![]()

CHAPTER 1

The U.S. Constitution and Federalism

Constitutions are important because they establish the basic rules of the game for many political systems. They specify the authority of government, distribute power among institutions and participants in the political system, and establish fundamental procedures for conducting public business and protecting rights. Just as drawing up or changing the rules can affect the outcome of a game, individuals and groups battle over constitutions, which can help determine who wins or loses politically.

When the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1789, federalism was one of its most important elements. Federalism is a type of political system that gives certain powers to the national government, others to the states, and some to both levels of government. In addition to the United States, countries such as Australia, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland have federal systems. These differ from unitary systems such as those of Great Britain or France, where all authority rests with the national government, which can distribute it to local or regional governments. Federalism also contrasts with confederations, where all power is in the hands of the individual states, and the national government has only as much power as the states give to it. The United States used such a system during 1781–1788 under the Articles of Confederation, as did the Confederate States of America. During the 1990s, confederations were tried following the break-up of the national governments in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

The U.S. federal system is not static; in fact, it has changed significantly over the years. Four key factors have had a major influence on the way federalism in the United States has developed: national supremacy, the Tenth Amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment (all three found in the U.S. Constitution), and state constitutions (covered in part 2).

National Supremacy

The U.S. Constitution’s stability is due in large part to its broad grants of power and its reinterpretation in response to changing conditions. Article 1, Section 8 grants Congress a series of enumerated powers such as taxing, spending, declaring war, and regulating interstate commerce. It also permits Congress to do whatever is “necessary and proper” to exercise those enumerated powers. This language is referred to as the elastic clause because of its flexible grant of authority. Article 6 reinforces the power of the national government by declaring that the Constitution and federal law are “the supreme law of the land.” This supremacy clause thus identifies the U.S. Constitution as the ultimate authority whenever there is a need to resolve a dispute between the national government and the states.

In an 1819 case, McCulloch v. Maryland, the U.S. Supreme Court adopted a broad view of the national government’s powers when it decided that the elastic clause allows Congress to exercise implied powers that are not mentioned explicitly in the U.S. Constitution but that can be inferred from the enumerated powers. The supremacy clause and implied powers have been cornerstones for the expansion of the national government’s powers. Congress occasionally has turned programs over to states, as it did with changes in welfare laws during the 1990s, and has imposed new requirements and costs on them, as it did under the No Child Left Behind Act adopted in 2002 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act adopted in 2010.

The Tenth Amendment

The constitutions, laws, and policies of the states cannot contradict the U.S. Constitution. Thus, federalism allows states many opportunities to develop in their own way, but it always holds out the possibility that the federal government may act to promote national uniformity. Much of the debate over ratification of the U.S. Constitution focused on claims that the national government would be too powerful. This concern was reflected in proposals to add twelve amendments in 1789. Ten of the proposed changes were ratified by the states in 1791 and are commonly referred to as the Bill of Rights. The Tenth Amendment reads:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

The amendment thus grants states reserved powers, but it does not define them. As one might expect, this has produced conflicts between the national and state governments, many of which have ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court. For much of the period from the 1890s through the mid-1930s, the Court restricted efforts by Congress to enhance the power of the federal government. Since then, the power of the national government has grown, although some recent court cases have favored the states.

The Fourteenth Amendment

In 1868, the national government’s power over the states was strengthened by the addition of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. One of three amendments designed to end slavery and grant rights to blacks after the Civil War, the Fourteenth states in part:

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This language is a fundamental statement of the principle of dual citizenship: Americans are citizens of both the nation and their state, and they are governed by the constitutions of both governments. The U.S. Constitution guarantees minimum rights to citizens that may not be violated by the states. The states, however, may grant their citizens broader rights than are guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

The Fourteenth Amendment has had an interesting and controversial history. The U.S. Supreme Court generally has defined the amendment’s somewhat vague guarantees in terms of other provisions found in the U.S. Constitution. Since 1925, the Court has employed a process known as selective incorporation, which incorporates into the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment the protections offered by the Bill of Rights. It does this by applying these guarantees to the states on a selective (case-by-case) basis. Congress, too, has used the Fourteenth Amendment in support of laws that restrict the power of state and local governments.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

State Constitutions

States adopt their constitutions within the context of national supremacy; enumerated, implied, and reserved powers; dual citizenship; and the provisions of the Tenth and Fourteenth Amendments. Many state constitutions are modeled after the U.S. Constitution. State constitutions generally do not include implied powers. States also possess police power, namely, the ability to promote public health, safety, morals, or general welfare. The police power is among the “reserved powers” in the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. States often delegate police powers to local governments.

Basic Differences in State Constitutions

Most state constitutions are extremely long, in contrast to the 8,700 words in the original U.S. Constitution. Major reasons for such lengthy constitutions are numerous amendments, extended sections about local governments, and the absence of implied powers. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, which has been amended only twenty-seven times, state constitutions are amended frequently. This often is done to make policy changes that would seem easier to bring about by passing a law. For instance, Georgia voters had to approve an amendment in 1992 to remove language in the state constitution that prevented creation of the Georgia lottery. Putting policies in constitutions makes it harder for opponents to change them, however. Alabama’s constitution is the longest among the states because it includes numerous local amendments that cover only one county.

The absence of implied powers means that state constitutions tend to be more detailed and restrictive in defining the powers of government. In addition, the U.S. Constitution says nothing about local governments, which state constitutions often cover at great length.

