![]()

CHAPTER 1

Leather

The Deerskin Trade in the Southern Mountains

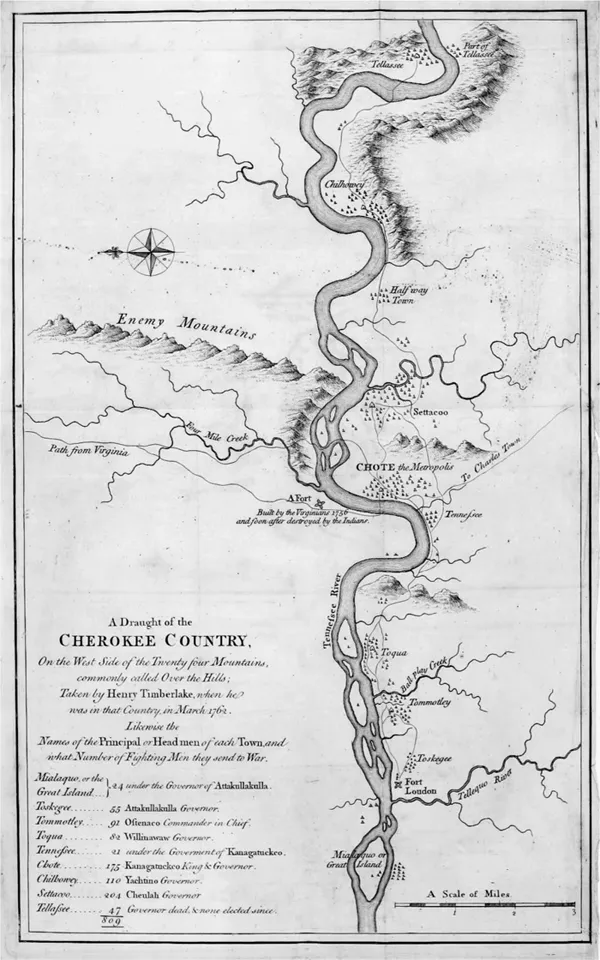

IN THE CLOSING DAYS OF 1761, Lieutenant Henry Timberlake noted in his journal that he had seen the ruins of Fort Loudon. Timberlake was in the mountains of what would become East Tennessee as part of a British delegation certifying that peace had been brokered with the Cherokee people, who had rebelled against their alliance with the British Empire in the French and Indian War. In addition to the fallen fort’s serving as a landmark, Timberlake viewed it as a reminder of the stakes of his party’s endeavor. The British had built Loudon five years earlier to guard the frontier from the French and their Shawnee allies, and a Cherokee war party had taken the fort only months earlier, killing part of its garrison. By the time Timberlake gazed upon the ruins of the fort, the relationship between the Cherokee people and the southern colonies had long been politically important to both parties, and just as significant was its commercial import. The colonial economies of South Carolina and Virginia, and to a lesser extent Georgia and North Carolina, had for decades relied on profits produced from the export of deerskins—many taken by Cherokee hunters—and peace offered the hope of renewing that trade. Timberlake believed that he and his fellow soldiers were ensuring a refreshed world of commerce rather than witnessing the end of an era.1

The Anglo-Cherokee War, as a part of the broader French and Indian War (itself one theater of the intercontinental conflict known as the Seven Years’ War), is well recorded, but its intimate connections with the century-old deerskin trade are less often highlighted. Historians frequently treat the commerce in hides in the southern mountains as a transient frontier enterprise, part of a hardscrabble economy only pursued before the arrival of more permanent farming, timbering, or mineral extraction. This interpretation does a disservice to the significance of the southern fur trade, which was an economic activity central to Indian life for nearly a century and did much to drive colonial understandings of the mountain frontier and eventually encourage Euro-American settlement in the region. Indeed, the exploitation of Appalachian resources undertaken in the deerskin trade would set a template for regional commercial exchange in the three centuries to follow. Appalachian environments—and the living creatures, like deer, that inhabited them—would do more to connect the southern mountains to surrounding places and cultures than to isolate them.

FIGURE 1.1. Henry Timberlake sketched a map of his journey through Cherokee Territory at the conclusion of the Anglo-Cherokee War. Note Fort Loudon in the lower right-hand corner. Henry Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake (London: J. Ridley, W. Nicoll, and C. Henderson, 1765).

