![]() PART 1

PART 1

LEADERS![]()

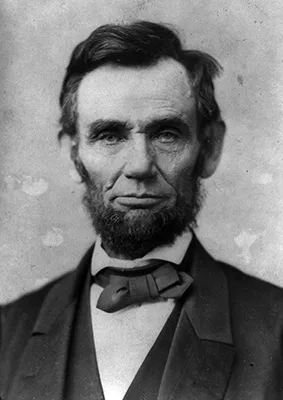

The “Gettysburg” Lincoln

The Back Story of a Full-Frontal Photograph

HAROLD HOLZER

I MUST ADMIT that I no longer remember exactly when I first cast eyes on what ultimately became, and remains, my favorite image of Abraham Lincoln: the intensely revealing, full-face, close-up photograph taken by Alexander Gardner in Washington on November 11, 1863.

For ages, I have thought it must have adorned the dust jacket of the very first Lincoln book I ever owned: Stefan Lorant’s Lincoln: A Picture Story of His Life. But no, I’ve recently been reminded that the photograph graced only the 1969 revised edition of Lorant’s iconic chronology of Lincoln portraits and not the 1957 version that I persuaded my younger sisters to purchase for me as a gift for my bar mitzvah—my thirteenth birthday—in 1962. Much as I treasure that first book, the Lorant original featured an 1861 photograph and not the 1863 image that took my breath away when I first studied it.1 So perhaps it was the 1969 edition after all, which I purchased for myself at age twenty, the moment it came out, and later brought to Lenox, Massachusetts, to get the author’s signature at our first meeting.

It was Lincoln’s strange gaze in the portrait that first fascinated me—the right eye a cool, intense gray, staring unblinkingly into the camera, but the left one roving upward in its socket, straying from the viewer for some unfathomable reason, perhaps a medical one, making the subject look mysterious, crafty, tragic, almost otherworldly. At our meeting, my hero Lorant told me he loved the picture, too, and then asked me to conduct a little experiment with him: take a strip of paper and cover half of Lincoln’s face at a time, from hairline to chin—and examine one half first, then the other. The startling result: two entirely different men. Viewed alone, Lincoln’s left side made him look bemused, his mouth curling into a smile, his eye rolling as if in dismay. Yet the right side showed a hard stare and a frown creasing his countenance. How can a man smile and frown simultaneously in the same photograph? Lorant and I conducted this demonstration, it might be noted, during the first days of the Marfan’s syndrome story, when two different medical experts grabbed headlines by contending that Abraham Lincoln had suffered from this debilitating genetic condition, whose symptoms included vertical strabismus—roving eye. But no, Lorant didn’t believe it. Lincoln was simply too physically strong to be a Marfan; just look at the wide shoulders and brawny arms in the Gardner photograph. How to explain it, then? Simple, Lorant replied: Lincoln had been kicked in the head by a horse as a child, and was, in his own words, “apparently [sic] killed for a time.”2 The concussed boy woke up eventually, but perhaps the injury had an atrophying effect, causing one side of the mouth to drop, one eye to lurch off heavenward.

From that day forward, I began studying the haunting picture more intensely. And what I have learned since at one level reaffirmed my affection for it. For here was Lincoln at the height of his powers, four months after the twin Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and only eight days before he would consecrate the former triumph with the greatest speech of his life, perhaps the greatest in American history. Here was Lincoln before physical decline set in, before the weight peeled off, the face sank, and the sockets under the eyes darkened into bottomless pools. I preferred this Lincoln— the man of astonishing strength—and not the one who slowly wasted away that the nation might live.

Ultimately, my obsession with the portrait inspired me to further research. Why was this particular picture made when it was, along with the companion images created at the same Gardner sitting? And why was the image so ubiquitous in the 1960s, yet apparently so rare in the 1860s? Not for years was I able to find the answers, and with them, to shed some light on the very nature of Civil War iconography—the work of artists in all media, who in fact depended on each other for sources and inspiration. Only then did it become clear: this image was not created by accident, in a void, or without a very specific and long-ignored purpose.