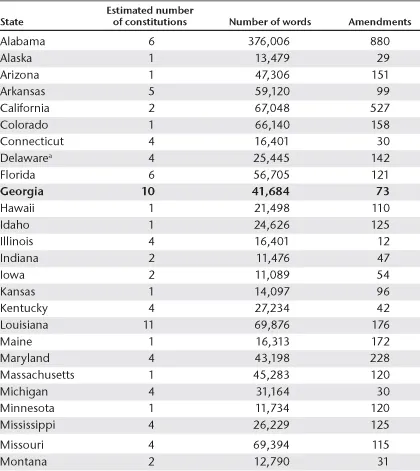

TABLE 1

State constitutions as of January 1, 2010

Table 1 indicates the number of constitutions each state has had, as well as the length of the state’s current constitution and the number of its amendments. Georgia is noteworthy in two ways. First, it has had ten constitutions; only Louisiana has had more. Second, Georgia’s current constitution took effect in 1983, making it very new. Only Rhode Island can be considered “younger,” following a major revision of its 1842 constitution in 1986.

Amending State Constitutions

PROCEDURES IN THE STATES

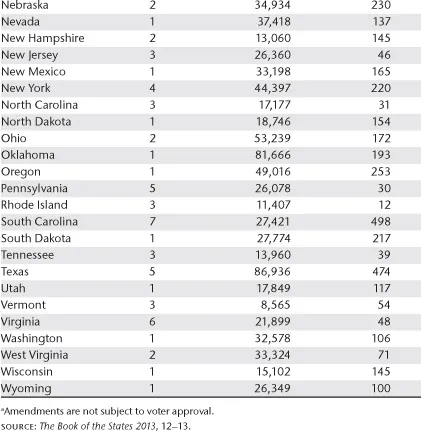

The states use various methods to amend their constitutions (see table 2). Unlike amendments to the U.S. Constitution, every state but Delaware requires voters to approve constitutional amendments. To submit a proposed amendment to voters, eighteen states require a simple majority of their legislators to vote in favor of doing so. Most states are more restrictive. Georgia is among the twenty-one states requiring two-thirds of its legislature to vote in favor of submitting a proposed amendment to its constitution. Some states impose the obstacle of getting an amendment approved in two different legislative sessions before it can be submitted to voters. Four states, but not Georgia, limit the number of amendments submitted to the voters at one election.

TABLE 2

Procedures for amending state constitutions

Forty-two states require that a simple majority of voters must vote yes on an amendment for it to be ratified. The other states use several alternatives. Two states require more than a simple majority, two-thirds in New Hampshire, for example, and three-fifths in Florida. A few states, such as New Mexico, require a simple majority to ratify most amendments but larger majorities to ratify certain types of amendments. Five states require approval by a majority of those voting in an election, not just those voting on the amendment. Thus, if people vote on highly visible offices such as governor but skip an amendment on the ballot, not voting on the amendment is the same as voting “no.” Similarly, in Nebraska, those casting a “yes” ballot must be a majority on the amendment and thirty-five percent of the total voting in the election.

During 2012, 135 constitutional amendments were proposed across thirty-five states. Eighteen of the proposals were put on the ballot through the citizen initiative process. Of the 135 proposals, 92 were adopted (68 percent). Thirty of the proposed amendments dealt with government finance, taxation, and debt. Another 20 dealt with their state’s bill of rights.1

AMENDING THE GEORGIA CONSTITUTION

The Georgia legislature can ask the state’s voters to create a convention to amend or replace the Constitution. The General Assembly also can propose amendments if they are approved by a two-thirds vote in each chamber of the legislature--a procedure like that at the national level. The governor has no formal role in this process but may be influential in recommending amendments and mobilizing public opinion before voters go to the polls. Georgia is not among the eighteen states whose constitutions allow amendments through the initiative process, in which citizens circulate petitions to place proposed amendments on the ballot for voters to ratify or reject in a statewide referendum.

The U.S. Constitution requires ratification of amendments by legislatures or conventions in three-fourths of the states. In contrast, the Georgia Constitution requires ratification by a majority of the voters casting ballots on the proposed amendment. Such proposals are voted upon in the next statewide general election after being submitted to the electorate by the General Assembly (November of even-numbered years).

![]()

CHAPTER 3

Constitutional Development in Georgia

Replacing any state’s constitution is a rare event. Amending a constitution is much more common. Both types of change, however, have produced long and often complicated documents. Efforts to amend constitutions, like those to replace them, are often linked to politics. This is true of Georgia’s ten constitutions, each of which reflects a political response to some conflict, problem, or crisis.

Politics and State Constitutions

Unlike the U.S. Constitution, most state constitutions include a wide range of very specific policies. Of course, legislatures normally enact policies by passing laws. Why clutter up state constitutions rather than limiting them to more fundamental issues? Three reasons stand out: attempts to gain political advantage, responses to state court decisions, and efforts to meet the requirements of the national government. Georgia’s constitution includes numerous examples of all three.

POLITICAL ADVANTAGE

Many policies in state constitutions result from efforts by groups to gain a strategic advantage over their political opponents. If a group can get its position on an issue written into a state’s constitution, changing that policy becomes much more difficult. This takes advantage of the rules of the game by forcing the opposition in the future to pass its own amendment rather than simply enacting a law. Amendments adding policies to Georgia’s constitution have included earmarking, tax breaks, issues of morality, and limits on decision making.

Like many state constitutions, Georgia’s includes earmarks, requirements that revenues from certain sources be spent for designated purposes. Needless to say, earmarks can benefit specific interests. The most significant are motor fuel taxes, which Article 3 requires to be spent “for all activities incident to providing and maintaining an adequate system of public roads and bridges” and for grants to counties. Moreover, this money goes for these purposes “regardless of whether the General Assembly enacts a general appropriations Act.”1 Thus, the Constitution provides those interested in highway...