The British constructed Fort Loudon at one center of this trade, close to the village of Tellico (one of the Cherokee Overhill towns) in the Little Tennessee River Valley near its junction with the Tennessee River. It was a location where people had lived, farmed, and hunted for perhaps ten thousand years when the first European traders arrived.2 Seen through English eyes it was a marginal place, on the far edges of their empire, but viewed from other vantages it was quite central. In the colonial era the Little Tennessee Valley existed at the intersection of English, French, and Spanish territorial interests and in an overlapping trade zone of the Virginia and Carolina colonies. To the north, across the shared and disputed hunting grounds of Kentucky, lay the powerful Shawnee towns and other peoples; to the south and west, Creek and Chickasaw people controlled the land. In short, southern Appalachia was an important crossroads, central to Cherokee people’s existence and significant to a great many other groups.

White-tailed deer themselves served as another focal point of colonial North America for roughly a hundred years, beginning in the late seventeenth century. As living creatures, possessing their own will, instincts, and learned behaviors, deer intersected with humans as part of ecosystems. But whitetails also became a part of a varied set of political economies, serving as an important resource for Cherokee villages as well as colonists from the Old World and ultimately fueling a global trade in deerskins. Eventually parts of deer bodies became commodities, as important for a time as any other trade good in the southeast. In the minds of many British officials and colonists, the leather made from white-tailed deer helped transform a marginal frontier place into an important region, a crossroads of commerce that would influence people and empires.

Historians have treated this deerskin trade in various ways. Older histories often approached this commerce through the lens of adventurous and independent fur traders, by consequence depicting it as a rustic, frontier activity, destined for displacement by more civilized endeavors. In short, it was part of a romantic but transient frontier, the sort of phenomenon that fit neatly into Frederick Jackson Turner’s theory of progressive American development. More recent histories have presented more nuanced takes, emphasizing the substantial economic importance of the trade for British, French, and Spanish colonies; exploring its devastating consequences for Native Americans, through the spread of disease, disruption of historic patterns of life, and alcoholism; and noting the intimate connections between the hide trade and warfare.3 A few scholars, Wilma Dunaway most notably, have labeled the deerskin trade a crucial component in the establishment and spread of a capitalist ethos in North America. Dunaway views the “southern deerskin trade as the key mechanism by which Native Americans and their lands were incorporated into the world-economy” and sees the pursuit of hides as “the chief instrument of economic expansion during the early Colonial period.” She likens the results to another version of a contemporary global phenomenon, that of the “putting-out system that destroyed traditional economic activities, generated dependency upon European trade goods, and stimulated debt peonage.”4 If equating the southeastern trade in whitetail hides to contemporary textile work in England is a bit specious, commerce in deerskins undeniably brought social, economic, and cultural revolutions to the southern mountains. The lives of Cherokee families, British colonists, European consumers, and millions of deer would be forever altered.

At the moment when Europeans first set foot in the New World, an incredible number of white-tailed deer inhabited much of North America. They had adapted to a wide range of habitats, from the tropical forests of Central America to the deciduous woodlands of Appalachia to the frigid coniferous forests of what would become eastern Canada. Only the largely treeless Great Plains and drier portions of the American West were entirely devoid of white-tails. Descriptions of their abundance are numerous and often include a note of wonder, as one from 1682, when Carolinian Thomas Ashe wrote, “There is such infinite Herds that the whole country seems but one continued [deer] park.”5 Attaching a precise figure to anecdotal accounts such as this is impossible, but historians and wildlife scientists have nonetheless attempted to calculate the contact period whitetail population. In the most exhaustive study to date, Thomas and Richard McCabe estimated the number of deer at “24 to 33 million,” and most other careful estimates fall within or close to their figures.6

These population numbers, if correct, reflect annual average populations more than a static continental herd of deer. Local populations then, as now, fluctuated widely, dependent on hunting pressure but also on a range of other environmental factors. For example, exceptionally hard winters, sustained drought, or lightning-sparked wildfires could cause regional or local populations to decline, while widespread tornado or hurricane damage, relatively common in the Southeast, could create additional edge habitats in mature forests, which could benefit local whitetail populations for a time.7 Deer in turn functioned as a sort of “disturbance” in many eastern forests, like those of the Appalachian Mountains. Dense deer populations over time created particular sorts of forests. As one ecologist has written, “White-tailed deer may therefore be considered a ‘keystone species’ in deciduous forests, because they have a disproportionately large impact on the distribution and abundance of other species in forest communities and the resulting community structure.” For example, whitetails favor white oak seedlings as browse, and their feeding suppresses that species, in turn “releasing” other trees, less-preferred ones such as sugar maples, to increase their stands. Over the span of decades, plentiful deer had the power to shape forests just as much as a hurricane or wildfire.8 Cumulatively, these varied processes led to shrinking and swelling deer populations, always fluctuating, never in balance.