It is always important in studying and understanding early photographs to keep in mind that the experience of posing before the camera in the 1860s was neither casual nor candid. In the age long before official White House photographers, let alone the technologies that made possible anything other than stiffly posed formal exposures, celebrity subjects like Abraham Lincoln (or their advisors, along with the photographers who sought them out to sit) planned their gallery visits in advance, and carefully. Photographers who earned their living making portraits of their clients invited leading politicians, military figures, and theatrical celebrities to pose for them free. They then displayed their results in their waiting rooms to lure additional customers, and mass-produced copies for sale to Americans for their family photograph albums.

The celebrity sitters themselves were well aware of the rationale for their sittings, even the unfailingly modest Abraham Lincoln. In 1860, for example, he made sure to precede his career-altering Cooper Union address with a strategic visit to the New York City studio of Mathew Brady (Gardner’s future mentor and employer). The result was an extraordinarily influential portrait, widely reproduced in presidential campaign prints, banners, broadsides, and cartoons. While Lincoln at first dismissed the experience of posing by reverting to homespun informality—writing, “I was taken to one of the places where they get up such things, and I suppose they got my shaddow [sic], and can multiply copies indefinitely”—he later acknowledged, in the photographer’s presence, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President.”3

In other words, there were usually good political reasons for Lincoln to pose for pictures. As president, he did so often and for a purpose. The remark he addressed to Brady about the influence of the Cooper Union portrait, for example, was made when Lincoln sat for a series of pre-presidential photographs after he first arrived in Washington in late February 1861. The reason for his decision to sit that week seems obvious: he had just slipped into the capital through Baltimore in secret and, some whispered, in disguise, to avoid a rumored assassination plot. Cartoonists had a field day caricaturing the president-elect as a coward sneaking into the capital in a Scotch cap and military cloak, perhaps even Scottish kilt and a feathered tam.4 Lincoln desperately needed ameliorating, dignified images to supplant this comic assault—and Brady (with Gardner behind the lens) provided just the corrective portraits.

Although Lincoln went on to visit various Washington photographers repeatedly during his four years as president, he was usually invited to do so—by Gardner in August 1863, for example, to help him launch his own independent gallery. How, then, should we interpret a set of photographs made on November 11, 1863? The temptation, into which Stefan Lorant and others not surprisingly fell, was to suppose that the president decided that, in the same spirit that inspired him to Brady’s a few hours before he was to orate at Cooper Union three years earlier, the approach of his trip to deliver “a few appropriate remarks” at Gettysburg made mid-November the perfect time to “illustrate” his latest rhetorical effort: to sit for a portrait that would show the country what he looked like as he fulfilled this important assignment.5

Of course, this scenario assumes that Lincoln knew in advance that his Gettysburg Address would “live in the annals of the war,” as the Chicago Tribune later predicted, or that the president would in fact devise such a words-and-image strategy on his own.6 Alas, as I eventually discovered, he did not. Journalist Noah Brooks was one of those eyewitnesses to the sitting who inadvertently led later observers astray. Brooks did admit that Lincoln had chosen the date of his Gardner visit coincidentally—“it chanced to be the Sunday before the dedication of the national cemetery at Gettysburg,” Brooks wrote, because “Mr. Lincoln carefully explained that he could not go on any other day without interfering with the public business and the photographer’s business, to say nothing of his ability to be hindered by curiosity-seekers ‘and other seekers’ on the way thither.” But the Gettysburg association animated Brooks’s recollection anyway because the journalist vividly recalled that moments after they left the White House for Gardner’s Seventh Street gallery, “The President suddenly remembered that he needed a paper, and, after hurrying back to his office, soon rejoined me with a long envelop [sic] in his hand in which he said was an advanced copy of Edward Everett’s address to be delivered at the Gettysburg dedication…. In the picture which the President gave me, the envelope containing Mr. Everett’s oration is seen on the table.”7

