![]()

PART I

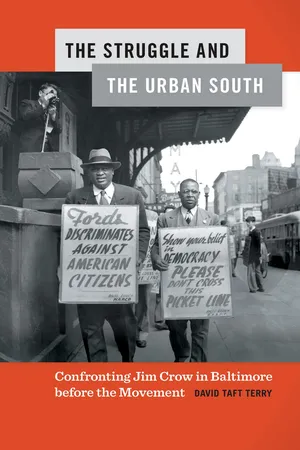

The rise of Jim Crow in Baltimore was met by a black commitment to struggle. Two key strategic characteristics would mark the struggle for nearly four decades thereafter. First, as Jim Crow was couched in the expansive false narratives of white supremacy—narratives that cast blacks as “lesser than,” with inherent cultural shortcomings, chronic intellectual incapacity, and broad moral insufficiency—blacks developed counter-narratives of independence, agency, and self-respect. The second characteristic of the black struggle that emerged through the first four decades of the twentieth century saw southern blacks establish regional and national intragroup alliances, particularly within the structures of nonpartisan social justice entities. National organizations moved to establish branches and commence work in the region, building a black nation of resistance.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Jim Crowed

Baltimore, 1890s–1910s

The Baltimore American ran a small headline on page six of its June 1, 1889, edition: “Thirty-Three New Lawyers.” The night before in Ford’s Opera House, the University of Maryland School of Law had held commencement. Though a violent rainstorm raged outside, “the night was not too bad for a good audience to be present.” Charles W. Johnson and Harry Sythe Cummings, third and tenth in the class respectively, stood among the graduates. Both men had completed the three-year program in only two years. Both men were black, and each had several well-wishers in the audience celebrating their achievement.

Days before the commencement, the community had fêted Johnson and Cummings at the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, with Everett J. Waring, the first black admitted to the bar in Baltimore, providing a keynote. “Let our young people have full and free access to … literary, industrial, and professional training,” he told those gathered, “[and] remove all hindrance to their entrance into any and all professions or callings and pursuits.” “Grant us this,” he said with assurance, “[and then] turn on the full blaze of the judgment and discriminations of this great age. … We cheerfully and confidently will abide the result.” Southern blacks in big cities like Baltimore were not afraid of the modernizing future. They embraced it. They pursued it.1

If back in 1887, when Johnson and Cummings first entered law school, their matriculation had met with at least mild protest, their subsequent overall experience had been one of inclusion, they argued—as “gentlemen associating with gentlemen.” Faculty and fellow students treated them without apparent racial prejudice, and this atmosphere continued through to the rainy graduation night at Ford’s. As a contemporary observer noted, “Good judgment and tact … prevented any color discrimination in seating the guests at the graduation exercises.” Before an audience of faculty, alumni, family, and friends—a gathering that included not only common folk, black and white, but also “some of the most aristocratic families of the South,” according to the New York Times—Cummings and Johnson were awarded their degrees without incident or special circumstance.2

In the fall of 1889, the semester after the graduation of Cummings and Johnson, two more blacks enrolled at the University of Maryland School of Law. One, John L. Dozier, had graduated from Johnson and Cummings’s alma mater, Lincoln College of Pennsylvania. The other new law student, W. Ashbie Hawkins, was an alumnus of Baltimore’s Centenary Biblical Institute (renamed Morgan College in 1890). They arrived at law school as prepared for its rigors as any other member of that first-year class. They also had reason to be encouraged about the prospects for a career after graduation, as both Johnson and Cummings were putting their degrees to appropriate use—together, for example, they had successfully defended a young black man falsely accused of assaulting a white girl, before an all-white jury, no less.

Quickly, however, things began to change at the law school—and in the city. Suddenly, it seemed, the ascendance of the likes of Johnson and Cummings represented a threat to the spaces and prerogatives of whiteness in Baltimore. White citizens raised the specter of “Negro domination” and began to demand statutory and other institutionalized restrictions on black opportunity. At the law school, this developed into a movement of white students and faculty alike who wanted not only for the university to cease admitting blacks but also for Dozier and Hawkins to be ousted before they finished the program. While both men ultimately finished their training at Howard University’s law school, nearly half a century would elapse before another of their color entered the University of Maryland.

