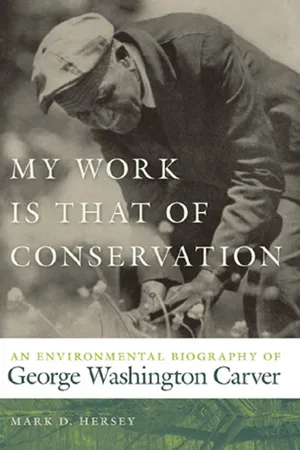

My Work Is That of Conservation

An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

My Work Is That of Conservation

An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver

About this book

George Washington Carver (ca. 1864–1943) is at once one of the most familiar and misunderstood figures in American history. In My Work Is That of Conservation, Mark D. Hersey reveals the life and work of this fascinating man who is widely—and reductively—known as the African American scientist who developed a wide variety of uses for the peanut.

Carver had a truly prolific career dedicated to studying the ways in which people ought to interact with the natural world, yet much of his work has been largely forgotten. Hersey rectifies this by tracing the evolution of Carver's agricultural and environmental thought starting with his childhood in Missouri and Kansas and his education at the Iowa Agricultural College. Carver's environmental vision came into focus when he moved to the Tuskegee Institute in Macon County, Alabama, where his sensibilities and training collided with the denuded agrosystems, deep poverty, and institutional racism of the Black Belt. It was there that Carver realized his most profound agricultural thinking, as his efforts to improve the lot of the area's poorest farmers forced him to adjust his conception of scientific agriculture.

Hersey shows that in the hands of pioneers like Carver, Progressive Era agronomy was actually considerably "greener" than is often thought today. My Work Is That of Conservation uses Carver's life story to explore aspects of southern environmental history and to place this important scientist within the early conservation movement.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

NOTES

Prologue

Chapter 1. Were It Not for His Dusky Skin

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: Macon County, Alabama, 1896

- One: Were It Not for His Dusky Skin

- Two: The Earnest Student of Nature

- Three: The Ruthless Hand of Mr. Carenot

- Four: In a Strange Land and among a Strange People

- Five: Teaching the Beauties of Nature

- Six: Hints and Suggestions to Farmers

- Seven: The Peanut Man

- Eight: Divine Inspiration

- Nine: Where the Soil Is Wasted

- Epilogue: My Work Is That of Conservation

- Notes

- Index