armed himself with a musket, fired, and killed a man in his attempts to aid the Massachusetts men on their journey. Disgruntled over their fallen comrades and incensed by the continued assault, even aboard the departing train from the city, a soldier fired and killed a man who “threw a stone into the car.”14

The Baltimore Police Commissioners delivered their report to the Maryland General Assembly on May 3. The commissioners asserted that neither they nor anyone else in the city’s police department were made aware of the arriving federal troops until thirty minutes to an hour prior to their arrival. They also noted the controversial decision reached by the mayor, the governor, and the police to destroy bridges in order to prevent “further bodies of troops from the Eastern or Northern States” from passing through the city. The destruction of bridges further exacerbated Maryland’s tenuous position in the eyes of the federal government and elevated the need for Lincoln to gain control of the important buffer-zone state around the Union capital.15

Baltimore mayor George William Brown and Governor Hicks both quickly wrote to Lincoln following the riot. Mayor Brown informed Lincoln that a delegation was en route to Washington “to explain fully the fearful condition of affairs” in Baltimore. He continued by asserting that the citizens of his city were “exasperated to the highest degree by the passage of troops” and were “universally decided in the opinion that no more should be ordered to come.” He stated that the authorities did their best to protect Baltimoreans and the soldiers but their efforts were “in vain,” despite the fact that their actions prevented “a fearful slaughter.” As Brown concluded his letter, he took a more direct tone in his message to the president: “it is not possible for more soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every step.” After explicitly requesting that no more soldiers pass through Baltimore, he warned that if they did come through “the responsibility for the blood shed will not rest upon me.” Hicks appended a brief letter to Brown’s in which he endorsed the statements and requests made by the mayor and noted that he had been in Baltimore attempting to mitigate the situation.16

FIGURE 1.1. Rioting in Baltimore, April 19, 1861, by Currier & Ives (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

The following day Hicks penned a letter to Secretary of War Cameron in which he outlined the challenges he was facing in the secessionist stronghold city. He confessed that “the rebellious element had the control of things. They took possession of the armories, have the arms and ammunition.” Lincoln wrote Hicks the same day requesting his immediate presence along with the mayor of Baltimore in Washington to discuss issues “relative to preserving the peace of Maryland.” The Baltimore Riot and the need to control “the rebellious element” in Maryland moved to the forefront of the federal government’s consciousness within the first few weeks of the Civil War.17

The Baltimore Riot not only started speculation on Maryland’s loyalty; it was also often a point of contention for those who debated the state’s wartime position well into the t...