Black Baltimoreans could feel their world changing around them. By the century’s close, whites had begun to curtail black access to public spaces or close them to blacks altogether. Things began to grow tighter, blatantly unequal, and more personal, with more derogatory language used to describe and address blacks. In the course of but a generation, to appropriate C. Vann Woodward’s famous phrasing, a comprehensive “capitulation to racism” had transpired. Jim Crow spread like a virus in the urban South, moving state to state, infecting education, housing, and employment. “The civil rights and privileges which the colored citizens have been enjoying for years have been gradually retrenched until now they are merely nominal,” the black press observed in 1890. Testament to the newness of these snubs was the apparent newsworthiness of their increasingly frequent incidence.3

Familiar public spaces, like parks and other places of outdoor recreation, became off-limits to blacks. A number of private concerns closed to blacks altogether, and those that continued to offer service (e.g., theaters, retailers, eateries) did so in separate and inferior ways or established dual pricing policies that charged black patrons a premium for the privilege of giving white businessmen their money. Even white Republicans—theretofore, since Emancipation, “friends of the Negro” whose gatherings in Baltimore had traditionally operated on the basis of interracialism—began to “Jim Crow” blacks to the balcony at party functions. By the 1890s in Baltimore, one of the South’s most populous cities, “prejudice … against Afro-Americans began at the street lemonade vendor,” one observer noted, “and like infinite series in mathematics continued without end.” Claiming to be “cast down but not dismayed,” Baltimore blacks were truly disappointed over being “Jim Crowed,” as they phrased it, and at “the great extent of the backsliding in moral conscience of the white people of Maryland.” No doubt searching for ways to salve wounded dignity, the black press editorialized that the moment offered “the opportunity of our lives,” the chance for blacks to react with unity, poise, and courage in meeting segregation’s challenge.4

In the eyes of black Americans and others, Jim Crow marked the whole of the South, as slavery had before, with a broad regional identity. This identity legally mandated white supremacy, and this was underpinned by narratives of anti-black racism. If there was nuance to urban blacks’ view, it perceived their capacity to resist Jim Crow in the South, marking their struggles in the South as functionally unlike those of their rural counterparts. Histories of Jim Crow must confront this. Blacks in the urban South—in communities like Baltimore—nurtured their capacities to resist in fundamentally different ways than did rural and small-town blacks. Consolidating their communities, they produced defiant counter-narratives to white supremacy, challenging the legitimacy of Jim Crow from the first moments of its rise at the end of the nineteenth century. These counter-narratives were executed in black professional and academic achievement, in entrepreneurial pursuits (large and small), and in their personal comportment. Indeed, from the “respectability politics” of strivers and elites to the demand from the lower and working classes for recognition of their personal dignity and self-respect, urban blacks in the South resisted the limiting presumptions of white citizens and authority figures alike, even at the cost of rebuke and sometimes physical violence. In the end, theirs proved to be an enduring black struggle for equality. Decades later, it inspired a civil rights movement, which demanded activism and the attention of broad segments of American life. For now, however, at the turn of the twentieth century, blacks struggled largely on their own.5

Building a More Human Life

At the start of the Jim Crow era, the Baltimore experience represented a broad historical framework of black urbanicity in the South. The ethos of urbanicity that had been an element of southern black vernacular consciousness since slavery continued to draw blacks to Baltimore and other cities in the region. As was the case in most of the urban South then, no central or single neighborhood of blacks existed in Baltimore. Both established and newly arriving black residents were spread in all quadrants of the city. Blacks constituted 10 percent or more of the total population in fifteen of the city’s twenty wards as late as 1880. They comprised no more than one-third of the residents of any single Baltimore ward, living in patchwork clusters across the city. If some residential blocks were all-black or all-white, many others were mixed—black and white living in close physical proximity.6

Annexation of land from Baltimore County, to the north and west of the city, nearly tripled Baltimore City’s size in 1888. Well-to-do whites moved farther from center city. What they left behind constituted the secondhand residences of an emerging black enclave. This development accommodated a consolidation of blacks. Blacks had lived in all parts of Baltimore before, but West Baltimore became prominent as a black enclave soon after the push and pull of emerging Jim Crow culture in the city. For decades West Baltimore received thousands of migrants annually—from the Maryland countryside, from the rural regions of other southern states, and even from other points within Baltimore itself.

Jim Crow descended with the rise of West Baltimore, and blacks met circumscription by building community, which became the key resource of resistance. To borrow Ronald Takaki’s useful description of American Chinatowns, West Baltimore early in the Jim Crow era promised to be for blacks “places where they could live a warmer, freer, and more human life among their relatives and friends than among [hostile] strangers.” Aspects of culture and identity that would be rebuked or received as threatening to empowered white prerogative elsewhere in the city could be expressed in these black spaces of the urban South without fear. For those blacks migrating to Baltimore from rural areas, a familiar southernness was discernable—an approach to urban life influenced by long-standing rural migration and inflected with rural sensibilities and mores. Tensions between black natives and black newcomers were evident, but high rates of in-migration to southern cities beginning in the late nineteenth century made newcomers ubiquitous. Quoting Angela Davis, Luther Adams has noted this quality of southernness as “Home” in his study of segregation-era blacks in Louisville. Early in the Jim Crow era, the southern black ethos of urbanicity nurtured an illusion that the black world was the whole world—that it could be made to sustain blacks and perhaps even allow them to thrive.7