White-tailed deer were among the most important natural resources for southeastern Native Americans. For many, including the Cherokee people, deer served as the primary animal food source, but whitetails provided more than just venison. Deer hides offered several advantages over the skins of other mammals: they were strong enough to stand up to hard wear yet supple enough to make comfortable clothing, and deerskin remained pliable when wet, unlike buffalo hide. As a consequence of these qualities and deer abundance, hides were used for a wide range of clothing and other goods. They became moccasins and gloves, arrow quivers, cordage, tobacco pouches, rugs, drumheads, and even the balls used in Cherokee games. In addition, white-tail bones, antlers, sinews, and hair had many uses, from tool handles to bow strings to insulation. Even the brains of the animal were used, to tan its own hide.9 These varied uses meant that Native Americans who relied on the species consumed a large number of whitetails each year, perhaps as many as nine or ten adult deer per person just for domestic use.10

Cherokee hunters took these deer in a number of ways. They pursued white-tails with bows and arrows, through the traditional means of solitary stalking or “still hunting” (waiting in ambush) (see fig. 1.2). But they, like other Native Americans throughout the whitetail’s range, also used communal methods of hunting, often involving fire. Intentionally set fires forced deer to move, often driving them toward a waiting group of hunters. These regular hunting fires in turn reshaped mountain environments, in many ways making them more suited to white-tailed deer. Regular burning of the woods suppressed the woody understory, created additional edge habitat, and fostered the growth of many herbaceous plant species favored by deer. Together Cherokee hunters, deer, and the frequent fires used in hunting formed distinctive woodlands throughout the southern mountains.11

FIGURE 1.2. An imaginative European depiction of southeastern Indians stalking deer. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1603. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Their reliance on whitetails meant that Cherokee people held a belief that deer were tied to more than just the state of Appalachian forests; they were a part of the very fabric of culture, society, and the spiritual world as well. Their mythology emphasized the importance of deer, weaving them into creation stories and explanations for the origins of illnesses. They told tales of how all deer once existed underground, to be released one by one from under a rock in times of hunger, but mischievous boys set them all free, populating the earth with game but necessitating hunting for meat. And Cherokee stories recounted how careful prayer to a deer’s spirit was necessary after a successful hunt, or else the spirit known as Little Deer would smite the hunter with chronic rheumatism, a crippling condition in a culture dependent on physical labor.12

Even as Cherokee hunting was drawn into networks of transatlantic trade during the eighteenth century, it remained freighted with a great deal of cultural and religious significance. Despite a growing dependence on the deerskin trade, there were cultural proscriptions against taking too much game and against extending hunting grounds too far, though these were not inviolable. Hunting trips could last as long as half a year, and hunters did not lightly undertake them. Preparation involved ritual abstinence and religious sacrifices, and symbols of the deer were everywhere: “seven deer skins folded” were part of the start of a hunt ceremony, as were divinations that might reveal “a great multitude of deers hornes” if the hunt was to be a successful one. During the hunt itself, deer tongues and spleens were sometimes offered as sacrifice, and hunters sat on deerskins in camp. Participation in the deerskin trade changed many things in Cherokee society—bringing economic intensification, pulling more members of society into the production of hides, and perhaps forming newly gendered divisions of labor—but it did not entirely eliminate the white-tail’s place in the older Cherokee cosmology.13

As important as deer were to Cherokee life, prior to the hide trade with Euro-Americans the animals were merely one part of an economy that relied on both wild and domesticated resources. Farming lay at the heart of Cherokee life, which revolved around seasonal work in fields of corn, beans, and squashes. Colonial English visitors to Cherokee towns in the late 1600s and early 1700s remarked on the fertility of mountain valley soils at sites like Tellico, which had “the richest soil, equal to manure itself, impossible in appearance ever to wear out.”14 Valley town sites typically lay within close reach of the diverse forest ecosystems of the mountain slopes, in a region that contained “all major forest complexes,” thanks primarily to varied exposures and elevation differences. These woods were rich in hickory nuts, acorns, chestnuts, black walnuts, and butternuts, as well as game, herbs, and edible roots, and the rivers and streams were home to a range of fish species.15 The Cherokee people’s ability to transform these natural resources into a relatively comfortable lifestyle impressed outside observers. One colonial traveler commented that a Cherokee hunter...