Brooks was onto something. Everett had dispatched a preview copy of the long oration he planned for Gettysburg so the president could review it before writing his own brief remarks. Everett thought Lincoln would not want inadvertently to repeat the messages he had reserved for himself. Indeed, the envelope can be seen on Gardner’s prop table in a few of the poses made that day, although it appears that Lincoln never bothered to open it and peruse its contents while he waited for the photographer to reset his plates between poses. Still, Gettysburg seemed to be on everyone’s mind that day. Brooks asked Lincoln if he had finished his own speech. Not yet, the president replied, but it would be brief—“short, short, short,” as he put it.8

Yet the resulting portraits were not “Gettysburg” photographs—much as subsequent generations wanted them to serve as such, especially after the twentieth-century discovery of a shot made from a distance at the actual November 19 ceremonies, in which the blurred figure of a seated Lincoln, head cast downwards, was barely visible. But if the powerful full-faced portrait I’ve admired for so long was meant to show his countrymen the way the great man looked on the eve of his dedicatory address, why was it so difficult for his admirers to find copies of the pose at the time it was taken: late 1863? Gardner always mass-produced and widely distributed his latest Lincoln photographs, but not this one. And Lincoln cooperatively posed for Washington’s cameramen not to provide prints for his own family album, but to supply fresh poses his admirers could collect for their own. Brady, Gardner, and the others fortunate enough to woo the president to their galleries invariably issued the results in carte de visite form, the rage of the day, and produced thousands of copies for general sale to the public.

Here lay a major problem with the Gettysburg “illustration” theory. What may be the finest of all wartime camera portraits of Abraham Lincoln remained virtually unseen in carte de visite format—and was hardly seen by the public at all—until one A. T. Rice, who later assumed control of the Gardner archive, issued copies in time for the Lincoln centennial in 1909. This was the greatest Lincoln photo never seen. Why, then, did the exquisite poses of November 11 never make it into the hands of these ready pre– and post–Gettysburg Address customers? Why was “my” superb portrait, in a way, wasted?

A notation made by another eyewitness to the sitting provided the elusive clue. Lincoln’s private secretaries, John G. Nicolay and John Hay, were also on the scene at Gardner’s that autumn Sunday. Someone among the party—perhaps Lincoln, maybe Gardner, but most likely the staffers—persuaded Lincoln into a rare group pose. “Nico and I immortalized ourselves by having ourselves done in a group with the Presdt.,” Hay recorded in his diary. But what he said a few sentences earlier proved the smoking gun. “Went with Mrs Ames to Gardner’s gallery & were soon joined by Nico & the Prest. We had a great many pictures taken. Some of the Presdt. the best I have ever seen.”9

Here, albeit in shorthand, was the explanation my hero Lorant—not to mention pioneer photo historian Frederick Hill Meserve before him, and more recently the outstanding authority Lloyd Ostendorf—had all somehow missed. On November 11, 1863, Lincoln arrived at the Gardner gallery with Nicolay and Brooks. But Hay had gotten there earlier with a “Mrs. Ames” and waited there for the president to arrive. Who was the mystery woman? Hay never explained (his was a diary he never intended to publish, after all), but she is absolutely key to why the photographs were made in the first place and why they were not widely released in the second place. And her presence may also help explain why so many of the Gardner poses that day turned out to be some of “the best” John Hay had ever seen. For she was an artist, and when artists witnessed Lincoln’s sessions with photographers, as they did on at least three other occasions before and after November 11, 1863, the results tended to be superior to what the photographers could create on their own.

Sarah Fisher Clampitt Ames (1817–1901) was also an antislavery activist, a wartime nurse in the temporary hospital established in the U.S. Capitol, and the wife of the well-known portrait painter Joseph Ames. So Lincoln, ever grateful to such politically sympathetic volunteers, would have been inclined to cooperate with her. More to the point, she was also what the early historian of Lincoln portra...