West Baltimore’s rise as a black enclave came in stages, but these took place quickly. In little more than a generation, a fully diverse black population lived there: newcomers to the city (and even the state) and natives of Baltimore who had relocated across town to be where increasingly everyone wanted to be. Black households came to be tucked into the alleys and service ways along lower Pennsylvania Avenue and adjacent streets, which were some of the first to turn from white to black residency. From there they “push[ed] from the narrower streets to the wider ones,” according to historian Sherry Olson, “[moving] uphill, block by block.” Newcomers and natives from other parts of the city began to arrive, settling into clustered webs of structures that sat in the shadows of more substantial and fashionable homes. Some of the earliest West Baltimore arrivals were African American domestic workers employed by well-to-do whites. They lived in the neighborhood’s modest homes in smaller streets and alleys. Soon thereafter, with increasing flight of the white affluent population farther from center city, came a quiet arrival of Baltimore’s nebulous but emerging black middle class—service workers, teachers and other professionals, and strivers of all stripes. These took up occupancy, if not always ownership, of the neighborhood’s three-story row homes of exceptional quality. By the 1910s a great proportion of the “colored” schools’ faculties in the city lived amid the tree-lined splendor of upper Druid Hill Avenue and its fashionable cross streets. Soon working-class blacks too found the means to move deeper into West Baltimore, especially to the smaller streets but also along the grander streets where landlords divided some single-family homes into apartments for rent. Older neighborhoods around the city also attracted black migrants in sizeable numbers—Hughes Street District and Pigtown, for example—but these numbered far fewer than West Baltimore.8

Baltimore’s black population grew by 63.3 percent between 1880 and 1910. This population expansion outpaced the residential space available to blacks, however, and a harmful population density came to characterize West Baltimore. A typical neighborhood in this way was the 500 block of Biddle Alley. By the turn of the twentieth century, this single block contained fifty-six residences. The alley was cramped, spanning just twenty feet. By comparison, major streets nearby stretched at least three times as wide. Zoning was not in evidence, and six animal stables existed there, connected to carpenter shops, a firehouse, and blacksmithing shops. A 1907 study found only ten bathtubs on an entire similarly situated block: “One bathtub was evidently permanently devoted to the storage of old clothes, another served as a kitchen sink of a second-story apartment, a third had no water connection, and a fourth was used as a bed.” None had running water but instead accessed a hydrant in the courtyard, and “all used in common an exceedingly filthy and dilapidated privy with an overflowing vault.” Surface drainage oozed into the cellars of the homes. As worn-out and unhealthy environments of alleys and small streets spilled onto the main streets, blacks with the means to do so moved out along a northwest axis, expanding the black footprint of West Baltimore.9

Facing Jim Crow, Baltimore blacks built their institutions toward self-sufficiency and self-determination. Churches have long been acknowledged as symbolic and functional cornerstones of community development, but schools too were highly desired. Indeed, sometimes blacks perceived white educational privilege with great emotion. As a boy, for example, Baltimore native E. Franklin Frazier walked to school from his home on St. Paul Street, and his daily route took him past Johns Hopkins University (its original campus sat at the entrance to West Baltimore). Born in 1894 as segregation was beginning to remap the city, Frazier had come to realize that he would never enter Hopkins, no matter how well he did as a student. Hopkins would never allow him to compete with the best and brightest, because he was not white. As he walked, to get the distaste of frustration out of his mouth, he sometimes spat on the walls of the university as he passed them. Though it changed nothing about his material existence, he later recorded that he felt better, at least for the rest of his walk to school.10

Beyond their personal meanings to individuals, schools often functioned as markers of status, political clout, potential, and competence for the black community in the early Jim Crow urban South. Access to public education and control of it comprised an important signifier of urbanicity. Schools met present needs but were also foundations of resistance and possibility. From Emancipation through the end of the century, Bettye Thomas notes, “the education of black children remained the focal point of black protest in Baltimore.” On the whole, Baltimore’s public school system was inadequate for the masses. However, whites of means and ability did have access to educations at Baltimore Polytechnic High School, Baltimore City College (a high school), and Eastern and Western High Schools, which were more than adequate and offered college prep science and tech programs. But blacks, no matter their means and ability, were not afforded the opportunity to attend them—for no reason other than the color of their skin.11

The task of building scho...